In June 1881, the first steam engine from the Northern Pacific Railroad chugged down the line into the town of Spokane Falls, Washington Territory, population 594. Named after the falls that carved through narrow canyons of basalt bedrock, this town would eventually become a crossroads where three transcontinental railroads met.

Now the state’s second largest city, you can’t tell the story of Spokane Falls — reincorporated in 1891 as “Spokane” after an 1889 fire razed its former downtown — without the railroads.

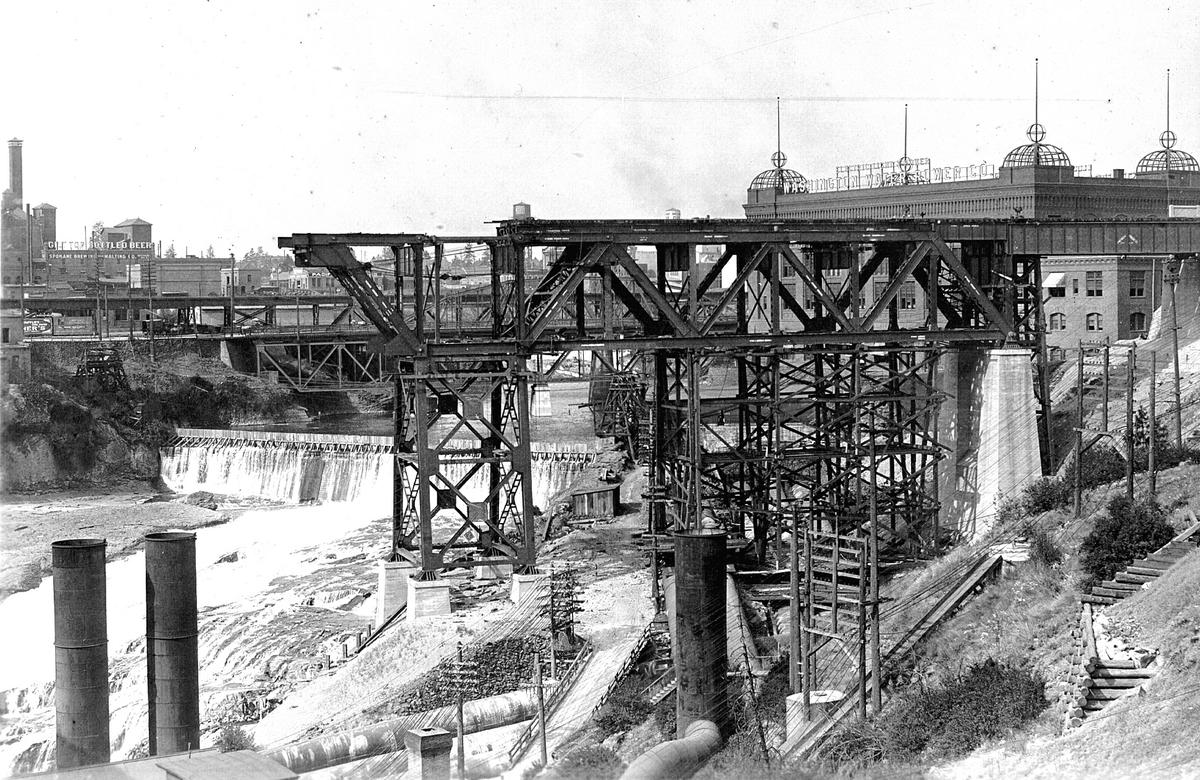

As the railroad boom began, competing companies raced to lay track and connect to the area’s resources, including newly discovered silver mines in northern Idaho. The Spokane Valley’s complicated terrain would require many bridges, elevated tracks, and trestles crisscrossing the Spokane River.

The Union Pacific train station in 1913, being built on the former site of Spokane's city hall. Courtesy: The Spokesman-Review.

As a demonstration of the railroad’s clout in the early 20th Century, the Union Pacific Railroad decided to build a large train depot in downtown Spokane. To accommodate it, Union Pacific convinced the city council to demolish and move their own city hall building. All this to make way for a new passenger rail station, which opened in 1914, dominating the southern bank of the Spokane River with a massive 8-track elevated trestle and platform.

The Union Pacific trestle being built across the Spokane River in 1913, connecting to the West Spokane Yard. Courtesy: The Spokesman-Review.

On the opposite bank, on a bluff above the river’s northern edge, Union Pacific connected to an 80-acre railyard and steam engine maintenance facility commonly known as the West Spokane Yard. With miles of tracks, a roundhouse, a steam locomotive repair and passenger car servicing complex, fuel storage and refueling facilities, Union Pacific’s West Spokane Yard supported millions of dollars of commerce and thousands of passengers along their journey across America.

Though the railroads were still going strong, by the 1950s the age of the steam locomotive was proverbially running out of steam. A rapid shift began toward diesel locomotives that were cheaper and safer to operate. It also allowed longer trains that operated at a higher capacity. Constrained by the river and surrounding neighborhoods, the West Spokane Yard just couldn’t accommodate the necessary growth.

