Tank waste monitoring and closure

Hanford's 149 single-shell and 28 double-shell tanks store the site's most dangerous waste. One of our top priorities is to ensure the safe handling and retrieval of Hanford tank waste and see that it's sent to the Waste Treatment Plant. The waste will be incorporated into glass and stored in steel canisters for safe, stable, long-term disposal.

The most dangerous waste

Hanford's underground storage tanks hold the most dangerous waste created over four decades of plutonium production in Washington. All of these tanks are well past their design life of about 25 years. At least 68 tanks are assumed to have leaked in the past, and three are leaking at this time. An estimated 56 million gallons of mixed hazardous and radioactive waste remain.

If waste were to remain in the tanks, untreated, it would eventually enter the ground, groundwater, and Columbia River. The U.S. Dept. of Energy's Environmental Impact Statement projected that the river could be severely affected if that waste were to reach the river without any further action.

Of the 177 tanks, the 149 oldest have just a single shell between their contents and the environment. These tanks do not comply with Washington law, which requires that all underground storage tanks have a secondary container. Single-shell tanks pose a greater risk to develop new leaks.

In the late 1980s to mid-90s, much of the liquid was removed in hopes of making them more stable and reducing the risk of leaks. The remaining waste is similar to the consistency of saltcake (crystallized salt structures), wet concrete, or sand.

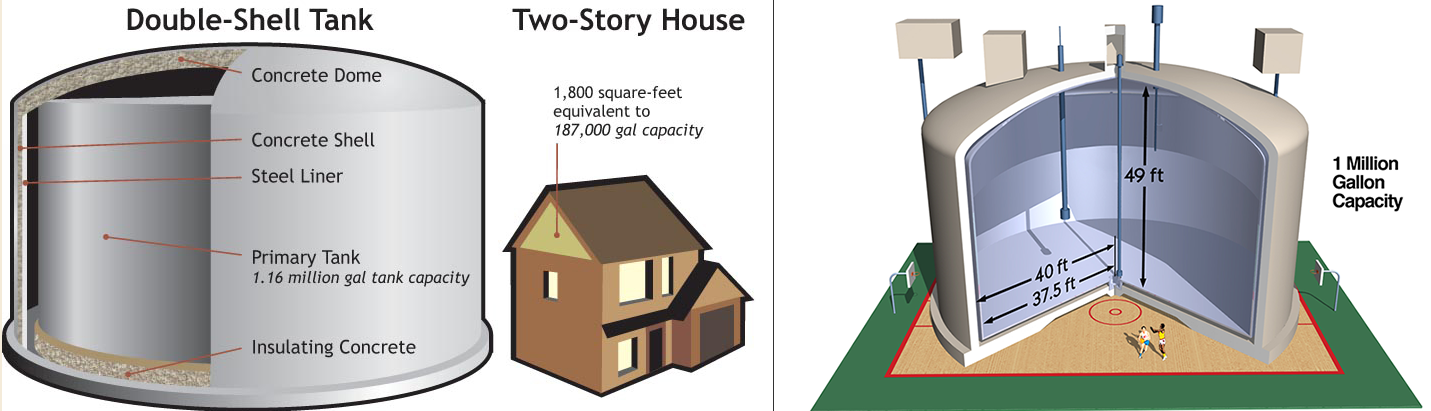

Twenty-eight tanks have double shells. Unfortunately, in 2014 the oldest double-shell tank (AY-102) developed a leak from its inner tank to the outer tank.

US DOE declared the tank unfit for use and will submit a closure plan for the Hanford Sitewide Rev 9A permit.

The remaining 27 tanks remain operating and comply with state law, but also are well past design life. Waste is being transferred from the single-shells to the double-shells for eventual movement to the Waste Treatment Plant.

Handling millions of gallons of dangerous waste

Hanford's massive underground tanks range in capacity from 55,000 gallons to more than a million gallons. To build them, workers cleared out large flat depressions, then erected the tanks in groups called "tank farms." The tanks were then surrounded with soil, leaving the tops of the tanks about 7-10 feet below ground to provide shielding from radiation.

Pipes, called risers, provide access into the tanks. While some risers are larger, some are only a foot in diameter, and none were designed to make it easy to empty the tanks.

Although much of the liquid has been removed, it's nearly impossible to get all of the liquid out without emptying the tank. Think of it as trying to remove the water from a hole at the beach — you can scoop the water out but it seeps back through the sand.

Why is waste so hard to remove from the tanks?

Tank waste retrieval is extremely difficult, both technically and physically. Because of the limited access — not to mention the radioactive and toxic environment — retrieval equipment inside the tank must be operated using video monitors and remote equipment. The hostile conditions damage and wear out electronics and other equipment. As equipment is removed and replaced, workers must use extreme care to avoid exposure to chemical and radioactive waste. In addition, multiple pipes and rods obstruct access within the tank, creating physical barriers to waste removal equipment. Tanks are considered clean when no more than 360 cubic feet of waste remain — or less, depending on tank size.

As waste retrieval progresses, the waste from single-shell tanks is sent to double-shell tanks through a system of hose-in-hose transfer lines. As the waste is moved, it's run through an evaporator to remove excess water.

Eventually, waste will be transferred from the double-shell tanks to the Waste Treatment Plant to be encapsulated in glass through a process known as vitrification.

Meanwhile, tanks are continuously monitored to ensure that none are currently leaking. Monitoring occurs both in-tank, by measuring volume, and in the surrounding soil using moisture and radiation detectors.

What is the status of the Hanford tanks?

Our goal for cleaning up tank farms is to make sure the tanks are closed as safely as possible and preventative measures are taken to minimize environmental impacts from waste already in the soil, waste remaining in the tanks, or waste that may be leaking from the tanks.

To make closure decisions, we need information about existing soil contamination, possible remedies, and the effects of waste that may remain in the soil and tanks after we finish cleaning up as much as possible. Closing Hanford's single-shell tanks gets very complicated with the abundance of regulations and work activities needed.

Periodically, we publish Hanford tanks status updates.

Related links

Contact information

Jeffery Lyon

Tank Waste Storage, Operations and Closure

Hanford@ecy.wa.gov

509-372-7950