Natural action - with some assistance - can reduce a plume of contaminated groundwater outside of the Boeing Auburn plant.

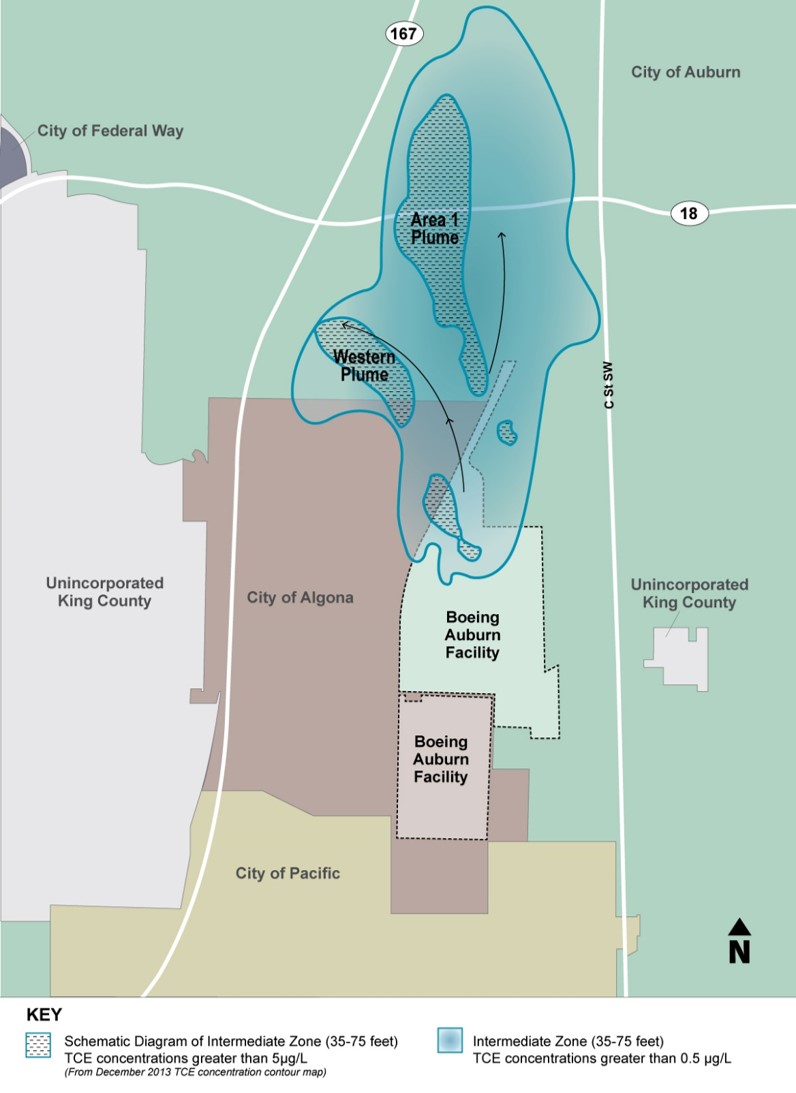

We’re overseeing the Boeing Company’s environmental cleanup at its parts fabrication facility in Auburn. Part of the contamination extends beyond Boeing’s property line as a plume of contaminated groundwater under Northeastern Algona and Northwestern Auburn. The plume reaches about a mile, mainly north and a little bit west of the plant.

TCE plume: the remedial investigation mapped and measured the where groundwater is contaminated.

The plume contains a solvent called TCE, or tri-chloro-ethylene, that is believed to have leaked through cracks in concrete floor basins from the 1960s to the 1990s. Since that time, Boeing has switched to less toxic solvents and complies with hazardous waste requirements adopted to prevent spills and leaks into the environment.

Decades of study and progress

From 2002 to 2017, Boeing conducted detailed studies — called a remedial investigation — that we oversaw. These studies mapped the affected areas. By the end of the study, Boeing had installed over 300 wells to map and measure the TCE plume.

