Gathering PFAS samples on the Quinault River.

A new Ecology study offers more evidence that these chemicals are getting out into the environment and building up in the food chain, increasing the potential for exposure for people and animals. However, the study also offers hope that a voluntary phase-out for some of these chemicals may mean that we’re turning a corner on these exposures.

“Our new study raises concerns, definitely, but it also shows that the steps we’ve taken to address these chemicals are beginning to pay off,” said Callie Mathieu, a scientist with Ecology’s Environmental Assessment program, who led the new study.

PFAS in Washington

First, let’s do a quick recap of why we care about perfluorinated chemicals:PFAS in Washington

Earlier this year, two of these chemicals, PFOS and PFOA, were discovered in drinking water in Airway Heights, leading the town near Spokane to advise residents to drink bottled water for several weeks while the city switched over to a different water supply. Private wells on Whidbey Island were also found to contain PFOS and PFOA. In past years, the chemicals have been found in wells serving DuPont and Issaquah as well.

In all of these cases, the contamination is believed to have come from firefighting foam used to combat oil fires. Firefighting foam is far from the only use of perfluorinated chemicals, though. PFASs are found in products ranging from outdoor jackets to muffin wrappers — pretty much any product where you need a combination of oil and water resistance.

Health concernsPFOS and PFOA are the best-studied perfluorinated chemicals, and the members of the family that carry the greatest health concerns. The compounds have been shown to affect liver function, alter reproductive hormones and increase infant mortality. In Parkersburg, W.V., where the chemicals were manufactured for years, they have been linked to diseases ranging from high cholesterol to kidney cancer.

In 2002, all of the major manufacturers of PFOS in the United States agreed to stop using the chemical. In 2003, the U.S. manufacturers agreed to phase out the use of PFOA and other long-chain chemicals by 2015. Other PFAS chemicals are believed to pose less of a threat and are still widely used, although their safety is still being studied.

Despite these concerns, there are no regulatory standards for PFAS. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has set an advisory level for drinking water for PFOS and PFOA of 70 parts per trillion. The U.S. Department of Defense has been testing sites near military bases for these chemicals, which is what led to the discoveries at Airway Heights, Whidbey Island and DuPont.

Looking for PFAS high and low

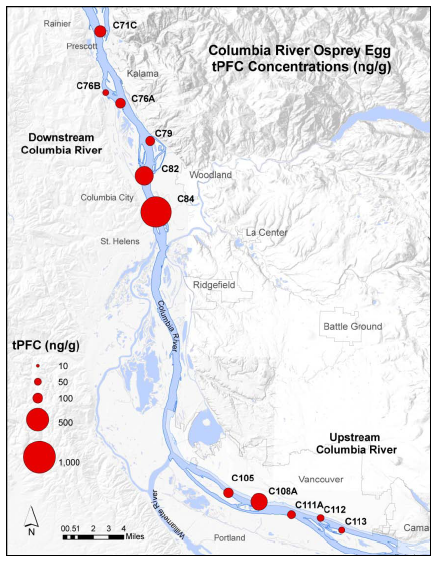

PFAS levels in Osprey eggs found in a 2008 Ecology study

We also looked at fish tissue to see whether PFAS chemicals were getting into the food chain, and at osprey eggs to see whether they were building up from prey to predators — a process called bioaccumulation.

What we found wasn’t surprising — but it wasn’t welcome news, either:

- Every lake and river we tested showed traces of PFAS. Concentrations were highest in urban waters.

- Every sample from a wastewater treatment plant contained PFAS.

- Sixty seven percent of the fish we sampled had traces of PFOS in their livers.

- All of the osprey eggs we tested contained PFAS, and at higher levels than we found in the fish, indicating the chemicals were bioaccumulating.

Once more unto the breach

Our 2008 study gave us a strong baseline of data on these chemicals, although by itself it did not provide enough information to set a fish advisory level or drinking water standard.

With PFOS and PFOA being phased out by 2015, however, we clearly needed to go back and look to see whether things were getting better or worse.

Mathieu, who co-authored the 2008 study, headed back into the field in 2016 to see what was happening. Again, she sampled lakes and rivers, treatment plant effluent, fish tissue and osprey eggs. The new study found no significant changes in the levels of PFAS in fish tissue or osprey eggs.

“Despite 15 years of phasing these chemicals out, PFOS continues to be a ubiquitous contaminant,” Mathieu said.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that there was a marked reduction in the PFAS found in the surface waters of lakes and rivers, and in treatment plant effluent. Predictably, other PFAS compounds were found to be replacing the phased-out PFOS and PFOA in effluent.

“We found urban lakes had more PFOS in the surface water and higher concentrations in fish tissue” Mathieu said. “We’re hoping to come back out in 2018 and do more sampling to figure out the sources of PFOS and provide more data to Department of Health so they can assess the data for a potential fish consumption advisory, warning people against eating fish from waters high in PFOS.”

Developing a chemical action plan for PFAS

Some PFAS chemicals are known to pose risks to human health and the environment. The safety of other members of this large family of chemicals is still being evaluated.Developing a chemical action plan for PFAS

In 2015, Ecology and the Washington State Department of Health began developing a PFAS chemical action plan to collect all the available information on the safety, potential risks, uses and alternatives to PFAS chemicals.

Working with an advisory committee composed of industry and environmental stakeholders, Ecology and Health are creating a chemical action plan that will identify how PFAS chemicals are getting into the environment and recommend the best ways to reduce or eliminate these sources.

The advisory committee met in August of this year to hear presentations on the latest findings from Ecology and Health, and to discuss potential recommendations. The committee will hold its next meeting Nov. 1 in Bellevue.

Learn more about PFAS: