Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)

Watch our video to learn how to reduce your exposure to PFAS.

PFAS can be found in a wide variety of personal, consumer, and industrial products such as:

- Nonstick cookware.

- Waterproof clothing.

- Furniture.

- AFFF (aqueous film-forming foam), a common type of firefighting foam.

- Food packaging.

While some manufacturers have moved away from PFAS, the alternatives are not always safer.

We work with the Department of Health, industry and environmental stakeholders, and community organizations to identify and take actions to phase out the use, release, and exposure to PFAS in Washington. To guide this work, we collaborate with the Department of Health to:

- Develop a chemical action plan, which recommends actions to address PFAS.

- Implement product laws that reduce the use of PFAS.

What are the health impacts of PFAS?

While the full scope of health impacts on humans is still not completely understood, experts investigating the impacts on people's health have found probable links to:

- Immune system toxicity.

- High cholesterol.

- Reproductive and developmental issues.

- Endocrine system disruption.

- Ulcerative colitis.

- Thyroid issues.

- Certain cancers.

- Pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Go to the Washington State Department of Health's PFAS page for more information.

How does PFAS get into the environment?

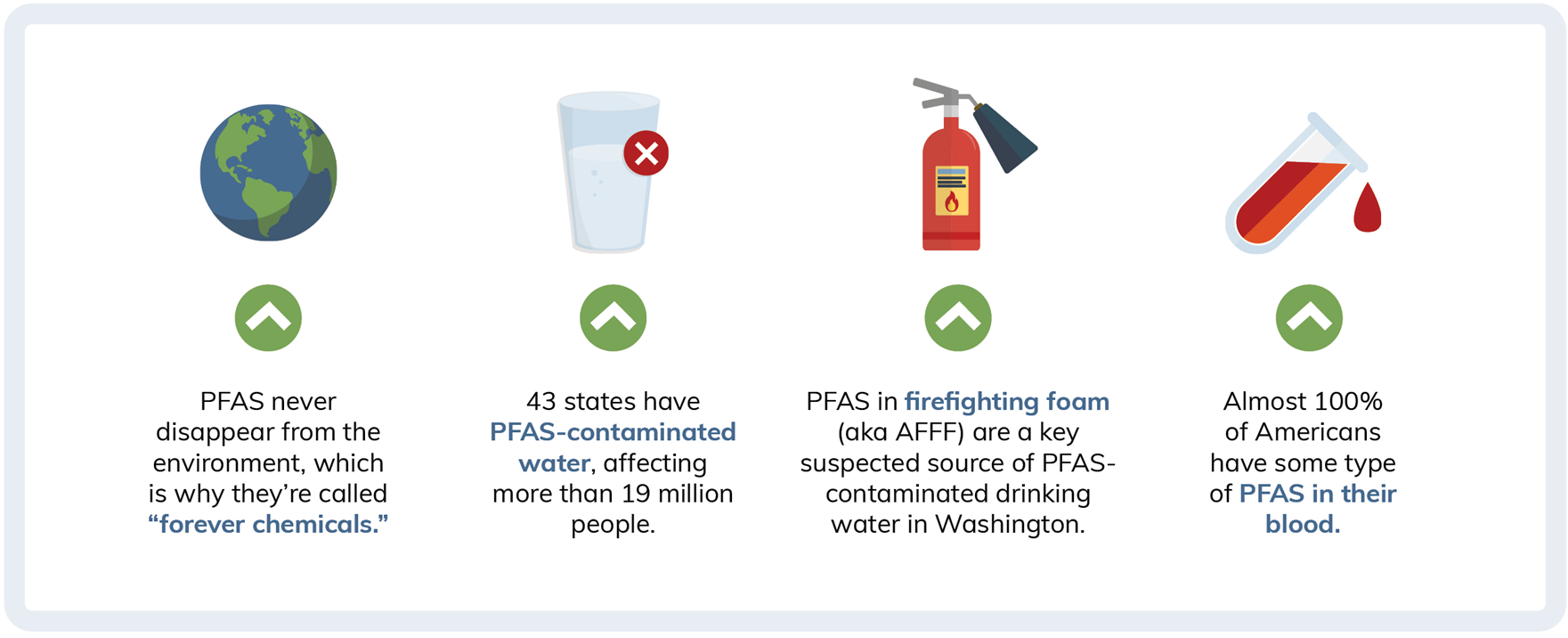

PFAS are water soluble and highly mobile. They can easily contaminate groundwater and be hard to filter out. Since these substances don’t break down naturally, our exposure to PFAS could continue for hundreds or thousands of years.

- 43 states have PFAS-contaminated drinking water, affecting more than 19 million people.

- AFFF is a key suspected source of PFAS-contaminated drinking water in Washington.

- Almost 100% of Americans have some type of PFAS in their blood.

What products may contain PFAS?

PFAS are used because they are oil- and water-resistant. These properties make them appealing to manufacturers because of their wide application and uses. Some manufacturers have moved away from PFAS but the alternatives are not always safer.

The following are examples of the wide variety of products that may contain PFAS, but this is by no means an exhaustive list.

- Stain- and water-resistant textiles:

- Outdoor and upholstered furniture.

- Mattresses.

- Carpets.

- Waterproof clothes and gear:

- Raincoats and jackets.

- Hiking boots and backpacks.

- Nonstick cookware

- Food packaging with grease and waterproof coatings, such as:

- Popcorn bags.

- Fast food wrappers.

- Takeout containers.

- Cosmetics.

- Food processing equipment (such as tubing in ice cream and soda dispensers).

- Paints and sealers that promote a smooth finish.

- Floor, automobile, and ski waxes and polishes.

- Firefighting foam (otherwise known as AFFF) used to fight fuel-based fires.

Read our guide to learn how to reduce your exposure to PFAS.

Actions Ecology has taken to reduce or eliminate PFAS

Frequently asked questions

Related links

Contact information

Chemical Action Plans Team

ChemActionPlans@ecy.wa.gov