Anderson Lake, located south of Port Townsend, has been well known for its toxic algae blooms since 2007, when a dog died as a result of exposure to the lake’s water. The lake itself, surrounded by warning signs, is generally closed from May to October because of the health hazards associated with cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae.

According to Dr. William Hobbs, a senior environmental scientist with our Toxic Studies Unit, while the nutrient-rich lake has always been home to abundant cyanobacteria, it’s unlikely that it has always had such high levels of toxins .

Scientists from our Toxic Studies Unit, alongside partners from Oregon State University and Jefferson County, recently completed work that suggests the lake’s toxicity is a recent phenomenon — one likely linked to human activity.

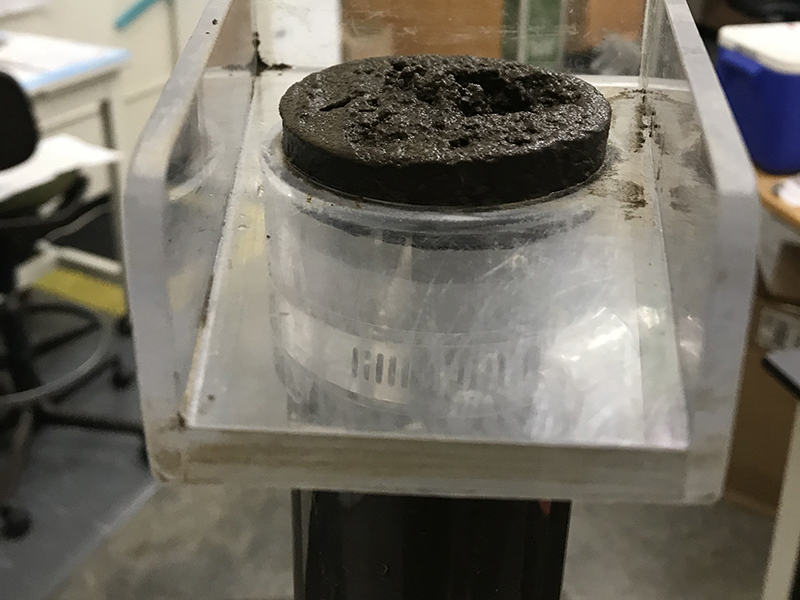

By taking core samples of sediment from the center of the lake bottom, scientists were able to get a look back in time to see when the increase in toxic algae blooms began.

“We go to the very center of a lake and push a tube into the mud,” Hobbs said. “That mud in the center of the lake gets deposited year after year. By analyzing the chemistry and biological remains in the sediment, it provides us with a history of lake water quality and lake algae communities.”

Hobbs said his team used radioisotopes to determine the age of the gathered sediment. Sediment at the bottom of the 73-centimeter core provided the scientists with about 300 years of information.

The team found evidence of cyanobacteria and other algae throughout the core sample, suggesting the lake has always had enough nutrients to support an abundance of cyanobacteria. However, analysis of DNA remains of the cyanobacteria in the sediment core indicated the main toxic strain of cyanobacteria has only been prevalent for the last three decades or so.

Hobbs said Anderson Lake has likely always been more nutrient rich than other lakes in the area because there are no big outlets in the lake to flush out nutrients. Because of that, the lake has always hosted an abundant algal community. Farming near the shore of the lake in the mid-20th century further added to the nutrient levels in Anderson Lake. Sediment from 1950s and 1960s reflected this, showing evidence of changes in the cyanobacteria population. The lake was possibly further impacted in the 1970s when it was stocked with rainbow trout. But it wasn’t until the mid-1990s that the modern toxic strain of cyanobacteria began to appear in the core sample.

Hobbs said while the core samples can indicate changes in the toxic blooms, we have to infer possible causes.

“It’s hard to pinpoint a particular mechanism,” Hobbs said. “We know there’ve been these changes to the ecosystems that coincide with the known history of the lake.” Cyanobacteria generally require plenty of nutrients and warmer waters than other algae.

Hobbs said the information gathered from this study can be used by lake managers to help determine which actions, if any, may be effective in controlling the lake’s cyanobacteria by limiting nutrient supply.

The Toxic Studies Unit has plans to conduct similar research in Spanaway Lake, Pierce County this year. Hobbs said it will be interesting to determine if the cyanobacteria there also pre-date human activity or whether the development of the shoreline had an impact on cyanobacteria presence.