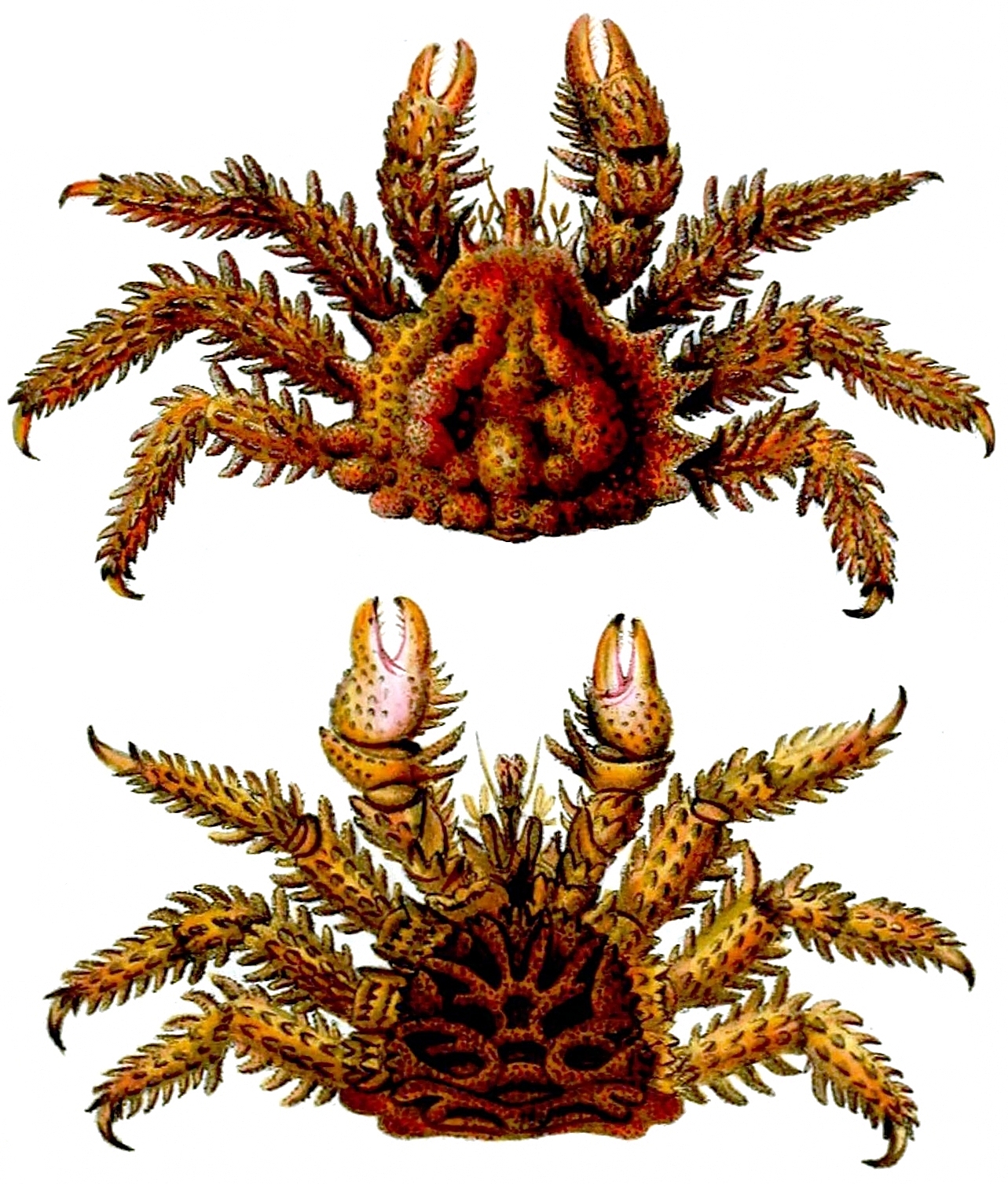

Is this critter an alien? Because it's abducted my heart. Heart crab from Alaska; photo courtesy of Erin McKittrick.

This National Singles Awareness Day Valentine’s Day, we bring you a first for our blog — a coy critter known to occur in Puget Sound, but that we have never crossed paths with in over 30 years of sediment sampling. As rare and wondrous as true love itself, the heart crab maintains a quiet existence, delighting the hearts of those lucky enough for a chance encounter.

Wearing your heart on your shell

Everyone knows the heart crab’s famously huge and delicious relative, the Alaskan King Crab (yes, the one from Deadliest Catch). While the humble heart crab doesn’t grow as impressively large, it has a distinctive adornment on its 4-inch carapace, or shell, that helps it stand out from the crowd: an upside-down orange heart made up of hard bumps called papillae. Add legs covered with thick, flattened spines, and you have the perfect species name: Phyllolithodes papillosus, from the Greek phyllo (leaf) and lithos (stony). The underside of this heart crab

Tender-hearted

Don’t let the prickly appearance fool you… underneath all those spines, the heart crab is a real softy. Its family members are descended from hermit crabs, and retain some of the hermits’ trademark softness. Have you ever seen a hermit crab without its borrowed shell? Take my word for it — their twisted, sad little bodies do NOT look good naked. The heart crab’s design is a vast improvement, but it still has its own version of the Death Star’s thermal exhaust port: squishy spots weakening the plates of armor on its abdomen. This heart

Harden my heart

Unlike hermit crabs, these crabs occasionally have to molt, or completely shed their shells, in order to grow, which leaves them extra soft and vulnerable. Freshly molted heart crabs are sometimes observed by divers sheltering under the appropriately-Valentine’s-hued crimson anemone, Cribrinopsis fernaldi. Perhaps the anemones’ stinging tentacles ward off hungry predators like the cabezon (a large species of sculpin native to the West Coast), until the crabs' new shells can harden.

