As the state agency responsible for managing water resources for Washington, we strive to ensure that there is enough water for people, farms, and fish. It’s easy to say this, but the problem is more complicated. Washington has a history of water laws that date back more than 100 years.

One tool in our water management toolbox is a process called “adjudication,” which brings all water users in a watershed into one big lawsuit. You may be thinking, “Why would Ecology intentionally use a lawsuit to fix this problem?” Well, adjudication leads to full and fair water management by finalizing legal rights to use water. The process brings all water users in a specific area into one conversation to legally and permanently determine everyone’s water rights.

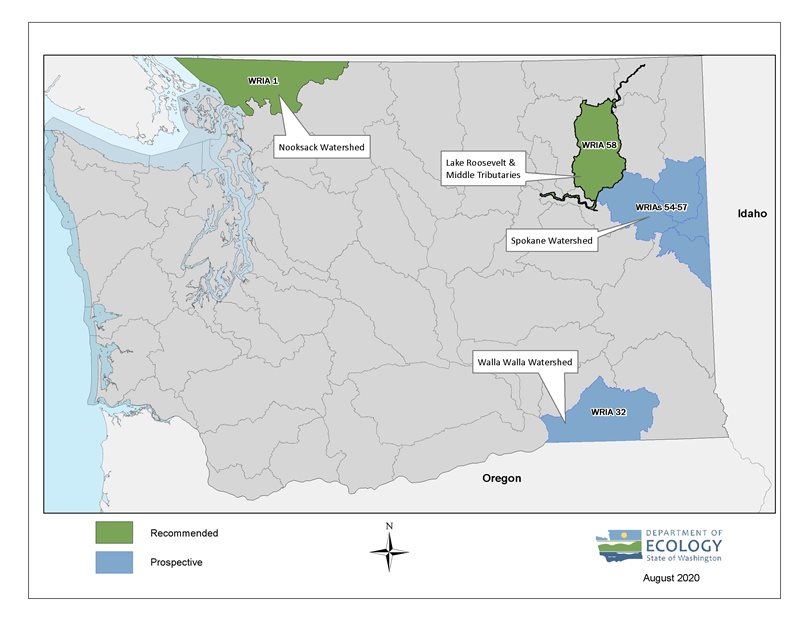

In a recent report to the state Legislature, we identified two locations that our evaluation shows would benefit from the adjudication process: the Nooksack watershed in Northwest Washington and an area around Lake Roosevelt in the eastern part of the state.

Best tool for the job

To understand adjudication, it’s important to first remember that fresh water is a limited resource. As the population around the state grows and the climate changes, we’re seeing less water available but more demand for it.

When there is not enough water for all of these uses, Washington follows the doctrine of prior appropriation. This means that the first users have rights senior to those issued later. We call this “first-in-time, first-in-right.” If a water shortage occurs, senior (older) rights are satisfied first and the junior (newer) right holders can be restricted.

Ecology, on our own, cannot apply prior appropriation throughout a watershed — only state superior courts can conduct a watershed-wide evaluation. Everyone brings their right to court, and the court decides who has a right to water, and how much. This is adjudication.

Over the years, we’ve filed many small stream adjudications in courts around the state and one large, general stream adjudication for the Yakima basin (Ecology v. Acquavella). Acquavella took several decades, but holds many lessons for modern water management. Improvements in the law and decisions made in the case will make future adjudications faster and easier. Modern technology also makes it more efficient.

Statewide assessment

Our adjudication assessment recommended two watersheds in immediate need of adjudication.

The Nooksack watershed (WRIA 1)

This watershed faces increasing pressure from water users and instream needs. Nooksack waters provide critical habitat for many species, including Chinook salmon that provide the exclusive diet for southern resident killer whales.

It’s often difficult to regulate water use in the Nooksack watershed. Water users, including tribes, all face uncertainty about their own legal rights and vulnerability to each other’s potential claims. Many water users rely on very old water rights that have not been evaluated or verified.

Lake Roosevelt and Middle Tributaries (WRIA 58)

The area in our recommendation includes the state’s largest reservoir, Lake Roosevelt, and its middle segment of tributaries in Water Resource Inventory Area (WRIA) 58. This is a rural area made up of public forest lands and some private lands. It also includes Washington’s largest Indian Reservation. The area provides valuable habitat to many fish and wildlife species.

What’s next?

The Governor’s Office will review our budget request, which will determine available resources to begin future adjudication work. We requested funding to continue the work of current adjudication staff, build technology for adjudication claim intake, and support the beginning of legal and court work. The Legislature will review the Governor’s Budget and our Legislative Report when it convenes in January.

The adjudication officially starts when we file a petition in state superior court to sue all users on a water source. This does not include water system customers or users who contract with a water purveyor. Permit-exempt well owners follow a simplified process to join —this is how we can be sure their use is protected.

The court will review everyone’s submitted documentation of their water right and water usage, and hear from water right holders. This can be done in phases and can take several years. Finally, the court issues a decree listing all users by priority date, quantity, and purpose of use. Ecology then issues adjudicated certificates which represent the final, legal water right. Everyone knows their priority date, and rights are, for the first time, no longer “tentative.”

The question of whether and where to conduct new water rights adjudications is not a simple one. Some say that in an ideal world, every watershed in Washington would be adjudicated. Others are wary of adjudication because of the cost, complexity, and disruption to the current status of water rights.

“Because of the way water law evolved in Washington, it’s imperative that adjudications are used to establish the lawful demand on a water source,” said Sid Ottem, a former Yakima Superior court commissioner who worked on Acquavella. “Having an inventory of water rights is critical to allow regulation, facilitate issuance of new rights, and encourage investment in projects to address water-short basins. Without it, we’re all just playing in the dark.”