Lewis’ Moon Snail with its dark brown, hard operculum. Courtesy of Linda Schroeder—PNW Shell Club.

With its easily recognizable shell (the largest found on Puget Sound beaches), we are certainly over the moon for this month’s critter: the moon snail.

Full moon

When we talk about moon snails, we are referring to a group of species within the family Naticidae.

Here in the Pacific Northwest, we see a few different species. Lewis’ moon snail is the largest of the moon snails — it can grow to 14 cm! Although it is the most common species overall, we don't often encounter Lewis' moon snail during our subtidal Puget Sound sediment monitoring because it lives in intertidal habitat.

The pale moon snail and Arctic moon snail are more commonly encountered during our sediment monitoring, and can be found in soft muddy bottoms from 0 to 500 meters (although Puget Sound depths reach only about 300 meters).

Cute as a (belly) button

While the different moon snail species look and act similarly, there is one thing that sets them apart — their “belly buttons.” This special belly button is called an umbilicus, and it is formed because of the way a snail shell grows around a central axis (columella). This growth results in a hollow tube running through the center of the shell, forming the belly-button-like hole. In some species of moon snails, the hole is filled in with calcium as the animal grows, but in others, the umbilicus is never filled in — so this trait of having an “outy” or an “inny” can set them apart.

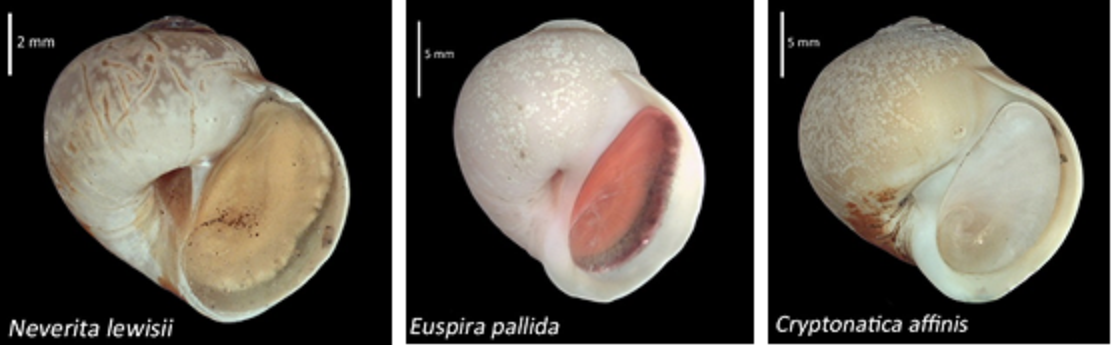

The three moon snails we commonly encounter in Puget Sound can be easily identified by the umbilicus.

LEFT: Lewis’ Moon Snail, Nevertina lewisii, has a deep umbilicus.

MIDDLE: The Pale Moon Snail, Euspira pallida, has a partially covered umbilicus.

RIGHT: The Arctic Moon Snail, Cryptonatica affinis, has a completely covered umbilicus.

Get your foot in the door

Lewis’ Moon Snail with its inflated fleshy foot engulfing almost the entire outer shell. Courtesy of Kevin Lee, www.diverkevin.com

Believe it or not, moon snails can live to be up to 15 years old, and they don’t survive that long on luck alone. When a moon snail senses danger or is disturbed, it withdraws its inflated foot inside its shell, sealing the opening (aperture) of the shell with a hardened door (called an operculum) so that the soft fleshy foot is fully protected. Meaning “little lid” in Latin, the operculum is present in almost all snails. Animals that would love to munch on a moon snail include octopuses, rock crabs, sea gulls, and even other moon snails.

The dark side of the moon (snail)

While the unassuming moon snail appears super cute and squishy, it is actually a voracious predator, using stealthy tactics to consume its favorite food, clams. It all begins when the moon snail smells its prey and uses its huge slimy foot to engulf its victim. Once the moon snail gets the unsuspecting clam in its grip, the radula goes to work. Almost all snails have a toothed structure called a radula which they use to consume smaller animal pieces or to scrape algae off rocks.

An upside-down Lewis’ Moon Snail with a clam in its huge foot. Courtesy of Linda Schroeder — PNW Shell Club

However, in the moon snail’s case, the sharp-toothed radula is used as a drill to bore holes into the hard shells of clams.This is an extremely slow process, with the average moon snail takedown lasting 4 days as it drills ½ mm per day. In order to speed things up a bit, the moon snail produces hydrochloric acid and other enzymes to help dissolve the shell and liquefy the clam’s insides.

This hole drilled on the top of a clam’s shell is the sign of a moon snail attack. Courtesy of Central Coast Biodiversity

Once a perfectly rounded hole is made in the shell, the moon snail inserts its tubular, straw-like mouth and slurps up the “clam smoothie” inside. It can take another day or so for the moon snail to ingest the clam innards. Talk about delayed gratification!

Hot under the collar

An egg-filled sand collar left on the beach by a moon snail. Courtesy of Linda Schroeder — PNW Shell Club

A few weeks go by, and the eggs hatch, breaking through the disintegrating collar and swimming away to repeat the process all over again.

Critter of the Month

Our benthic taxonomists, Dany and Angela, are scientists who identify and count the benthic (sediment-dwelling) organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see in order to understand the health of Puget Sound and detect changes over time.

Dany and Angela share their discoveries by bringing us a Benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.