You are my rock

When not hanging out under anemones, heart crabs can be found in fast-moving water as deep as 183 meters, especially where there are lots of rocks. Their unequal claws (another hermit crab throwback) serve the dual purposes of scraping rock-encrusting animals like sponges and ascidians, and crushing harder prey like sea urchins. Left: A heart crab clings to an encrusted rock. Center: A heart crab rests in a bivalve shell. Right: A juvenile heart crab has lighter coloration than adults. Photos courtesy of Erin McKittrick.

This preference for rocky depths is probably why most people don’t see heart crabs on Puget Sound beaches, and why we never catch them in our grabs. Juveniles are sometimes found intertidally (look for white crabs with purple or orange markings), but the general consensus among naturalists is that these animals are an uncommon sight to behold. Aorta tell you how pumped we would be to finally come across a heart crab, but for now we will just have to be content with the thrill of the chase!

Critter of the Month

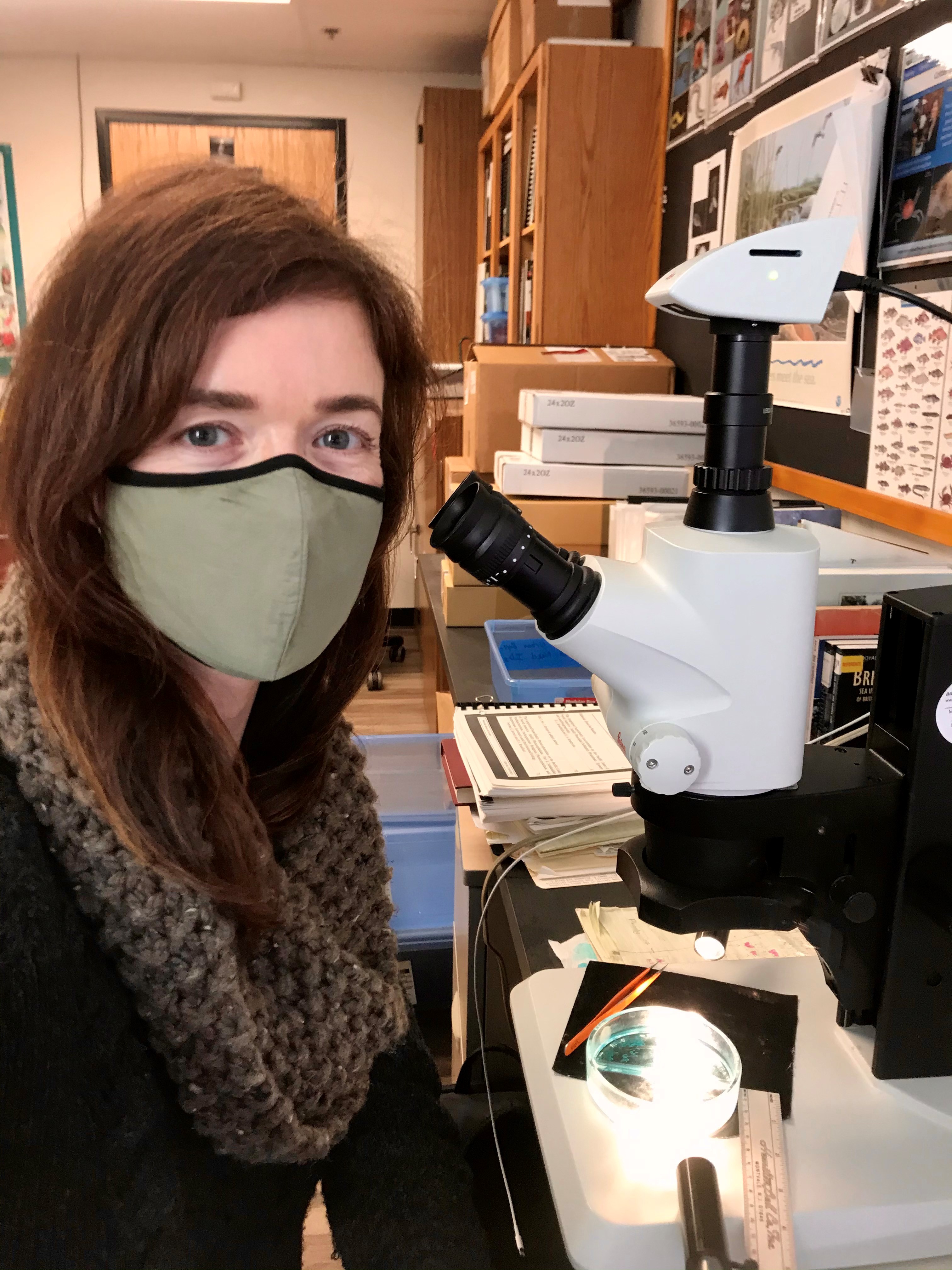

Dany is a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Dany shares her discoveries by bringing us a benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.