Hanford overview

Lea la historia de Hanford en español aquí.

The past, present, and future of the Hanford Site is long and complex, dating back well before the site's construction in the 1940s and long into the future beyond today's cleanup efforts.

During the World War II and Cold War years, the site's focus was on plutonium production. Now, efforts are geared at cleanup of one of the most contaminated nuclear sites in the world.

Explore the story of Hanford below.

An overview of the Hanford Site's history, largely from the 1940s to the late 1980s.

The site today

Since the signing of the Tri-Party Agreement in 1989 between our agency, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), we work with the EPA to ensure Energy — Hanford's owner and manager — follows environmental laws and meets cleanup deadlines stipulated in the Tri-Party Agreement governing Hanford cleanup.

Ecology also communicates with the Nez Perce Tribe, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, and the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation to hear their perspectives and goals for Hanford cleanup.

Cleanup projects today are complex and bountiful. While much has been achieved in the 30-plus years of cleanup so far, countless challenges and dangers remain. Our priority is to oversee cleanup of the Hanford Site and ensure the protection of the area's land, air, and water for current and future generations.

Highlighted below are just some of the site's most important facilities or cleanup projects and their current status. Is there a part of Hanford not described below you'd like to learn more about? Let us know.

Hanford's K-West Reactor, one of three reactors not yet cocooned, and the cocooned D Reactor.

Nine nuclear reactors were built on the Hanford Site during World War II and the Cold War to produce plutonium for the nation's nuclear weapons program.

The world's first full-scale plutonium production reactor, B Reactor, began operations in September 1944, followed soon by the other eight reactors in the following two decades. All of the reactors were shut down between 1965 and 1987, with N Reactor being the last.

So far, seven of Hanford's nine reactors have been cocooned as part of ongoing cleanup efforts. Cocooning, also known as being placed in interim safe storage, involves removing all of a reactor's supporting facilities that surround it and sealing up the reactor itself.

Each cocooned reactor is entered every five years for inspection to ensure nothing is getting in, and no contamination is getting out. Cocooning lasts for 75 years, and allows radiation levels to decay to a safer level for future dismantling and disposal.

The B, K-East, and K-West Reactors are the only ones to have not yet been cocooned. Work is ongoing at the K-East and K-West Reactors prior to cocooning, and B Reactor has become a Manhattan Project National Historical Park location.

