Hanford tank waste management

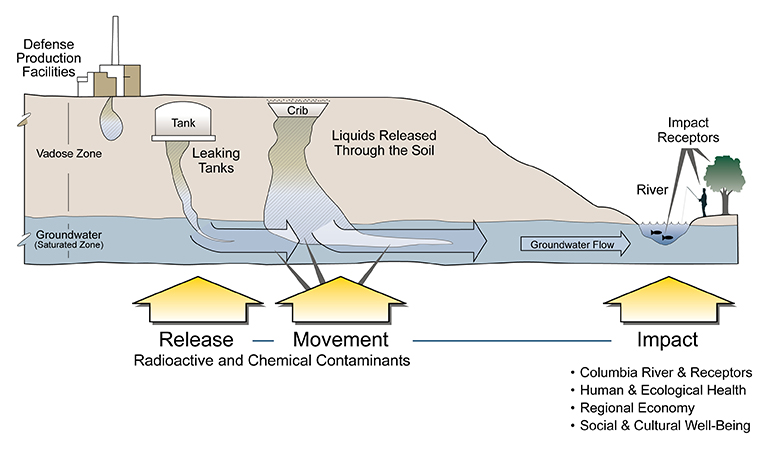

We oversee the safe storage, retrieval, and treatment of the dangerous waste in Hanford's underground tanks. There are 149 single-shell tanks and 28 double-shell tanks at Hanford. These 177 tanks hold the most dangerous radioactive and chemical wastes from decades of plutonium production activities.

Turning nuclear waste into glass

Sample of vitrified material at the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of River Protection.

For the past few decades, the most dangerous radioactive and chemical waste has been and continues to be moved from single-shell tanks to safer double-shell tanks at Hanford. The waste will remain in the double-shell tanks until it can be moved to the Waste Treatment and Immobilization Plant (WTP), which is under construction.

The Waste Treatment Plant is a complex combination of many facilities including a High-Level Vitrification Facility, Pretreatment Facility, Laboratory, Low Activity Effluent Management Facility, and Low Activity Vitrification Facility. Parts of the WTP is about to become operational including the Low Activity Vitrification Facility, the Effluent Management Facility and laboratory.

These facilities along with the Low Activity Waste Pretreatment System (which pretreat the tank waste and removes key radionuclides) will combine to treat the low activity liquid waste feed from the double shell tanks. Plans are for these to be operational in 2025. These facilities will produce Low Activity Waste containers filled with glass (a process called vitrification) waste that will be disposed of at the Integrated Disposal Facility Landfill at Hanford. It is important for any Low Activity tank waste disposed at Hanford to be vitrified as it is the robust waste form of glass that protects the aquifer beneath the landfill and the Columbia River. Other lesser waste forms have been analyzed and are not protective of the aquifer.

The other portions of the WTP are designed to vitrify the high-level waste feed from the double shell tanks. The High-Level Vitrification Facility will turn the high-level waste into glass, that will then be stored at the Hanford Site in high-grade stainless-steel canisters. This high-level glass will eventually be transferred to a deep geologic repository. While at Hanford this waste will still be highly radioactive, however the vitrified waste will no longer be able to seep into or pollute the air, water, and soil.

Without the retrieval from the tanks and treatment of the tank waste, any leakage would eventually reach the Columbia River. WTP is critical in helping to clean up Hanford and in reducing the possibility of further threats to the environment and all who live and work near the Columbia River.