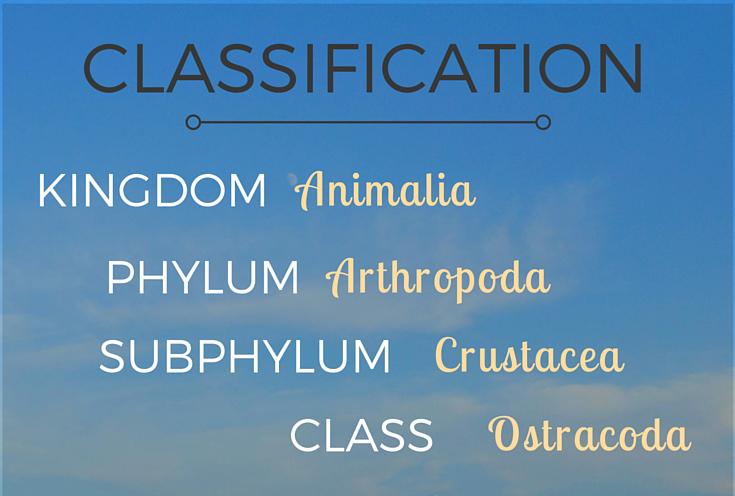

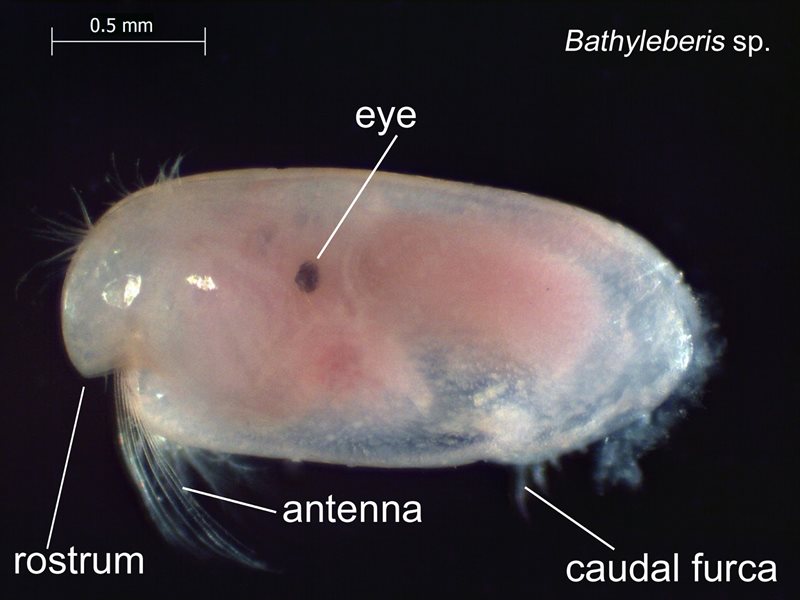

This month we bring you an entire group of nifty little critters collectively known as the ostracods, or seed shrimp.

