A new report called the Washington Nitrate Prioritization Project identifies groundwater areas in the state that are most vulnerable to nitrate contamination.

Partner agencies sharing their data and helping with the project included the state Departments of Health and Agriculture, as well as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Natural Resource Conservation Service, U.S. Geological Survey, and the Washington Conservation Commission. Our data came from our Environmental Information System.

What the report highlights

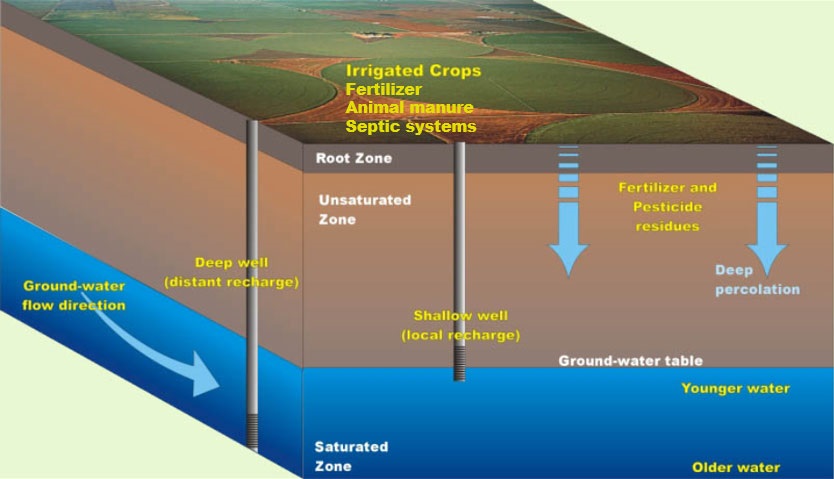

The report highlights areas in Washington that show the highest levels of nitrates in groundwater. Cross-section of groundwater shows how it is vulnerable to pollution that occurs on the land surface. Image source: USGS

This matters because groundwater is a source of drinking water for many people. Safe, clean drinking water is important.

Even though we are not the state’s drinking water experts —that’s the Department of Health — we are experts in protecting water quality, and we are working on solutions to reduce and prevent groundwater pollution.

Where nitrates come from

Nitrates can get into groundwater from many sources, including fertilizers, manure on the land, and liquid waste discharged from septic tanks. Natural bacteria in soil can convert various forms of nitrogen into nitrate. Nitrates make a good fertilizer for plants, but when there is more fertilizer than plants can use, rain or irrigation water can carry nitrates down through the soil into groundwater.

Washington is seeing a rise in nitrate contamination in groundwater. Both public water supply wells and individual residential wells have been contaminated in some areas of the state. Among others, these include the Sumas-Blaine Aquifer in Whatcom County, the Lower Yakima Valley and the Columbia Basin. Millions of dollars have been spent to deal with nitrate contamination of groundwater.

Helpful information

The Washington Nitrate Prioritization Project consolidates existing nitrate level information in groundwater areas in Washington. Our goal is to help the public — as well as local and state health and government decision-makers — be better informed about risk. Having access to this data in one location supports our efforts to protect the problem areas. Ecology's Laurie Morgan, report author.

Keeping an eye on our groundwater health is important because once aquifers are contaminated, it is difficult for them to recover.

Prevention is far cheaper than cleanup. Treatment can cost millions of dollars. Public drinking water systems spend tax dollars to install treatment systems that remove the water contamination. Private drinking water wells have fewer options. They must test and treat their own water to make sure it is safe to drink.

If you are interested in more details, we invite you to read the Department of Health Office of Drinking Water fact sheet Nitrate in Drinking Water and the Northwest Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Units fact sheet Nitrates, Blue Baby Syndrome, and Drinking Water: A Factsheet for Families. And, you may visit our website.

Let us know what you think

If you have comments or questions, you may contact Laurie Morgan, the report’s author, at 360-407- 6483 or laurie.morgan@ecy.wa.gov.