East Pritchard Park on Bainbridge Island was a NRDA restoration project.

There’s big news in Port Angeles this month. The Western Harbor group has signed agreements to settle their Natural Resource Damages. The money will go toward environmental restoration projects. But what are Natural Resource Damages?

Natural Resource Damage Assessments

When a person or organization lets toxic substances into the environment, they have to pay for the cleanup. Toxic site cleanup is focused on protecting humans and the environment from exposure to toxic substances. That's what Washington's cleanup law, the Model Toxics Control Act, instructs and allows us to do. But sometimes that toxic contamination has already harmed the environment. In that case, the polluter may be liable not just for cleaning up the mess, but for restoring the environment they hurt. That's where the Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) process comes in (we pronounce it “nerd-uh”).

Oysters are one of the many natural resources sensitive to contamination.

Like in a civil lawsuit, the ‘victim’ is awarded compensation, called ‘damages.’ In this case, the victim is the environment. Since the environment can’t represent itself, a trustee council is made up of representatives from state, federal, and tribal governments. The trustee council assesses the damage and presents a claim to the people or organizations responsible for the damage — Potentially Liable Persons, or PLPs. Then the PLPs work or pay to restore habitat to make up for the loss and support future natural resources like fish, shellfish, and birds.

In Port Angeles, the trustee council is made of representatives from the Lower Elwha Klallam, the Jamestown S’Klallam, and the Port Gamble S’Klallam tribes, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Ecology. They are working on two separate NRDA agreements. The agreement that was just reached was for the Western Harbor area, and is open for public comment until April 26. The PLPs for that area are known as the Western Port Angeles Harbor Group. The details of the agreement with Rayonier, the PLP responsible for contamination on the other side of the harbor, are still being worked out, so they aren’t public yet.

Successfully completing the NRDA process settles the PLPs’ liability for the effects of the contamination. The Trustees can’t sue them over the same lost natural resources in the future, unless they contaminate the area again. The PLPs are still liable for cleaning up the contamination, if they haven’t already.

How do you judge the value of what was lost?

It’s hard to put a number on environmental loss. The council has to answer three big questions:

- What would the area have been like without the contamination?

- How much have the resources been affected by the contamination?

- For how long have they been affected by the contamination?

A peek at the past

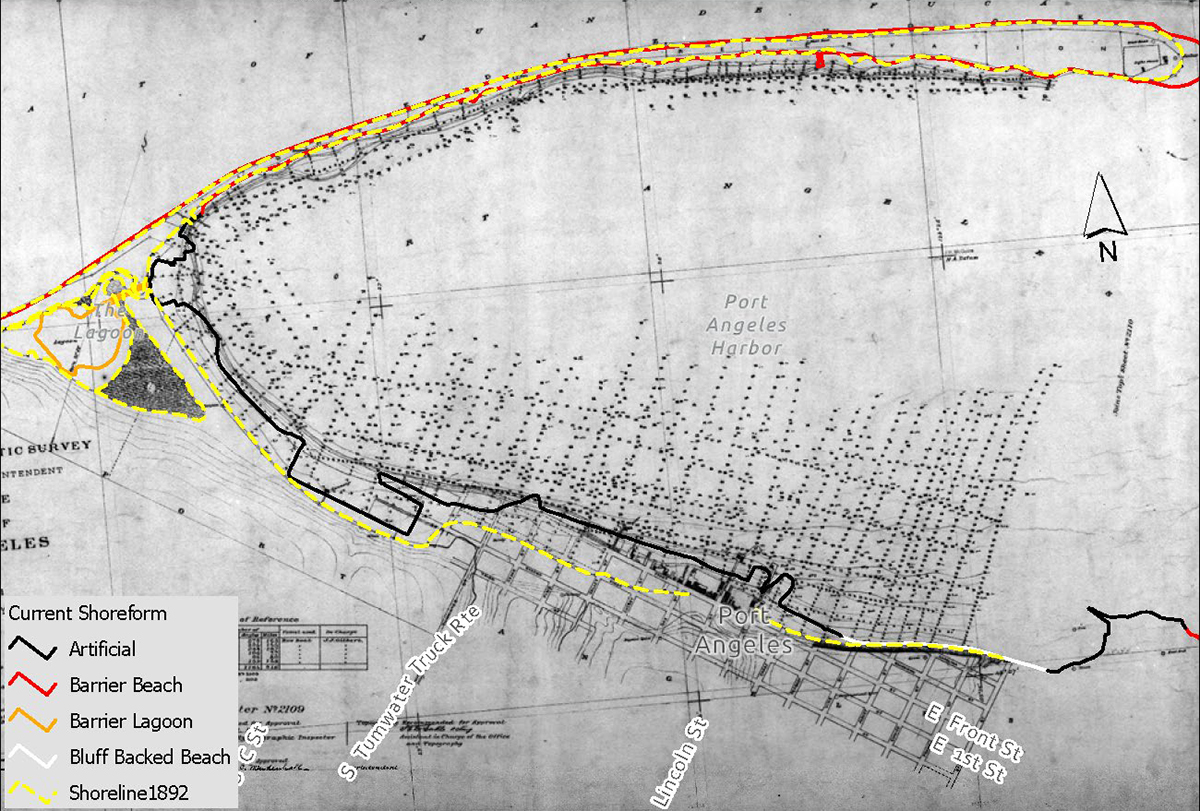

First, the trustee council has to figure out what the area would be like without contamination. They look at historical documents, maps, and data, talk to local tribes, and look at similar areas that don’t have contamination. If a tribe used to be able to live on the shellfish from a bay, and now there are almost no shellfish in a bay, it’s clear that bay has been hurt. Either the shellfish were hurt directly, or harm to the bay habitat made it hard for them to survive. NRDA only applies to harm from contamination, not shoreline development, changing water levels, or any of the other things that can hurt a fragile system. The trustee council uses information on the contaminants to tease out how much of the damage was likely due to toxic pollution.