In 2005-06, Boeing conducted a cleanup on its property of an area with very high concentrations of TCE in groundwater. This cleanup slowed or stopped the spread of TCE outside of Boeing’s property.

This truck-mounted probe was one of the tools used to gather soil and groundwater samples. TCE concentrations found were below levels known to cause health effects.

A very important finding was that the level of TCE in the off-property plume is too low to affect the health of people living in the area. Also, northwest of Boeing property, the studies found that seasonal ponds or large puddles that form in the winter contain TCE at levels too low to harm people or animals who touch the water, or animals that drink it. Fruits or vegetables grown in the area were found to be safe to eat.

The area’s drinking water is piped from wells that are not located near the plume, and is safe to drink.

The next step

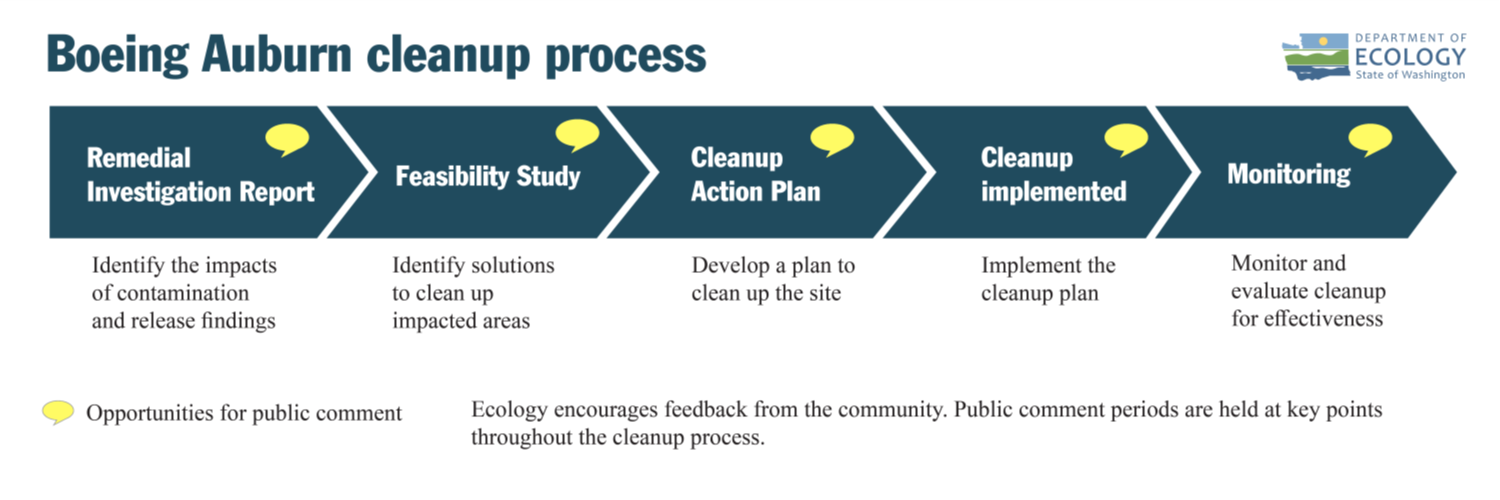

While this is good news, the plume still must be cleaned up. Having learned so many details about the plume, we directed Boeing to take the next step: study the best ways to clean it up. We’ve received that study, and a supplement to it in answer to questions we asked. We’re sharing these with the public for comment. After the comment period, we’ll decide whether to approve these studies, which will enable us to move the process to the next step: a cleanup plan.

The studies, officially called feasibility studies, show two approaches to tackle the plume. Each could work in different parts of the affected area.

