Live Pacific sand dollars at the Monterey Bay Aquarium look almost fuzzy. In calm water, you often see them standing up on one end. Photo by Chan Siuman, Wikimedia Commons.

Dollars to doughnuts

Sand dollars are echinoderms, like their spikier cousins, the sea urchins. In life, they share similar shades of purple, green, dark brown or black... but instead of the signature urchin dome-shape, sand dollars are squashed flat as pancakes. In other parts of the world, they are even called biscuit-urchins, sand-cakes, and sea-cookies. Now excuse me while I grab a pastry and put on the Great British Baking Show!

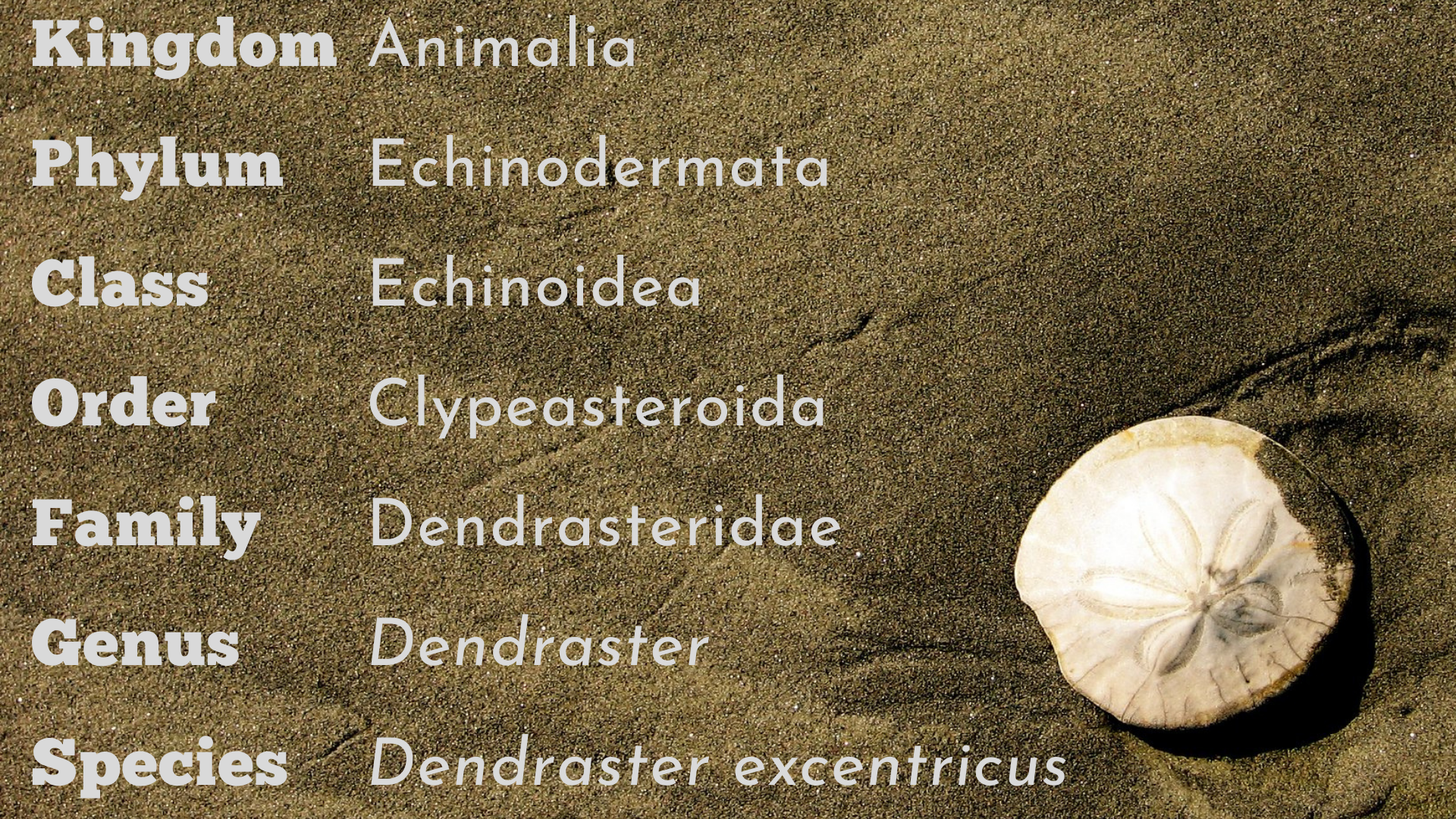

Here in the States, someone thought that the round, sun-bleached skeleton, or test, of a sand dollar resembled a shining silver dollar, the original form of US currency. In Washington and Oregon, we have just a single species: Dendraster excentricus, the Pacific sand dollar or eccentric sand dollar. Eccentric refers to the off-center petal design on the top of the test, called the petalidium. The “petals” are made up of many small holes, used for respiration.

Hard disc

Pacific sand dollars don’t need much protection from predators, because not many animals enjoy munching on hockey pucks (although there are exceptions, including sea stars, the starry flounder, and the always-tenacious sea gull). A lucky individual can live for 10 years or more, growing larger (up to 8 cm) as it lays down growth rings on its skeletal plates. The next time you find a dead sand dollar, try counting the rings to see if you can tell how old it is!

Freebird

When you’re done counting, give the test a shake. Can you hear something rattling around inside? You might not find money in there, but there is most certainly treasure. Gently break it open to release the “doves.” These five bird-shaped pieces are actually teeth that interlock in living sand dollars and sea urchins to form a mechanism called Aristotle’s Lantern, located in the central mouth. Sand dollars funnel particles of food, including tiny crustaceans, diatoms, and detritus (dead organic matter), into this structure by pushing them along grooves on their undersides with their stubby spines.

Left: Broken sand dollar test with “doves"; photo by Photoholic1, CC BY-NC-ND. Right: A sand dollar’s underside shows growth plates, feeding grooves, and mouth; photo by Brikat20, Wikimedia Commons.

Sound as a pound

Pacific sand dollars live in the shallow water of the surf zone, so they must take care not to get carried away by the currents. In rough water, they lay flat or slightly burrowed into the sand, and delicate juveniles will even swallow large sand grains to weigh themselves down.

Sand dollars are able to move slowly by waving their spines or tube feet, and they love to move towards other sand dollars, because this enhances their chances at mating success. In some areas, they can be found in great densities, with many hundreds packed into a square meter of sand.

If you can’t take the heat, then… ?

A mass stranding of Pacific sand dollars on an Oregon Beach in August 2021; exact cause unknown. Photo by Seaside Aquarium.

Know when to hold ‘em

If being in hot water isn’t enough, sand dollars face the added pressure of being harvested for wedding decorations, craft supplies, and the tourist trade. A Google search for “dried sand dollars” brings up hundreds of listings for these perfectly bleached beauties, many of them collected live. If you strike it rich in live sand dollars while wading in the shallows, it may be tempting to take them home… but leaving them where they lie is a much better bet.

Critter of the Month

Dany is a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Dany shares her discoveries by bringing us a benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.