A 1982 map with the modern shoreline traced over it shows the change in the harbor over the last 100 years

Assessing the present

Next, the council has to evaluate what’s there now: Are the fish gone, or sick, or are there fewer of them? How is the contamination affecting the fish and other life?

A lot of the data comes from studies that were already done as part of cleanup work. If more studies are needed for a good assessment, the PLPs have to pay for them.

Damage over time

To be fair to the people and environment, NRDA takes into account how long the environment has been hurt. If the effects of toxic pollutions started twenty years ago, that’s twenty years’ worth of fresh fish or healthy clams people were missing out on!

Coming to an agreement

A NRDA settlement comes from an agreement between the Trustee Council and the PLPs. That agreement lays out the environmental restoration work the PLPs will do, or the money the PLPs will pay. If the PLPs don’t agree, the Trustee Council may present the claim in court for a judge to decide.

Choosing restoration projects

The Trustee Council and the PLPs first look for ways to restore habitat in the area that was injured, in a way that will help the resources that were hurt: fish, shellfish, birds, or other critters. If the contamination hurt salmon, then the restored habitat should help salmon. The restoration doesn’t have to be the same kind of habitat, though: the goal is equal habitat value. For instance, there’s a lot of deep water habitat, but marshy shorelines are in short supply and are really helpful for a lot of critters, so it’s usually more valuable to restore shorelines and estuaries.

The trustees can also look at it as a dollar amount. They put a dollar amount on what was lost, and build new habitat that costs that much.

It depends what kind of restoration opportunities are in the area. The Trustee Council and the PLPs have to agree to a project or group of projects that they think is fair ‘payment’ to compensate for the harm to the environment.

“Cashing out” and leaving it to the Trustee Council

Planting native plants is a common part of restoration work.

Sometimes there isn’t a good restoration opportunity in the area that was contaminated, or the PLPs would rather not manage the restoration themselves. Maybe the area is entirely industrial, or cleanup construction is going to take years before any restoration projects could begin. In that case, the PLPs can settle with the Trustee Council for a dollar amount. Then the PLP’s part is done. That’s what is happening with the Western Port Angeles Harbor Group. The Trustees and the Western Harbor group couldn’t find a set of restoration projects that they agreed would make up for the harm done, and rather than spend more time looking, they agreed to a cash-out deal.

The Trustee Council will take that money and look for ‘high value’ restoration projects: things that will really make a difference. That means they look for projects that are important to the environment and the community. That might mean restoring:

- An area that’s vital for fish, like estuary or beach habitat.

- An area with particularly rare or sensitive habitat.

- An area that connects two pieces of good habitat: big stretches of habitat are much more helpful to wildlife than several separate pieces, even if the total area is the same.

- An area that gives the public more access to a resource — like shoreline access for clamming.

Port Angeles harbor has protected beaches that are rare in the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

The trustee council also tries to keep the money in the community. For instance, if the Port Angeles Trustee Council can’t find a restoration opportunity in Port Angeles harbor, they’ll try to find a project that’s in the Port Angeles area and benefits the city, community and local tribes by helping species that use the harbor. First they’ll look at the harbor itself, though. Port Angeles harbor has habitat that’s both rare in the area and important for sea life: the protected harbor beaches and lagoon.

Documenting it all in the DARP (Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan)

Once the Trustee Council and the PLPs come to an agreement, they release two documents for feedback from the public: A Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan (DARP) and a settlement agreement, called a consent decree, or sometimes multiple consent decrees.

- The DARP is a document that explains the plan for restoration or payment, and all the information that went into the decision. It includes the data and analysis about the site, the possible projects the Trustee Council and PLPs considered, and their eventual decision.

- The consent decree is the legal document that settles the PLPs’ liability for natural resource damage. Like with a cleanup, there can be multiple PLPs. How they divide the cost between them is their business.

A NRDA consent decree does NOT settle the PLPs’ liability for cleaning up the contamination that caused the harm. That’s a different process.

The discussions are private until an agreement is reached. Then that agreement is shared with the public through these two documents. The trustee council runs a public comment period to get feedback before they are finalized. The DARP and consent decree can be changed based on what the public have to say.

Successful restoration projects

A NRDA helped to restore the Qwuloot Estuary, on the Snohomish river near Marysville. A levee there was breached in 2016, letting tidewaters back in to two creeks and giving young salmon a protected place to forage and grow. A settlement is about to be finalized that will create a gently sloping beach and tidal area in the otherwise-industrial heart of Seattle, right at the mouth of the Duwamish River. And in Everett, the giant Blue Heron Slough project will open up yet more habitat for birds and young fish.

All in all, more than 990 acres have been restored or are being restored by the NRDA process in Washington State, and an additional 389 acres have been protected. That’s over 1,040 football fields, or more than two square miles, of improved and protected lands.

The Qwuloolt estuary.