After Union Pacific purchased 205 diesel locomotives and spent nearly $3 million to build a new rail yard a few miles away, it finally abandoned the West Spokane Yard in 1955. Rail traffic shifted away from the north bank of the river to the newly consolidated rail yards and realigned tracks on the south bank.

The legacy of the steam era

Courtesy: Washington State Historical Society.

Steam engines, though they invoke nostalgic industrial visions of a bygone era, were by no means a clean technology. In the early 20th century, coal was the primary fuel used to heat the boilers of steam engines. When Union Pacific’s steam locomotives needed maintenance in the Spokane area, they were taken to the West Spokane Yard.

Removing contaminated material from an ash trench at Kendall Yards.

The process of cleaning and servicing a locomotive involved scraping out and disposing of the coal ash and clinker that built up inside the firebox. Coal ash is high in cancer-causing (carcinogenic) compounds including carcinogenic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (cPAHs) and heavy metals that don’t burn off. At the West Spokane Yard, this ash was buried on-site and was distributed in several areas — often in trenches dozens of feet deep — leaving tons of material that contaminated the surrounding soil and later would have to be excavated and removed.

Near the mid-20th century, many railroads had shifted and even retrofitted former coal- and wood-fired locomotives to a cheap new fuel oil called “Bunker C.” At room temperature this thick, sticky, viscous fuel is not what most people would think of as oil. This tar-like fuel is what remains after lighter, more “useful” fuels such as diesel and kerosene are extracted from crude oil. It has to be heated just to flow enough to be used.

The West Spokane Yard housed and dispensed large quantities of Bunker C oil. Pipes and tanks that held the fuel often spilled and leaked into the surrounding soil. Because the fuel was cheap, the leaks weren’t much of a concern to the railroad. And this fuel, that most assumed couldn’t move through the soil due to its thick nature, accumulated in the soil over the decades — in some locations leaching down 30 feet deep.

Metal plating operations and repair and maintenance of the old steam locomotives also left lead, cadmium, and arsenic in the soil, adding further damage to the environment. For nearly 60 years after Union Pacific abandoned the West Spokane Yard, this prime property overlooking the Spokane River sat vacant and unused.

In 1974, the World’s Fair came to Spokane, and the city’s civic and business leaders worked hard to revitalize and transform blighted industrial properties along the river into parks and trails with spectacular views of Spokane Falls. Many abandoned properties along the river were cleaned, replanted, and restored. The Union Pacific Station and its elevated platform was demolished. But the old West Spokane Yard did not benefit from this flurry of economic and environmental activity. It would remain vacant.

Under the state's environmental definitions, the railyard was identified as a “brownfield” — an unused property with possible environmental contamination. While this brownfield designation acknowledged the potential issues that lie ahead, it also came with economic opportunities and grant funding for potential redevelopment. The Washington Department of Commerce, City of Spokane, and Ecology all worked together to help redevelop this property, using loan funds from Commerce’s Revolving Loan Fund.

The making of Kendall Yards

The beginnings of what we now know as Kendall Yards came in fits and starts. In 1990, a company took interest in the abandoned railyard and purchased the property for potential redevelopment. However, the extent of contamination on the property was not fully known. Once site investigations began, it was discovered that the soil surrounding the old refueling lines and massive oil holding tanks was contaminated with Bunker C and several trenches filled with coal ash were documented.

Downtown Spokane is just across the river from the railyard site.

But by 2004, the company that kicked off the development had gone bankrupt. Another developer, Marshall Chesrown, bought the property the following year and rebranded it as “Kendall Yards.” He pitched it as a high-end development with upscale housing, retail, and over a million square feet of commercial space. More importantly, Chesrown went full steam ahead with a promise to completely clean up the property. Working with the EPA Brownfields program and Ecology’s Voluntary Cleanup Program, Chesrown proposed to clean the property to an “unrestricted use” level for future residential development. Clean enough for parks and housing without any environmental restrictions.

Excavation of a bunker C area.

By 2006, the cleanup was completed. In less than one year, more than 200,000 tons of contaminated soil was removed from the site, including cadmium, lead, and arsenic. Both Ecology and EPA were satisfied with the cleanup and the project was given a letter of “No Further Action.” The project was removed from the state’s Hazardous Sites List after taking comments from the public in April 2006.

But even then, the project wasn’t safe. The economic shocks at the start of the Great Recession in 2007–2008 again derailed the project, forcing it into bankruptcy and uncertainty. This failure was cheered by some, as critics had panned Chesrown’s expensive vision of high-end real estate next to a lower-income neighborhood as an unnecessary gentrification of the area.

Once again, the project was revived, but the final iteration of Kendall Yards was toned down to a more modest proposal. With the environmental contamination already addressed, and with an improving economy, Kendall Yards was finally given the green light to start development in 2010. The project was once again full-steam ahead. Building quickly commenced and the first housing units went on the market by 2012.

Kendall Yards is now a vibrant addition to Spokane, with quaint shops, restaurants, public art, housing and condos, all in a walkable setting with spectacular views of the river below.

Throughout 2020, we’re marking our agency’s 50th anniversary with stories on how Washington state’s commitment to environmental protection has developed, and the results that commitment has achieved.