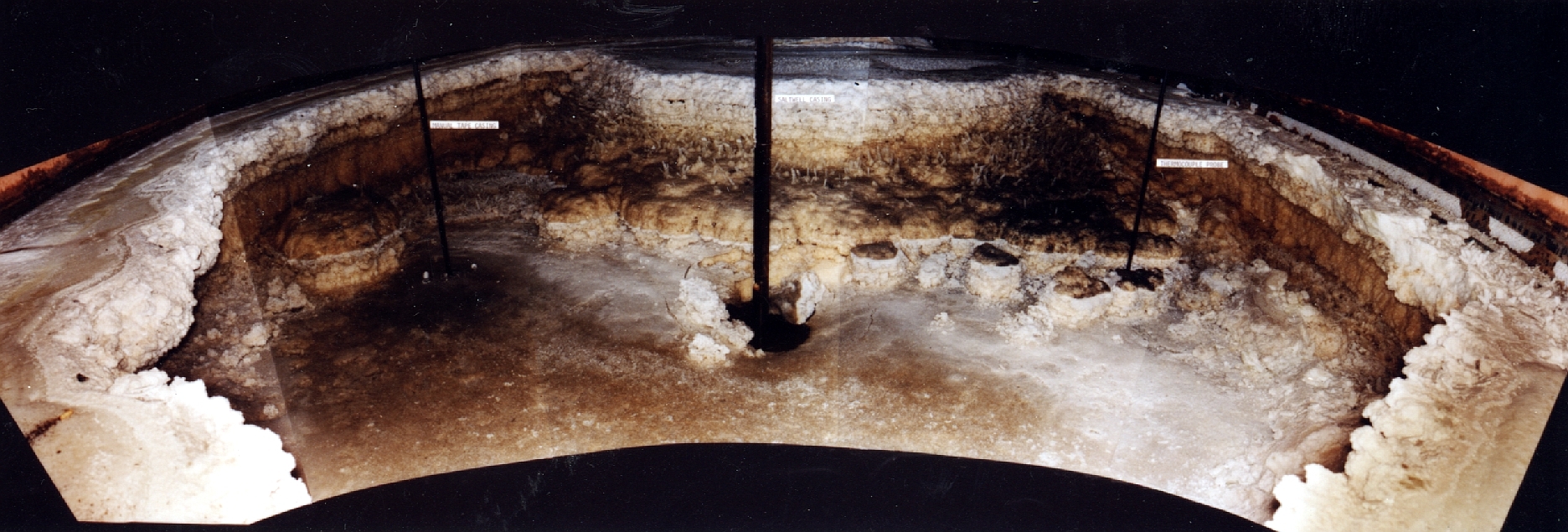

A look at the toxic, radioactive waste inside one of Hanford's 177 deteriorating underground storage tanks.

Today, there are 177 underground storage tanks on the Hanford Site, holding about 56 million gallons of highly radioactive and chemically hazardous waste – the byproduct of decades of plutonium production.

The tanks range in storage capacity from 55,000 gallons to more than one million. Of the 177 tanks, 149 are single-shell and 28 are double-shell.

All of the tanks are well past their design life of about 25 years, and at least 67 are assumed to have leaked in the past, and three are currently leaking. More than one million gallons have leaked from the tanks.

If waste remains in the tanks, untreated, it will eventually enter the ground, groundwater, and Columbia River. One of our top priorities is to ensure the safe handling and retrieval of Hanford tank waste and see that it's sent to the Waste Treatment Plant.

Read more about the Hanford tanks on our tank waste monitoring and closure page.

Read more about leaking tanks.

A look at Hanford's Pretreatment Facility, part of the Waste Treatment Plant.

Our agency oversees the permitting, construction, and eventual operation of the Waste Treatment Plant, which will treat Hanford's underground tank waste. The plant's been under construction since 2002, and has faced numerous delays.

At the plant, tank waste will undergo vitrification — the transformation of a substance into a glass. Through the Waste Treatment Plant's various facilities, the tank waste will be separated into high-level waste and low-activity waste streams before combining with glass-forming additives.

The vitrified waste will then be placed into stainless steel containers for eventual storage and disposal. While the treated waste will still be radioactive, it'll be in a more stable form and won't seep into or pollute the air, water, and soil.

Treament on low-activity waste is expected to begin in 2023. Read more about the plant and vitrifiction on our Waste Treatment Plant page.

Hanford's Plutonium Finishing Plant before and after demolition phase. (Images courtesy U.S. Department of Energy)

One of Hanford's most highly contaminated facilities was the Plutonium Finishing Plant (PFP), also known as Z-Plant. PFP operated from 1949 to 1989 and was the end of the line for plutonium production at the Hanford Site.

PFP was a complex of more than 60 buildings on the Hanford Site. Irradiated fuel rods from Hanford’s nine nuclear reactors were processed elsewhere on site to extract plutonium in liquid form – plutonium nitrate. At PFP, that liquid was processed into hockey puck-sized “buttons” that were then sent to nuclear weapons production facilities elsewhere in the country. That work left PFP’s two central processing facilities among the most contaminated buildings at Hanford.

Open air demolition began in 2016, and in summer 2017, plutonium and americium contamination was detected outside the work zone, and work briefly stopped. Demolition resumed and in December 2017, when PFP's Plutonium Reclamation Facility was knocked down to its foundation, there was a widespread release of plutonium and americium.

We joined with the EPA to issue a stop work order prohibiting further demolition. We worked with Energy to ensure it developed adequate protections and more rigorous safety protocols.

From 2018 to 2019, work gradually resumed in phases from lower-risk tasks to full demolition again. In early 2020 the demolition phase was finished. Work concluded in November 2021.

You can read more about PFP's demolition and updates on our PFP status page.

Hanford's five processing canyons.

