Spring is finally here, and life in Pacific Northwest forests, farms, and backyards is beginning to replenish itself after the long winter. While spring might bring to mind chirping chicks and fuzzy bunnies, marine mud-dwellers are busy proliferating too, in ways vertebrates only dream of. In this Critter edition, let’s dive into the “birds and the bees” of benthic worms, and the resulting faces that only a mother (or an invertebrate taxonomist) could love. Adorable, or revolting? You be the judge. I discovered these spionid worm babies in a mud sample under my microscope, in a tube no wider than a few grains of sand.

Baby boomer

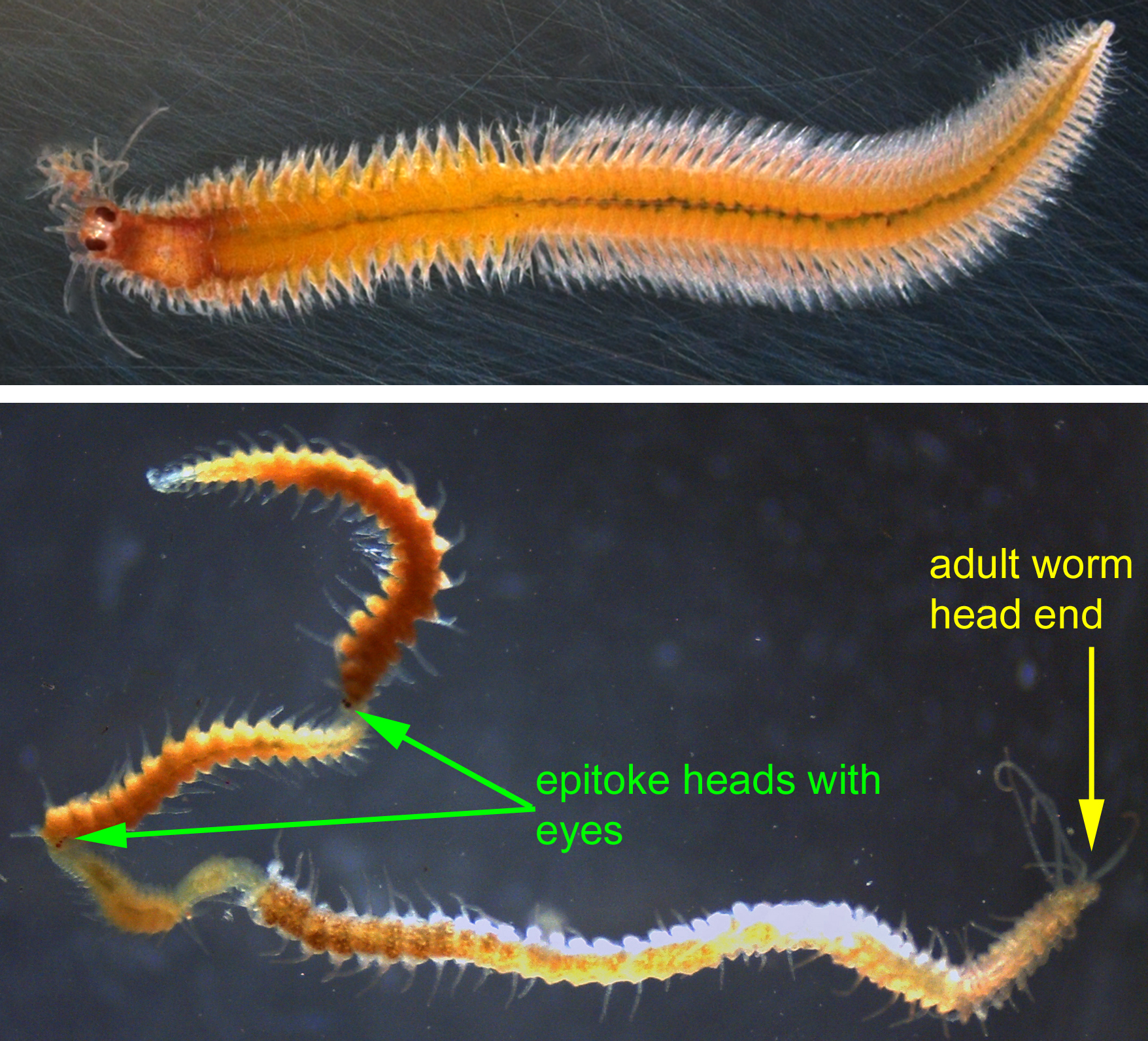

Imagine this: you are a marine segmented worm, or polychaete, in the family Nereididae, crawling across the Puget Sound mud. Environmental cues tell you that spring spawning season has arrived, and you respond by morphing into your reproductive alter ego, called an epitoke. You stop eating, and your body fills up with eggs or sperm. Your eyes grow large, and your feet turn into swimming paddles. These new features allow you to fight your way toward the surface, where you meet many other epitokes swarming together. Hooray! You have reached your objective. Top: Nereid epitoke with body full of yellow eggs; photo by Martin Gühmann. Bottom: Syllid with epitoke buds; photo by Megan McCuller. Both from Wikimedia Commons.

