Bringing home the bacon

It’s the pits

A tunicate amphipod

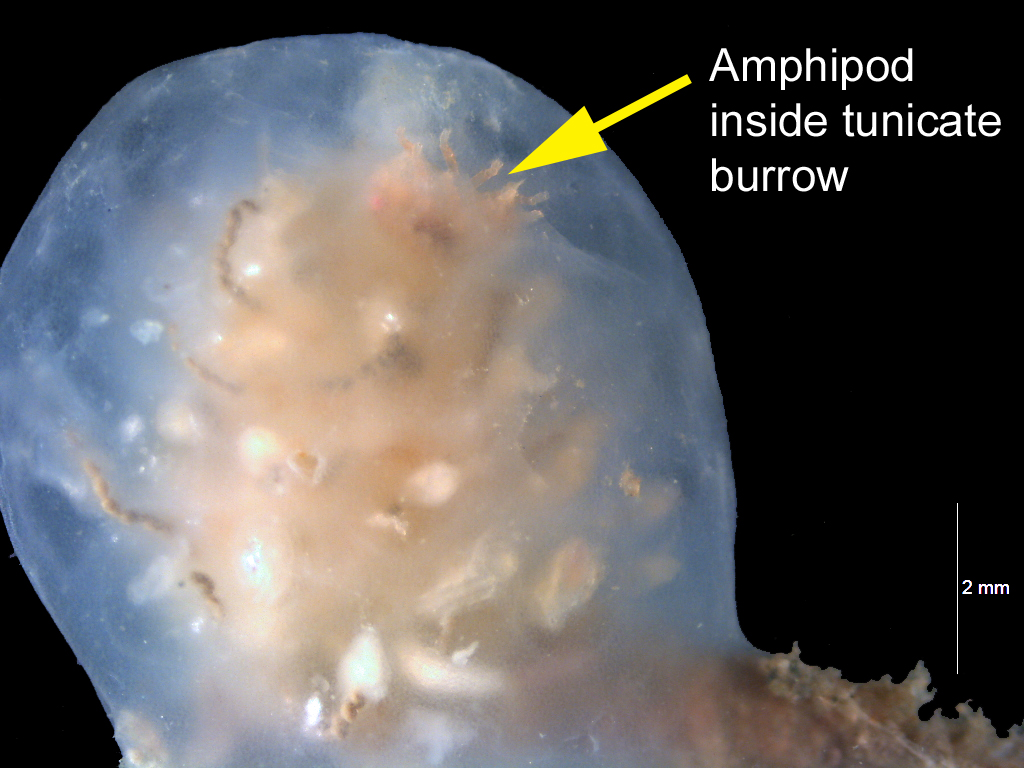

Home body

Lying on its back with its feet and antennae pointing skyward, this amphipod is the ultimate professional lounger. Don’t let the relaxed posture fool you, however — there’s actually a lot of hard work going on! The amphipod’s swimming legs, called pleopods, are constantly beating, circulating water to create feeding currents. As the water passes the antennae, tiny hairs called setae catch particles of food (like diatoms and other algae), which are collected by the claws and passed to the mouthparts. This tunicate amphipod was disturbed and emerged from its host pit. You can see how particles stick to the antennae