Enhanced bioremediation

Served by the tankful

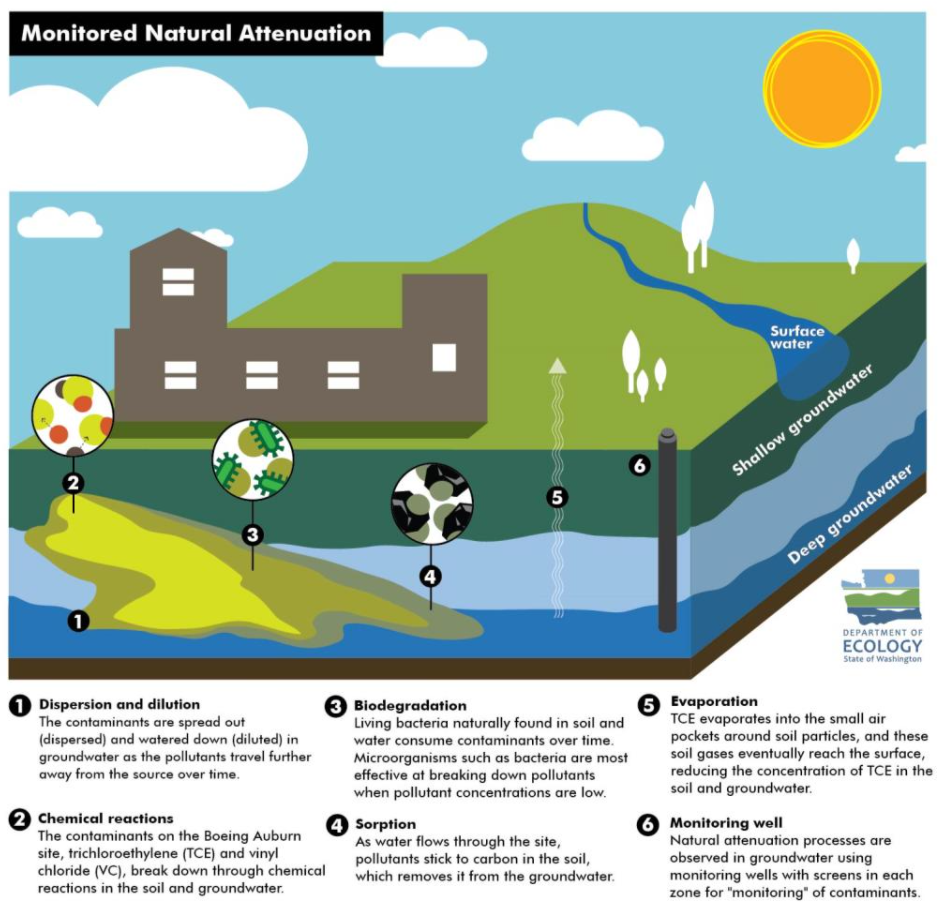

Bioremediation is a process where bacteria that naturally live in the soil “eat” the chemical contaminants. This process can be enhanced by adding non-toxic food (sugars and carbon) into the groundwater so the bacteria grow faster and eat more chemicals.

We asked Boeing to try this out. With the cooperation of a business in an Algona office park, Boeing’s contractor installed wells and poured in bacteria food. And it worked! The feasibility study reports that this method can help speed the cleanup in more central parts of the plume that have relatively higher concentrations, compared to the outer parts.

A computer model showed that using enhanced bioremediation in the Algona area should reduce the time needed to meet our water quality cleanup standards by more than half.

Monitored natural attenuation

Where TCE levels are relatively low, or in places where it’s not practical to install wells to feed bacteria, the bacteria are still there. They’ll still pick away at the TCE at their normal pace, along with other natural processes that chemically break down and dilute TCE concentrations.

Click to englarge this chart.

Collecting and analyzing samples would make sure that the concentration of chemicals in the soil and groundwater is declining.

What happens next?

We're at the second step, proposing to adopt the Feasibility Study, after we consider all public comments.

After the public comment, we’ll review and consider all comments received. The feasibility study documents may change based on your comments. We expect to propose a cleanup action plan as early as this winter. We’ll ask for your comments on that too.

All through these processes and throughout the cleanup, monitoring will continue. Boeing submits monitoring reports four times a year, and these are available on our online document library.

Bon appetite, soil bacteria!