Your triumph is short-lived, however — this will be a one-way trip. Soon all the epitokes’ bodies (including yours) will burst, releasing gametes into the water to begin a new generation.

Your rear end did WHAT?

Not all polychaetes sacrifice themselves in this way. Some worms in the family Syllidae “grow” epitoke buds, complete with eyes, on their rear ends. These epitokes break off and swim away, leaving the adults to spawn another day.

Fur baby

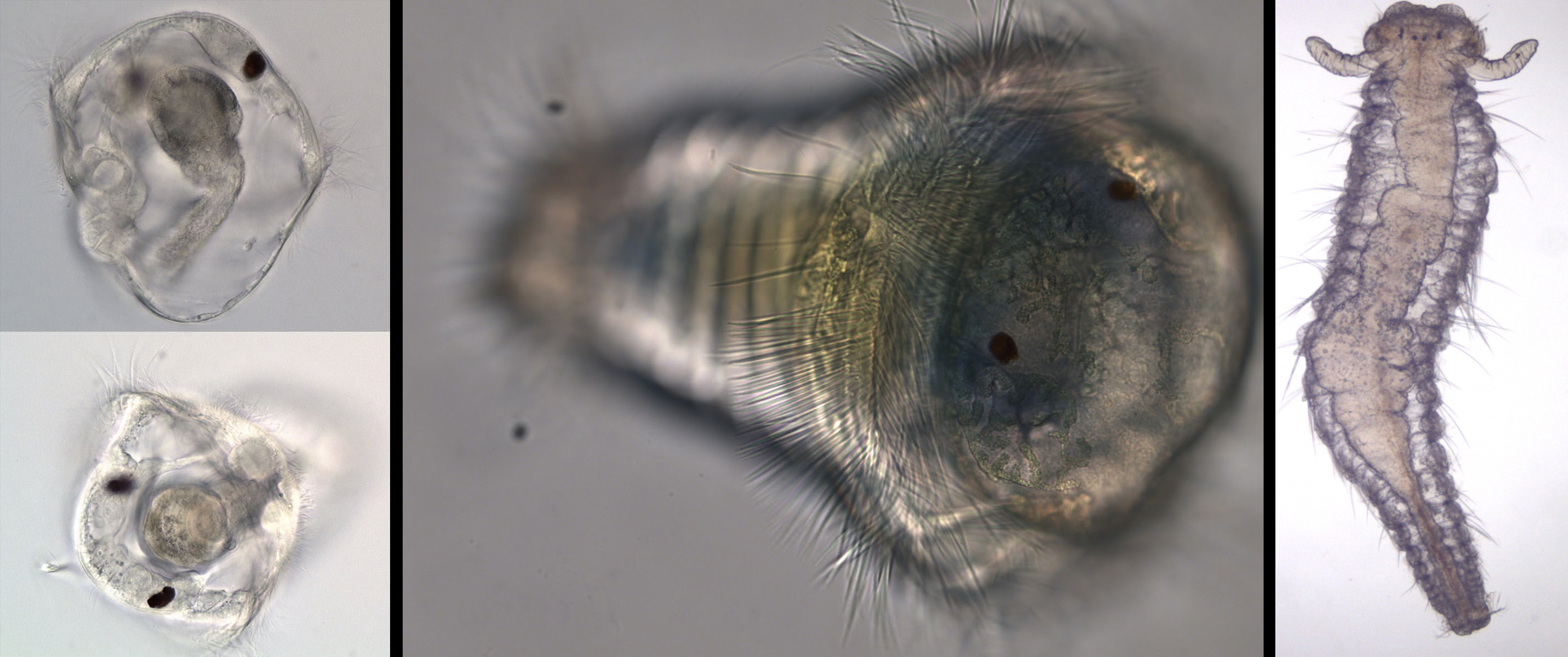

No matter the approach, the goal is the same: to make baby worms! Believe it or not, polychaete babies (called trochophore larvae) are surprisingly cute. These blob-like little tykes have tiny eyes, a tuft of hair at the top of their heads and a fringe of hair called cilia around their middles that helps them move around. Aw, your baby is so...hairy?

The larvae progress to the metatrochophore stage, where they begin to develop body segments, and then to the nechtochaete stage, where they start to look like real worms. This is the last step before they settle as adults. Photos by students at Oregon Institute of Marine Biology. Left top and bottom: trochophores, by Lisa Ziccarelli; Center: metatrochophore, by Jonathan Gienger; Right: nechtochaete, by Vickie.

Attachment parenting

When it comes to parental care, worms are generally thought of as hands-off (legs-off?), but some are actually nurturing moms that do their best to help their offspring get a head start in the world. Female worms in the family Spionidae lay orange eggs in capsules, which they adhere to the insides of their tubes. There they can be safe until they are old enough to wriggle away (see video of these babies in action at the top of this post)! The small syllid polychaete Exogone lets its young “hang around” until they mature. Illustration

Some syllid polychates take incubation a step further, allowing their bundles of joy to remain STUCK TO THEIR BODIES until they are fully grown (cue collective groan from all the moms out there).

The procreation strategies of polychaetes may run the gamut from the banal to the extremely bizarre, but they must be working, because the Puget Sound ecosystem is alive and crawling with their amazing benthic babies.

Critter of the Month

Dany is a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.