An empty slipper snail shell (left) beside a stack of live slipper snails (right). Photo by Ecomare/Sytske Dijksen, from Wikimedia Commons.

The first days of fall are here, and nothing makes me want to pile on the cozy layers like the arrival of the Pacific Northwest’s cool, rainy season. But let’s face it…many of us have been living in our loungewear (a.k.a. “day pajamas”) all year. This month’s critter, named for the new telework uniform’s literal foundation, embodies the fashion motto of 2020: comfort is IN.

Put your feet up

Slipping through the cracks

Different views of a Crepidula fornicata shell. Photo by H. Zell, from Wikimedia Commons.

Common slipper snails are native to the east coast of the US (although east-coasters are known for being snappy dressers, and the slipper snails' laid-back attire gives them more of a west coast vibe). Unfortunately, they are now considered uninvited guests in Europe, Japan, and the Pacific Northwest, having been inadvertently delivered with shipments of the Eastern oyster in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Their lack of natural predators and ability to thrive on hard bottoms has made them a problem in Europe, where they can damage oyster fisheries. Here in Puget Sound they seem to be more innocuous, although it is possible that they compete for resources with smaller native species, Crepidula nummaria and Crepidula perforans.

When I was a kid, we loved finding empty slipper shells washed up on the North Carolina beaches — only, we called them baby’s boats. In fact, alternate common names include the boat shell, quarterdeck shell, lady’s slipper, and slipper limpet.

A pair of slippers…plus a few extra

These two young slipper snails show off their undersides. The large rounded pads at the bottom are the feet. Photo by Ecomare/Sytske Dijksen, from Wikimedia Commons.

Stacking the deck

No, this is not a giant caterpillar... it’s a slipper snail stack! Photo by Angela Johnson, Ecology

What happens if all the animals in a stack are of a single sex? Well, thanks to the slipper snail’s amazing reproductive strategy, that scenario is impossible. Every slipper snail starts out life as a male, seeking out the perfect hard surface in the low intertidal or shallow subtidal zone. After settlement, the juvenile male slowly grows until hormonal cues trigger him to change into a female, in a process called sequential hermaphroditism. The next juvenile male that comes along settles on top of the (now) female, and once he matures, he can fertilize the eggs that she holds under her foot. Afterwards, THAT male becomes a female, and a new juvenile male settles on top.

This reproductive conveyor belt results in stacks of slipper snails with the largest, oldest females on the bottom, small young males at the top, and the middle ones in the process of changing over. If the females in a stack die, the largest males change into females to replace them.

Branching out

Only one new member can join a stack at a time, ensuring that the chain length doesn’t get out of control. However, latecomer juveniles often bend the rules by scooting off to the side to form new stacks, causing the colonies to branch out in different directions. Sometimes the heavy colonies form on top of other animals like moon snails and mussels, suffocating the unlucky hosts. Now that is what I call TOO close for comfort!

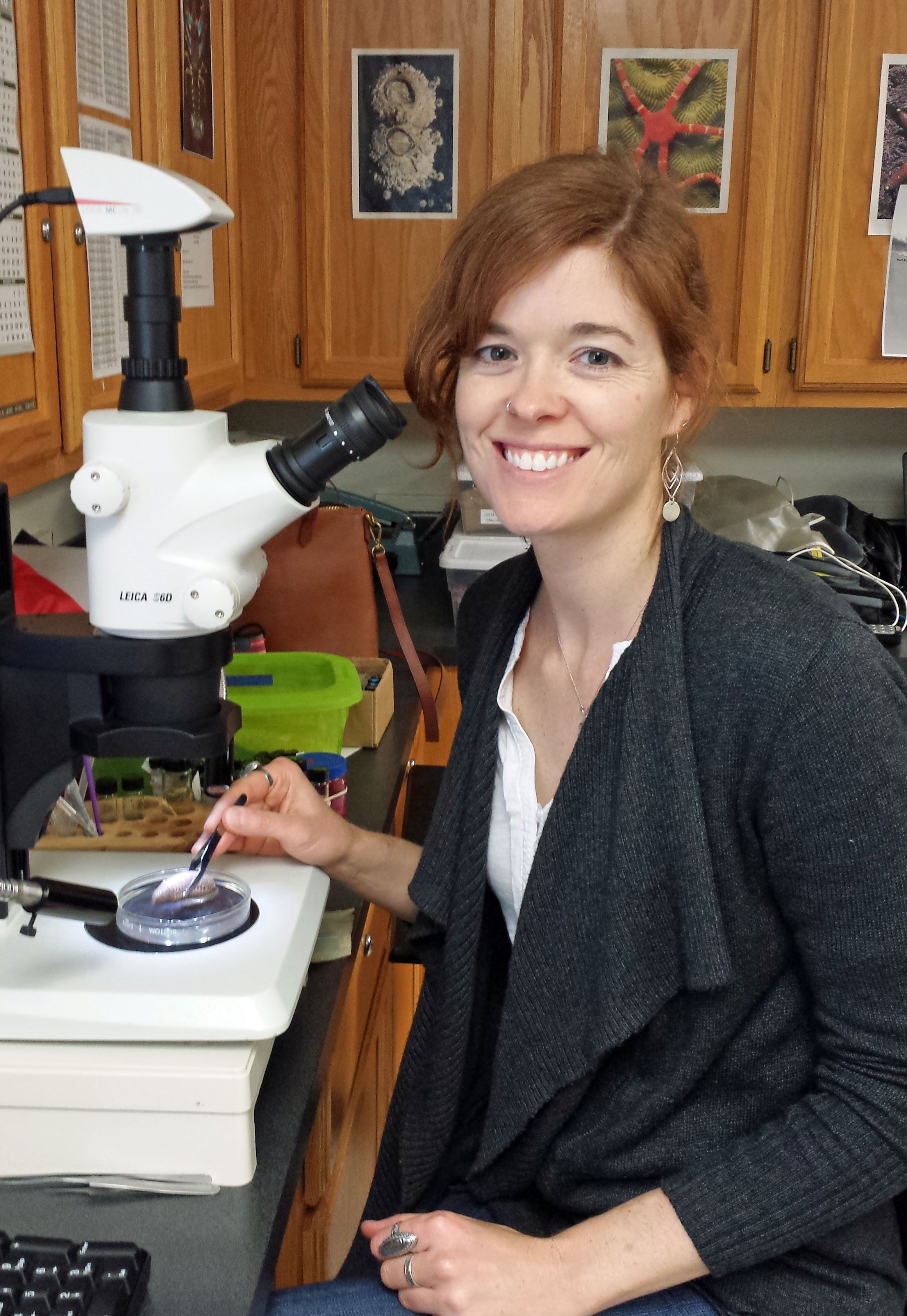

Critter of the Month

Dany is a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Dany shares her discoveries by bringing us a benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.