“Future risks of climate change depend on decisions made today. As scientific understanding of the pace, scale, and drivers of climate change improves, governmental decision-making must adapt to new information.”

Those were Gov. Jay Inslee's words last December as he directed Ecology to develop a new rule that will ensure that the potential emissions from major new projects in our state are consistently and comprehensively evaluated, and identify how those impacts can be mitigated.

This week, Ecology kicked off that rulemaking process, with a goal of adopting the new regulations by September 2021. We’re calling this the “Greenhouse Gas Assessment for Projects” rule — “GAP” for short.

Counting the emissions from a new project might sound simple on the surface, but there are a lot of complex details and issues that go into an accurate analysis. When industry uses natural gas and oil as fuels or as ingredients to make other products, how do you consider the emissions that come from drilling wells, pumping the petroleum out of the ground, putting it into a pipeline, and shipping it to the factory or facility? And how do you consider emissions tied to uses downstream from the facility?

Why is this important? Washington faces serious challenges in the years ahead from climate change. Washington depends on snowpack for water supplies and irrigation — and that snowpack is shrinking. Wildfires have caused huge damage to communities — and smoke from those fires has exacted an even higher toll on peoples' health. Rising sea levels threaten coastlines, and acidifying oceans will impact the environment, and industries that depend on those environments, like shellfish farming.

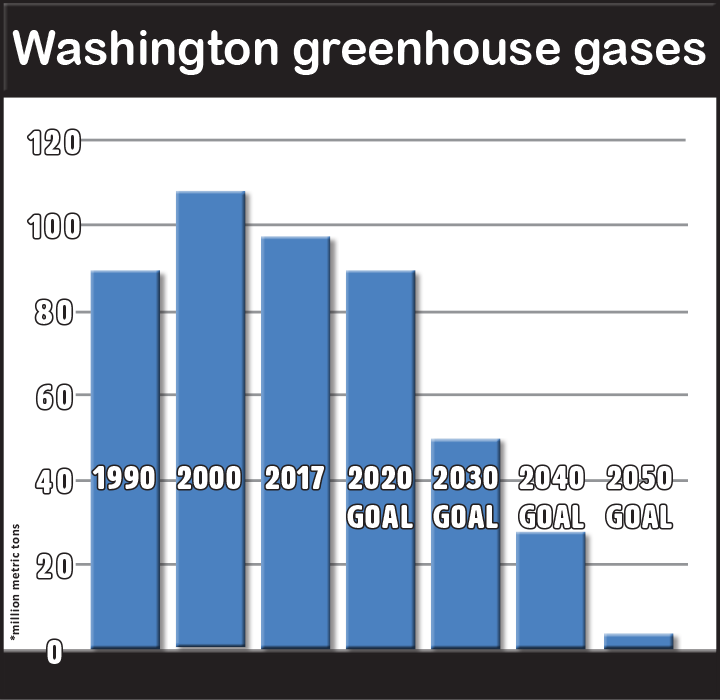

Recognizing these threats to Washington, the Legislature set aggressive new greenhouse gas targets. Washington isn’t alone in raising the bar — hundreds of other local, state, and national governments have set similar standards, based on the latest science about what emissions reductions are needed to forestall the worst effects of climate change.

Consistently and comprehensively analyzing major projects won’t by itself decide whether those projects are a good or bad idea. But crafting uniform standards will create a level playing field so that people and companies considering a new plant or a major expansion know what’s expected of them, and so the agencies and governments charged with reviewing those plans have clear guidelines to complete their evaluations.

Another benefit of creating common standards for these assessments will be building trust and transparency into the process. Major industrial and fossil fuel projects are often controversial, with people and communities lining up both for and against them. If everyone understands the yardstick by which emissions are measured, it will build confidence in the decisions being made.

The announcement of the new rulemaking only begins this process. Ecology has not come up with the standards and measurements yet, and we won’t until we talk with a wide variety of people and organizations that can give us input on the best ways to accomplish our task. And, once we develop a proposed rule, we will take that to the public and get feedback on whether the proposal achieves our goal.