The lives of shell-boring worms are anything but boring, in the yawn sense. Or you could say that their lives are all about boring - into shells.

"Cockles and mussels, alive, alive-oh!"

Shell-boring worm inside burrow in oyster shell. Photo by Julieta Martinelli, UW.

Shell-boring worms are polychaetes (marine segmented worms) which make their homes in mollusc shells, such as cockles, mussels, abalone, and oysters. They don't actually bore into the flesh of the molluscs, just into the shell itself, to use as protective housing. They feed by filtering tiny organisms and bits of organic material from the water column.

These parasites are sometimes called mud blister worms, because the burrows that they create inside the shells fill with mud and detritus from their feeding.

Shell-boring worms engage in a tit-for-tat with the mollusc owner of the shell. The intrusion of the shell-boring worm irritates the oyster. (Wouldn't you be irritated if someone dug through the walls of your house?) That prompts the oyster to lay down a protective coating called nacre, isolating the precious oyster flesh, but still allowing the worm to keep boring and making its home inside the shell even bigger. This process can go on and on for months and years, resulting in large blisters filled with mud and worms that make the oyster shell look very unappealing!

Polydora websteri

In Puget Sound, researchers at the University of Washington have an interest in understanding the history and consequences of shell-boring worms, in particular a species called Polydora websteri. Polydora websteri is most likely not native to the Pacific Northwest and is found all over the world. The global distribution of this parasite is likely due to accidental spread by humans from moving bivalves around the globe for decades or longer. Left: Polydora websteri with feeding palps extended. Photo by Julieta Martinelli, UW. Right: P. websteri classification overlaid on an Olympia oyster, Ostrea lurida. Photo by G. Gillespie.

The UW researchers have recently found P. websteri (along with other related shell-boring worms) in Pacific oysters in Oakland Bay and Totten Inlet. They want to find out how widespread P. websteri and its friends are in Puget Sound, how long the worms have been here, and how humans can help minimize negative consequences to the area's prized shellfish industry.

As part of Ecology's annual sediment monitoring in Puget Sound, the sediment team has found P. websteri occasionally since the 1990s, in Oak Harbor, Discovery Bay, and Liberty Bay. We sample soft sediments, but sometimes we encounter shells or shell fragments where the worms might have been living.

What about MY oysters?

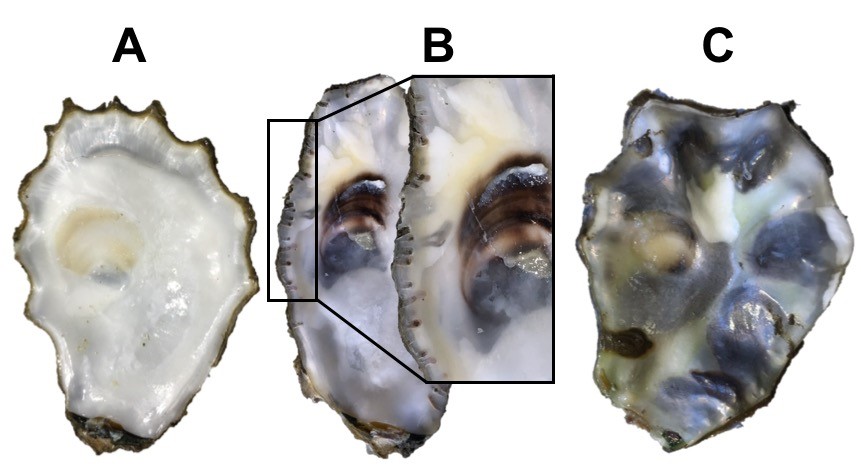

PNW oysters are well-known for their white pearly shells. While the shell-boring worm parasite is not harmful to humans in any way, you may still want to know what it looks like! Most of the marks in oyster shells can be seen with the naked eye, and they can be either ‘burrows’ or ‘blisters’. Burrows are small canals, usually on the shell edge, while blisters are larger, darker bumps. Even if you find some of these marks in shells you can still enjoy your tasty oyster. The yummy flesh is not touched or altered by the worm, so your delicious meal is not at risk. Pacific oyster shells in various stages of worm infestation.

At this point you may be wondering why the presence of this worm is so important! While not harmful to humans, the presence of blisters in shells may be unappealing for some consumers. This impacts the marketability of the product. In the United States, Pacific oysters contribute more than $219 million annually to the nation’s economy. Washington State is the largest producer of aquaculture bivalves in the country.

Olympia oysters

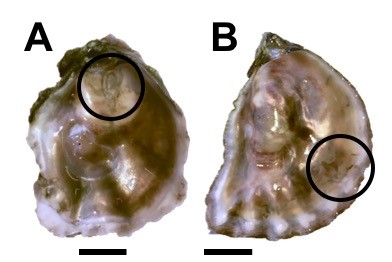

Olympia oyster shells showing traces of shell-boring polychaetes. Photo by Julieta Martinelli.

While Pacific oysters are the main oyster in terms of aquaculture production, our native oyster, the Olympia oyster, is also ecologically, culturally, and environmentally very valuable. Many organizations (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Puget Sound Restoration Fund, and NOAA) working on the restoration of this species have made substantial strides toward re-establishing Olympia oyster populations. The success of their efforts might be threatened by these shell-boring pests. Researchers at UW are also trying to understand if the worms that affect Olympia oysters are native or invasive, and what this means for restoration efforts.

Guest authors Valerie Partridge (Ecology) and Julieta Martinelli (University of Washington)

Valerie, a member of the sediment monitoring team for 20 years, is a statistician and estuarine ecologist. She spends most of her time analyzing the data from our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Critter of the Month

The Critter of the Month posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.