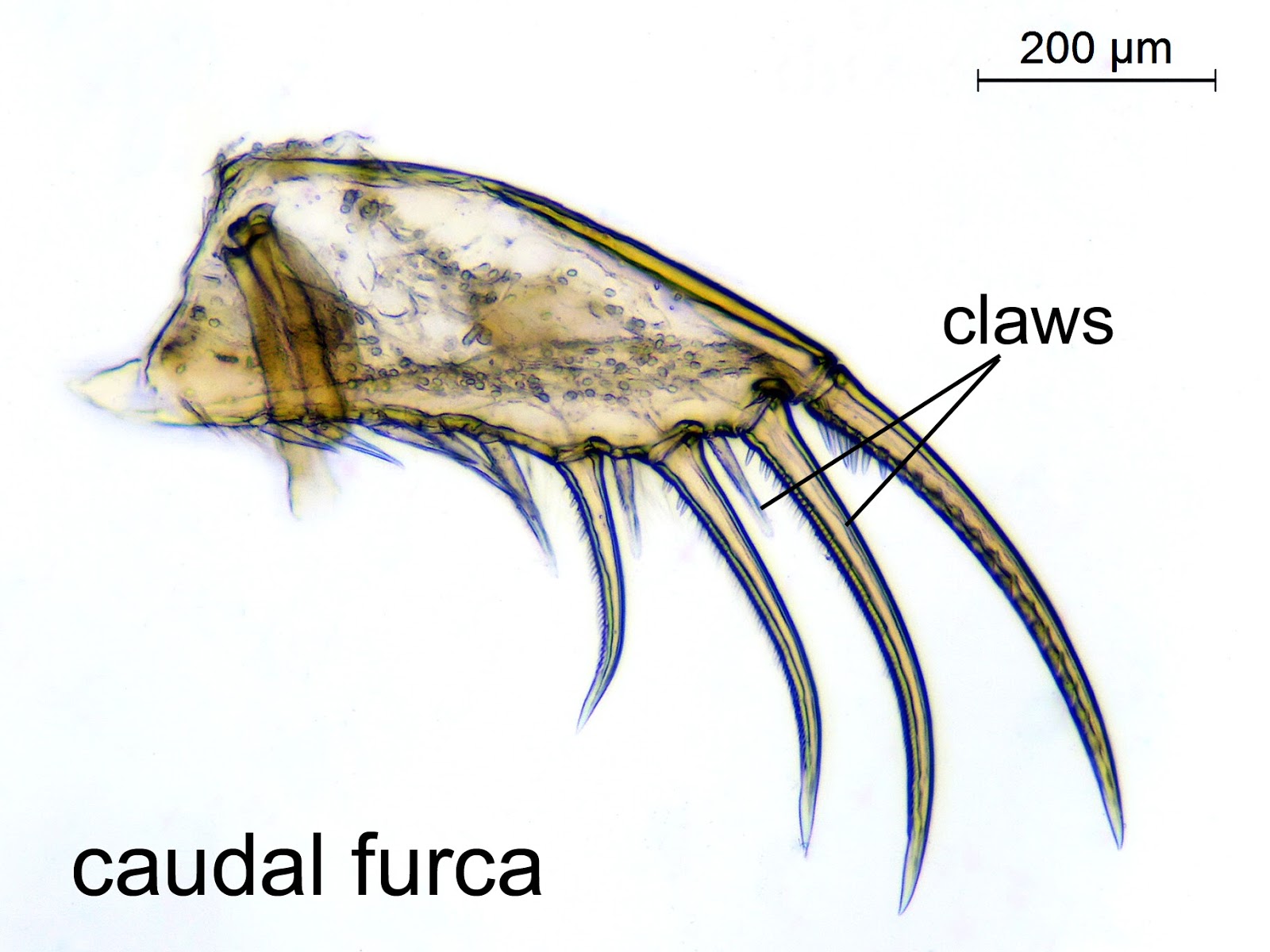

Ostracods are crustaceans, but you would never know it – their crustacean appendages (such as the foot-like caudal furca, pictured to the right) are hidden inside a clam-like “shell,” or carapace, made up of two hinged valves. Close-up of an ostracod's caudal furca, an appendage used for locomotion and/or feeding. The length and number of claws helps us identify the species.

Here, there and everywhere

With over 8,000 living species worldwide (more than any other crustacean group), we should be bumping into ostracods everywhere—at the beach, in fishing nets, or on the menu at local seafood restaurants.

In reality, most people will never see an ostracod, because the majority of species (including those that live in Puget Sound) are only about the size of a sesame seed. They spend most of their time buried in the mud or sand, filtering food out of the water with their feathery antennae.

Driven to drink (water)

Ostracods need water to live, but that doesn’t restrict them to oceanic habitats or even aquatic ones. In addition to extreme environments like the deep sea, caves and polar regions, ostracods can survive where water is scarce because they have unique strategies for dealing with drought.

One type of ostracod can trap water in its shell and move over land until its reservoir runs dry. Other types can be carried from place to place on the feet of birds or even on the backs of toads.

When all else fails, their amazing eggs remain viable for years even after drying out, hatching as soon as they are exposed to water. In fact, if you have a fish tank, you might have acquired some of these tiny stowaways in your aquarium gravel!