Five massive facilities on the Hanford Site were responsible for removing plutonium from fuel rods during production years, and remain highly contaminated today.

The "canyons," named for their hundreds of feet in length and dozens in height, include: B Plant, T Plant, U Plant, Plutonium Uranium Extraction Plant (PUREX), and Reduction-Oxidation Plant (REDOX).

Of the five, one of the most recognizable is PUREX. This canyon was built in the 1950s, began operations in 1956, and eventually shut down for good in 1988. Two tunnels extend out from the complex and house highly contaminated rail cars, along with other highly-contaminated equipment.

PUREX made the news in May 2017, when a portion of the roof of PUREX Storage Tunnel 1 collapsed. We issued an order to Energy to ensure both Tunnel 1 and Tunnel 2 were stablized to minimize the danger of further collapses.

Throughout the rest of 2017, workers stabilized Tunnel 1 by pumping in engineered grout to encase and cover the highly radioactive materials stored in the tunnel. Eventually, after the public had a chance to comment, we allowed Energy to grout Tunnel 2, too.

Another of Hanford's canyons, T Plant, is the oldest nuclear facility in the country still operating with a current mission, although its current mission is quite different than it was decades ago. Today, T Plant is a decontamination and repair facility where workers treat, verify, and repackage radioactive and hazardous waste. Gases trapped in drums of waste are also sampled.

Highly radioactive sludge from the K West Reactor fuel storage basin is also being temporarily stored at T Plant.

Ultimately, plans are to decontaminate and demolish each canyon.

A view of Hanford's 300 Area, taken in September 2015. (Photo courtesy: USDOE)

A worker stands next to the 324 Building's B-Cell. (Photo courtesy: USDOE)

Hanford's 324 Building in January 2020.

Hanford's 324 Building in January 2020.

300 Area

Hanford's 300 Area is the part of the site closest to the city of Richland, and also adjacent to the Columbia River.

The area included fuel manufacturing operations during plutonium production years, as well as experimental and laboratory facilities. Fuel manufacturing operations during production years saw raw uranium brought into the 300 Area to be manufactured into fuel rods for Hanford's nine plutonium production reactors.

Cleanup of the 300 Area entails the decommissioning, deactivation, decontamination, and demolition of hundreds of buildings and facilities. A lot has been accomplished so far, but significant work remains, such as cleanup of numerous solid waste burial grounds and the 324 Building, among other work.

During production years, workers disposed of a variety of dangerous and highly contaminated waste in these burial grounds with little regard to environmental protection or public safety, leaving workers today the dangerous, complicated task of uncovering exactly what was dumped into these burial grounds and cleaning up the waste.

324 Building

The Chemical Materials Engineering Laboratory, more commonly known as the 324 Building, is one of the last major facilities yet to be demolished in the 300 Area.

Parts of the building are highly contaminated and include a number of both radiological and non-radiological laboratories, administrative areas, and other support facilities.

Demolition and cleanup of the 324 Building, already a dangerous and complex task, was made more difficult after a breach in the area below the B-Cell was discovered, revealing highly radioactive contamination in the soil beneath the facility.

A number of contamination incidents have happened during cleanup so far. However, our agency will continue to monitor the site and take any necessary action.

324 Building

The Chemical Materials Engineering Laboratory, more commonly known as the 324 Building, is one of the last major facilities yet to be demolished in the 300 Area.

Parts of the building are highly contaminated and include a number of both radiological and non-radiological laboratories, administrative areas, and other support facilities.

Demolition and cleanup of the 324 Building, already a dangerous and complex task, was made more difficult after a breach in the area below the B-Cell was discovered, revealing highly radioactive contamination in the soil beneath the facility.

A number of contamination incidents have happened during cleanup so far. However, our agency will continue to monitor the site and take any necessary action.

