The tentacles of the slime tube worm, Myxicola sp, are quite pretty, if you overlook the copious amounts of mucus. Photo by Dave Cowles, wallawalla.edu.

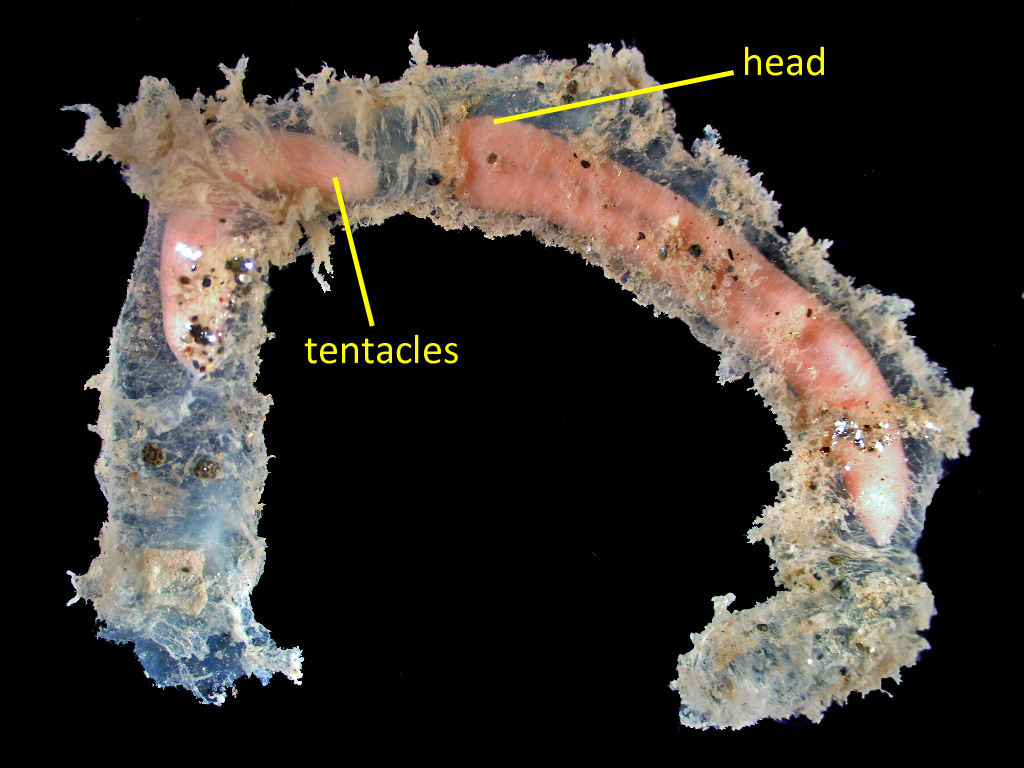

A preserved Myxicola specimen with slime tube intact.

Jelly roll

The slime tube worm (also called the jelly tube worm) belongs to a family of marine worms known as fan worms or feather duster worms, named for their beautiful feathery crowns of feeding tentacles. Most fan worms construct tubes out of mud or sand grains, cemented together with a small amount of mucus, but slime tube worms secrete so much of the stuff that they forego the extra materials completely.

The genus name Myxicola means 'living in slime,’ and the worms can sometimes be found living in slime together, their tubes fused into horrific goo balls. According to Leslie Harris, a polychaete specialist from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, a decent-sized cluster of worms can produce “enough slime to fill a 40-gallon trash can”! Even as an invertebrate enthusiast, this makes my skin crawl.

Mounds of slime worms with their tentacles extended

Slime and punishment

Many worm predators are as repulsed by slime as we are, so the slime tube worm’s unappealing house is the perfect dwelling (although perhaps lacking in curb appeal). If so much as a shadow passes overhead, the worm will quickly withdraw into its distasteful sheath. This is crucial for survival, because slime tube worms are slow to regenerate (grow back) missing parts, and if their tentacles are nipped off by a fish or crab, it could be curtains for them. A filter-feeding slime tube worm will retract into its tube at the least sign of danger. Photo by Julian Finn, Museum Victoria.

The rapid escape response that allows the worm to reduce its body length by half in a split second is the work of an unusually large nerve cord called the giant ventral axon. The powerful contraction it produces simultaneously forces wastes out of the tube, literally “scaring the poop” out of the worm, but saving its head end to feed another day.

The test of slime

The slime tube worm’s amazing nervous system has been the subject of much research, but its slime has also been in the limelight (slimelight?) recently. Studies have shown that in addition to protecting the worm from large enemies, the slime protects from the tiniest ones: bacteria. The tube’s antimicrobial properties keep harmful bugs out while allowing “good” bacteria to thrive (so well, in fact, that other animals sometimes colonize the slime tubes to feed on the cultures). Scientists are investigating whether the slime tube worm’s magical antibiotic casing might have potential uses in human medicine. A slime tube worm’s house is cleaner than it appears. Photo by Dave Cowles, wallawalla.edu.

Nightmare on Taxonomy Street

Our Puget Sound slime worm species was once thought to be the same as the European species Myxicola infundibulum, but taxonomists now suspect that it is a different species, based on the amount of slime produced and the habitat preferences (M. infundibulum lives exclusively in soft sediment, while our west coast species sets up shop in rocks crevices or on dock pilings). Just to be safe, we leave identifications like these at genus level, because there’s nothing more spine-chilling than calling a worm by the wrong name…. except for the thought of spending your entire life trapped in a slime cocoon!

Critter of the Month

It’s a ghoooooost! Nope, just a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Dany shares her discoveries by bringing us a benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.