He said, she said

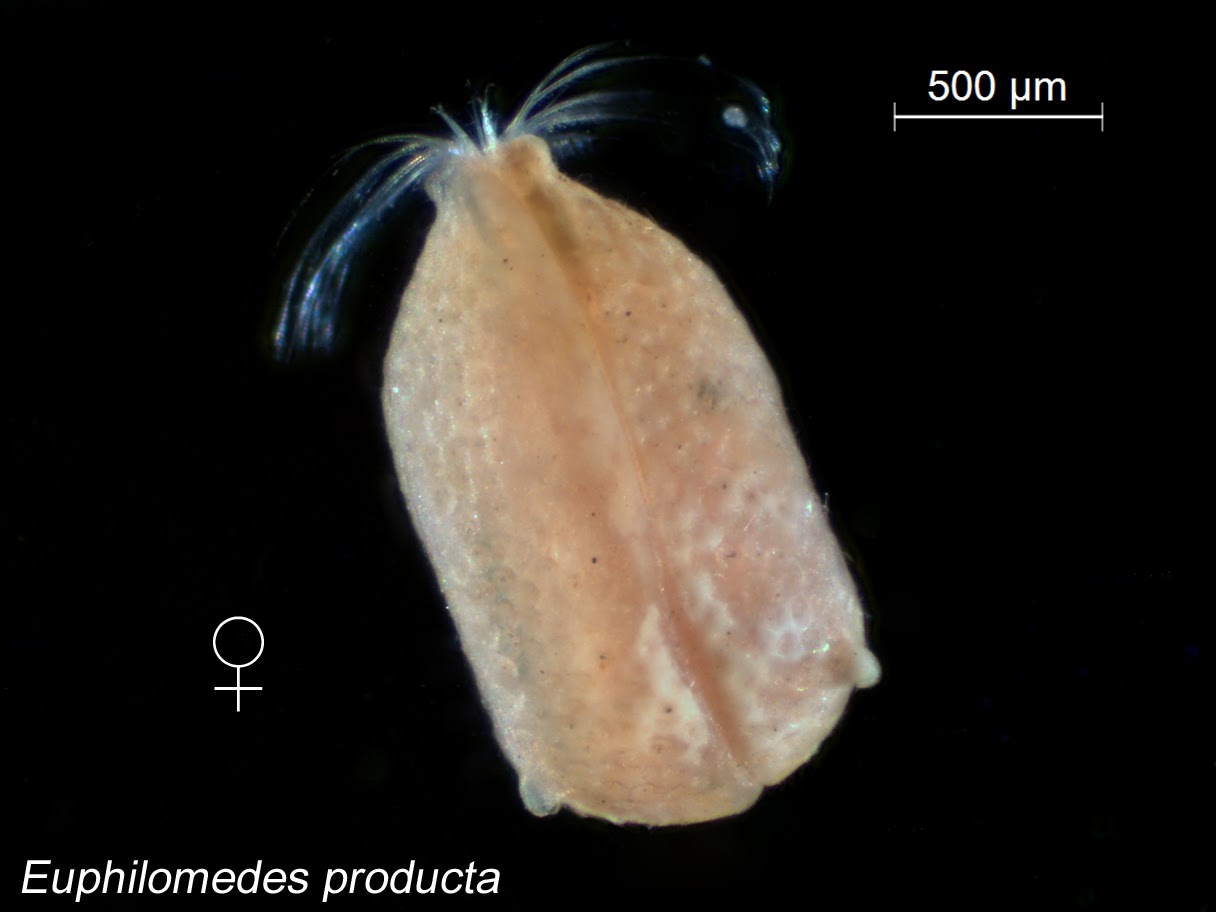

The ostracod female on the left, looks quite different from the males on the right.

The ornamentation of the carapace can vary from species to species – some are smooth, while others have ridges, bumps or pits.

They also display sexual dimorphism in carapace size and shape, meaning that males and females of the same species might look drastically different from one another (see the photo to the right.) A few species don’t need the opposite sex at all – they can reproduce asexually by cloning themselves.