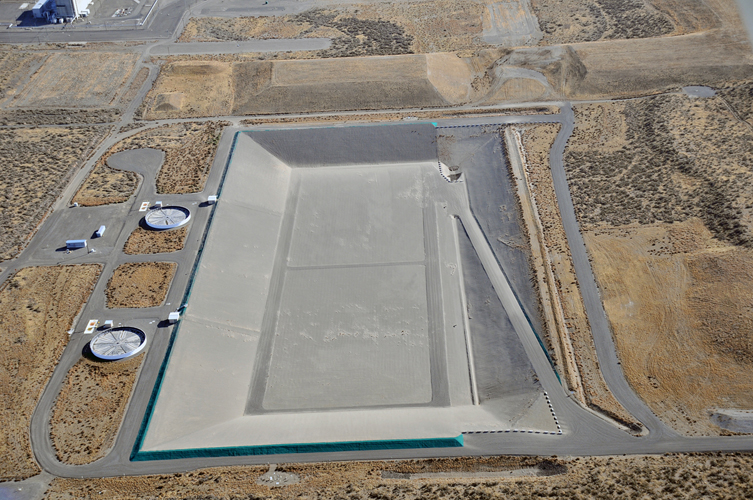

Hanford's Integrated Disposal Facility. (Photo courtesy: USDOE)

Hanford's Environmental Restoration Disposal Facility. (Photo courtesy: USDOE)

ERDF

Hanford's massive landfill, known as the the Environmental Restoration Disposal Facility (ERDF), is located in Hanford's 200 area and was originally constructed in 1996. Since being built, ERDF has seen four major expansions, most recently in 2011. The landfill is regulated by the EPA.

ERDF accepts only Hanford waste including low-level radioactive, hazardous, and mixed wastes. Today the landfill has taken in more than 18 million tons of waste and has a capacity of about 20 million tons.

IDF

The Integrated Disposal Facility (IDF) is another landfill located near the center of the Hanford Site. IDF has a much smaller capacity, about one million cubic meters, and currently has two disposal cells. IDF hasn't accepted waste yet.

Both ERDF and IDF are built in such a way to catch liquids not meant to be stored at the landfills, which are then treated and returned to the soil. The two facilities can be expanded if needed.

The 200 West Groundwater Pump and Treat System.

To treat the billions of gallons of contaminated groundwater throughout the Hanford Site, six groundwater pump and treat facilities were built. Operations began in the 1990s.

The facilities remove various contaminants such as cesium, strontium, hexavalent chromium, tritium, carbon tetrachloride, and more. To date, the pump and treat facilities have treated several billion gallons of groundwater.

Five of the pump and treat stations are located in the 100 area of the Hanford Site near the D, DR, H, K-West, and K-East Reactors. The sixth is in the 200 West Area on Hanford's central plateau, and is the largest.

The 200 West Groundwater Pump and Treat System has the ability to treat up to 2,500 gallons of water per minute. The pump and treat systems are fed by extraction wells throughout the Hanford Site. Treated water is injected back into the ground.

For more information on groundwater treatment, check out the U.S. Department of Energy's annual soil and groundwater reports.

Deer stand in front of Hanford's cocooned D Reactor.

Of the 586 square miles making up the Hanford Site, only a small portion of that was used for plutonium production. The rest acted as a security and safety buffer, thereby leaving many areas virtually untouched.

A main area of focus in the present day is maintaining and protecting the land, water, and wildlife throughout the Hanford Site. Part of the cleanup mission is also to restore impacted areas.

One such area not used for plutonium production is the Arid Lands Ecology Reserve, the only remaining sizeable shrub-steppe ecosystem in Washington state. This swath of land is located between the northeast-facing portion of Rattlesnake Mountain and State Highway 240.

The Arid Lands Ecology Reserve is managed by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory for Energy.

In addition to the reserve, the Hanford Site also features the largest fall Chinook salmon spawning area in the Columbia River system; the longest free-flowing stretch of the Columbia River above Bonneville Damn; Gable Mountain; and many sites with unique and irreplaceable historic, cultural, and scientific heritage.

Read more about restoring and preserving Hanford's natural resources on our natural resources protection page.

Interactive Hanford map

On the map below you can explore the Hanford Site and select individual facilities or areas for more information.

An interactive map of the Hanford Site. You can zoom in and select individual areas of the site.

Contact information

Ryan Miller

Communications Manager

Ryan.Miller@ecy.wa.gov

509-537-2228