Close quarters

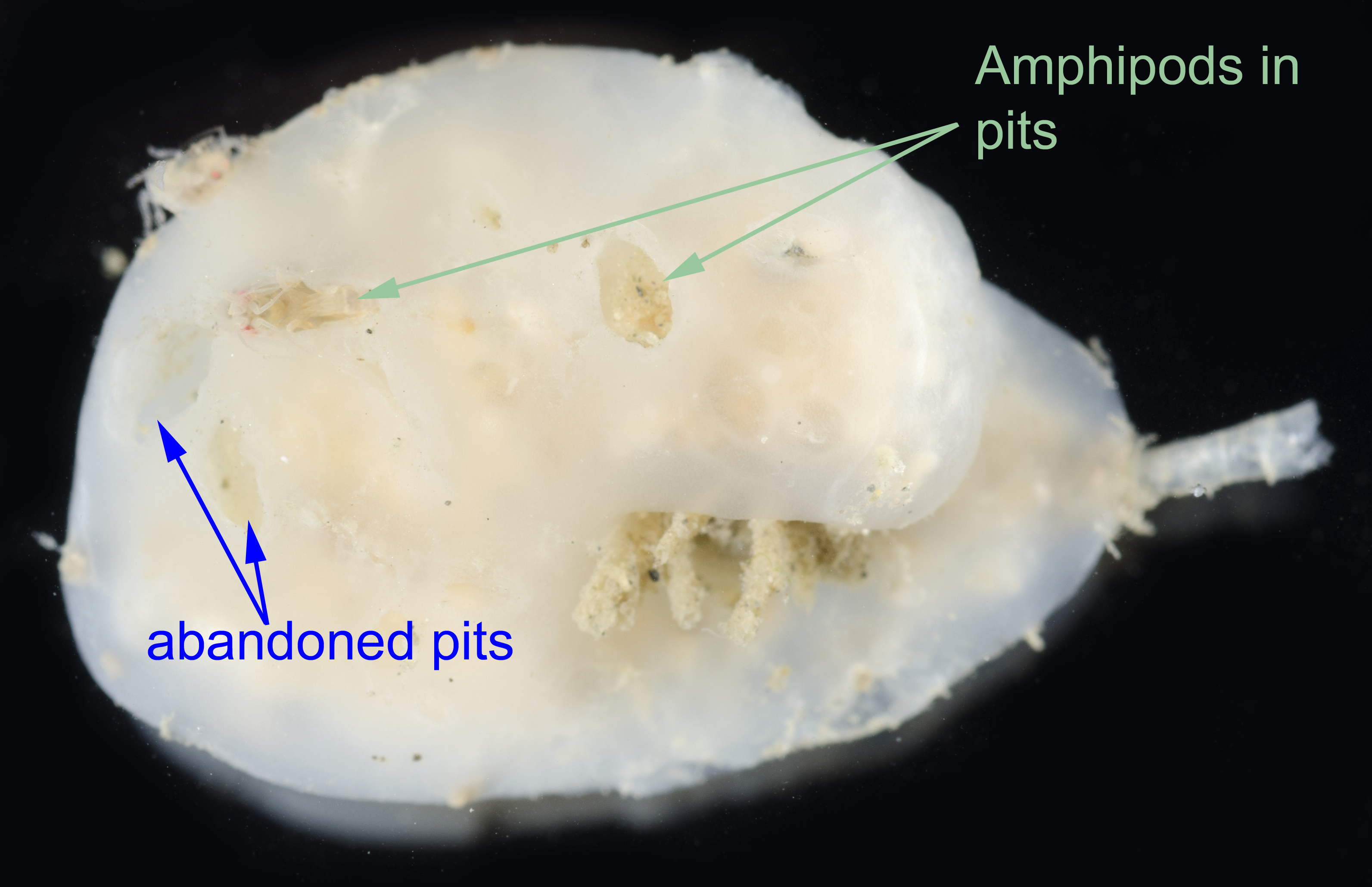

Although the tunicate amphipod is a hermit, it isn’t great at practicing social distancing. One host tunicate colony may have multiple burrows in it, kind of like rooms in a boarding house. This happens because juveniles hang out in their mother’s burrow after hatching out until they are large enough to survive on their own. When they emerge, some of them find abandoned burrows nearby to move into.

Communal living may seem like a good idea, but it has potential drawbacks — limited dispersal could mean that gene flow between groups of Polycheria stays low, resulting in fewer adaptations that could help the survival of the species over time. A tunicate with several amphipod pits in it, both occupied and unoccupied

Critter of the Month

Dany is a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Dany shares her discoveries by bringing us a benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.