Wood stove smoke is the primary cause of air pollution in Washington during winter.

Today, everyone is painfully aware of the air pollution caused by wildfire smoke during our lengthening summers. But you may not know as much about the other polluting smoke that happens in our state during the opposite time of the year. It comes from wood stoves, fireplaces, and other wood-burning appliances.

Residential burning to stay warm is the main activity that creates fine particle air pollution in Washington in winter, and it puts out hundreds of times more air pollution than other heat sources, such as natural gas and electricity.

As hazardous as smoking cigarettes

“Wood smoke is the result of combustion and creates particles so small they can be inhaled deeply into lungs,” says Paul Rossow, air quality specialist in the Washington Department of Ecology’s Eastern Regional Office. “Once they get there, they don’t come out, similar to cigarette smoke.”

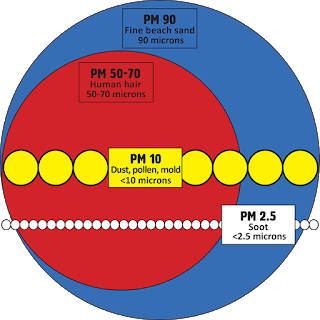

Ecology’s statewide air monitoring network monitors two types of particle pollution: particulate matter (PM)10, which are particles less than 10 micrometers in size, and PM2.5, which are fine particles less than 2.5 micrometers in size – much smaller than the diameter of a human hair.

Small particles found in smoke (PM10 and PM2.5) are smaller than a human hair.

Some of the long-term health effects of breathing in these particles from wood smoke include bronchitis, emphysema, and cancer. In fact, Ecology estimates that fine particle pollution in Washington kills more than 1,100 people every year. And that is why – when our network shows PM2.5 levels going up in one or more of our jurisdictions – we call a burn ban in the affected area.

The art (and science) of calling a burn ban

Winter burn bans are usually needed in October through March, with weather conditions determining how far into spring the burn ban season lasts.

Weather also plays a big role in pollution levels. During a temperature inversion, warm air high in the atmosphere acts like a lid, keeping cold air and pollution near the ground. This may trap unhealthy levels of smoke from wood stoves and fireplaces, triggering a burn ban to improve the air quality and protect public health.

As Ecology’s lead air quality modeler and forecaster, Beth Friedman is one of a handful of people who decide whether a burn ban should be called, and for how long. Over the past six years, she and her colleagues have called an average of four burn bans a year.

While the criteria for calling a burn ban are codified in state law, predicting when to call one is a bit of an art. It requires analyzing a range of tools and resources, including Washington’s Air Monitoring Network, AirNow’s Fire and Smoke Map, weather forecasts, and satellite and webcam imagery, as well as assessments and collaboration with experts in the field.

Friedman sums it up well: “In general, we check the air quality monitors as well as weather forecasts to understand if PM2.5 is forecasted to be greater than 35 micrograms per cubic meter within the next 48 hours.”

It’s one thing to know when air pollution has exceeded 35 ug/m3, but what does that look and feel like?

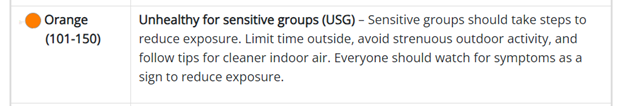

“It might be a little hazy outside with reduced visibility, and the air might smell smoky,” says Friedman. “It’s also the minimum concentration that corresponds to ‘Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups’ on the Air Quality Index. Some people might experience symptoms, including burning eyes, coughing, and throat and nose irritation.”

Burn bans occur in two stages*:

Stage 1:

- No use of uncertified wood stoves or fireplaces is allowed.

- No outdoor burning, agricultural, or forest burning is allowed.

Stage 2:

- No burning indoors or outdoors is allowed.

*Anyone using wood as their only source of heat can continue to burn, no matter the stage.

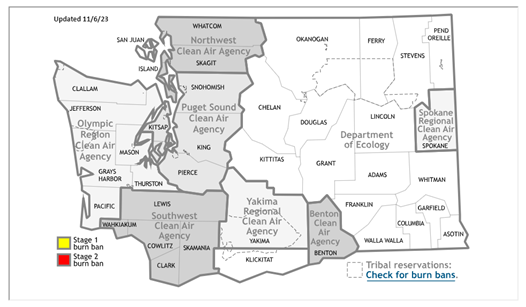

Ecology calls burn bans in the 17 counties in Washington with no local clean air agency. With the exception of San Juan County, all of these counties are located on the eastside of the state. Local clean air agencies call burn bans in counties under their jurisdiction, and the EPA calls burn bans on Tribal reservations.

Incentives to trade out and turn in

Ecology and local clean air agencies provide funding to incentivize people to upgrade older, more polluting wood stoves for newer ones at turn-in and trade-out events.

Ecology regularly holds events in areas at risk of exceeding National Ambient Air Quality Standards for PM2.5. This year, we will provide $400 to any Stevens County resident who wants to turn in and replace their inefficient wood stove. Other counties hold events where residents can trade out an old stove in return for a steep discount on a new, certified wood stove, or another even cleaner pellet, natural gas, propane, or electric stove.

“In Stevens County, wood stoves are many people’s only source of heat – you can’t just take them away,” explains Janice Batchelor, community outreach and environmental education specialist in Ecology’s Eastern Region Office. “Instead, we hold these fun events every year to help people get a more efficient, certified stove.”

Likewise, burn bans are intended to bring positive change.

“The burn ban is in place because the air quality is getting poor and affecting everyone in their community,” says Rossow. “If people comply with our burn bans, that helps the whole community.”

An old, uncertified wood stove and a new, certified wood stove.

Remember, before you burn…

- Check whether Ecology has called a burn ban in your county.

- Check whether your local clean air agency has called a burn ban.

- Check with the EPA to see if there is a burn ban on a Tribal reservation.

- Sign up for e-mails to alert you anytime Ecology calls a burn ban.

- Stay informed of air quality conditions by following Ecology on Twitter and Facebook.

- Tune in to local news and radio.

- Check with your local fire department; they will know what's happening with burn bans.