Seeds of change

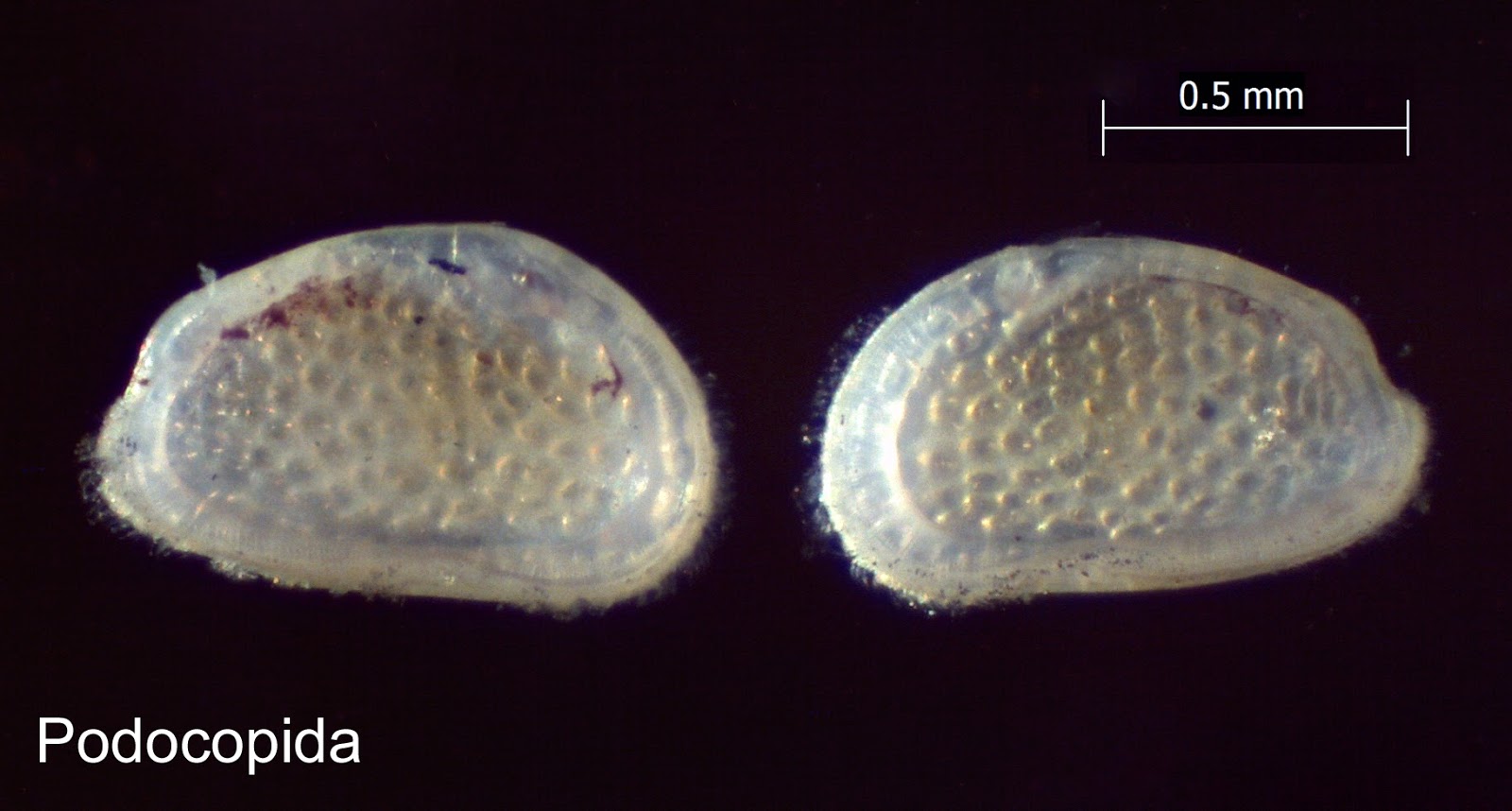

Just like oysters, ostracods use minerals in the surrounding water to build their shells.

Ostracod shells contain low-magnesium calcite, a substance that fossilizes so well that they have the most complete fossil record of any animal, dating back 425 million years to the Cambrian period! Scientists can use these ostracod fossils to help figure out how our planet and its climate have changed through time.

Critter of the Month

Our benthic taxonomists, Dany and Angela, share their discoveries by bringing us a Benthic Critter of the Month. Dany and Angela are scientists who work for the Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants.

In each issue we will highlight one of the Sound’s many fascinating invertebrates. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role this critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr. Look for the Critter of the Month on our blog.