Sometimes you feel like a nut; sometimes you don’t! We hope you’re hungry, because we are just nuts about this month’s group of critters — the peanut worms. A peanut-shaped juvenile Golfingia sp. with introvert retracted.

Unsolved mysteries

These animals are commonly called “peanut worms” because some have the general shape of peanuts (although we think cashew worms would be more fitting). They actually aren’t considered worms at all, at least not like the marine segmented worms (polychaetes) in the phylum Annelida.

Peanut worms belong to the phylum Sipuncula (sy-PUN-kyoo-lah), meaning "little tube or siphon.” Recent genetic work, however, suggests that they might actually belong within, or closely related to, annelids. Like many taxonomic mysteries, this one remains to be solved!

Body language

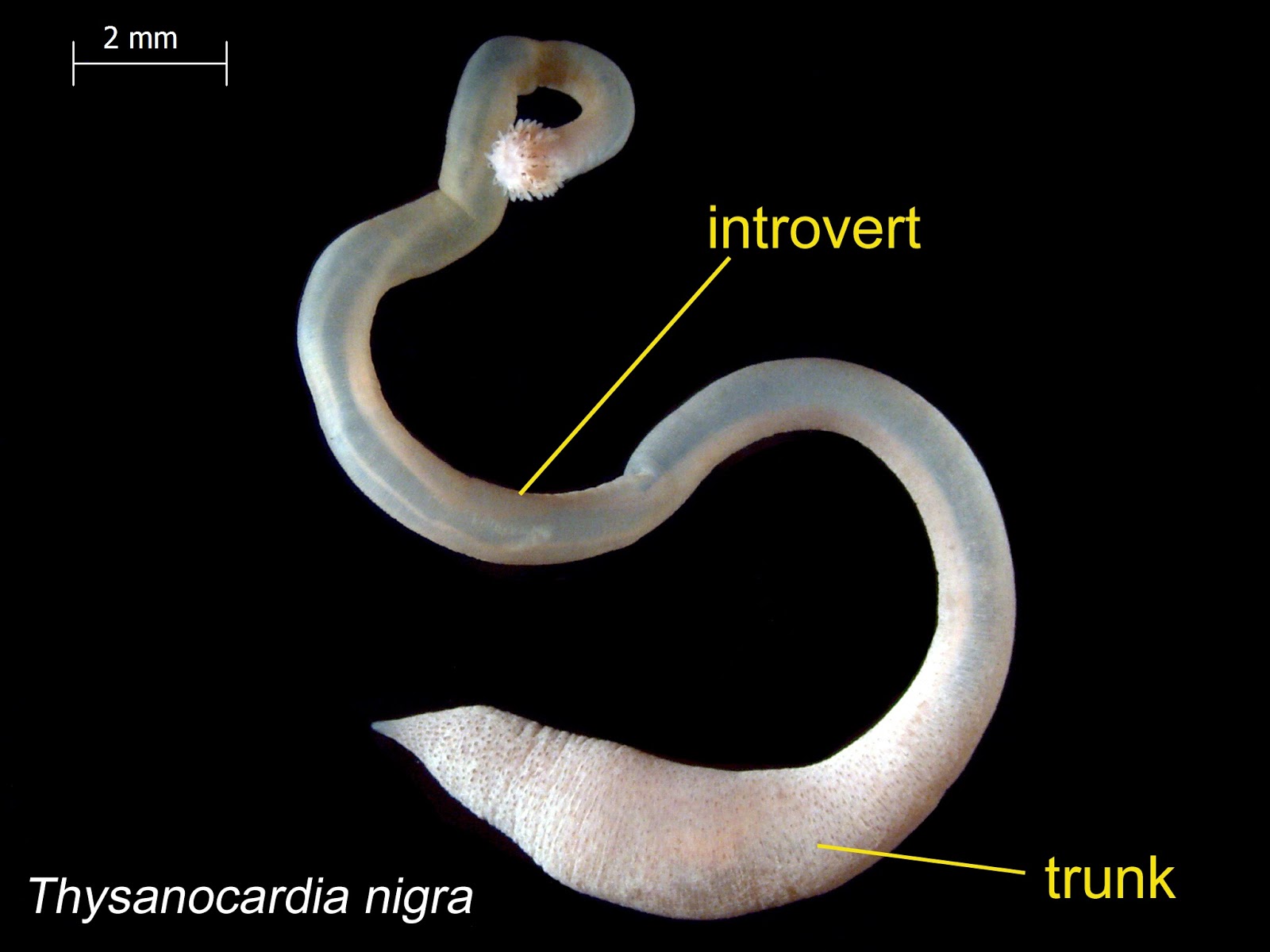

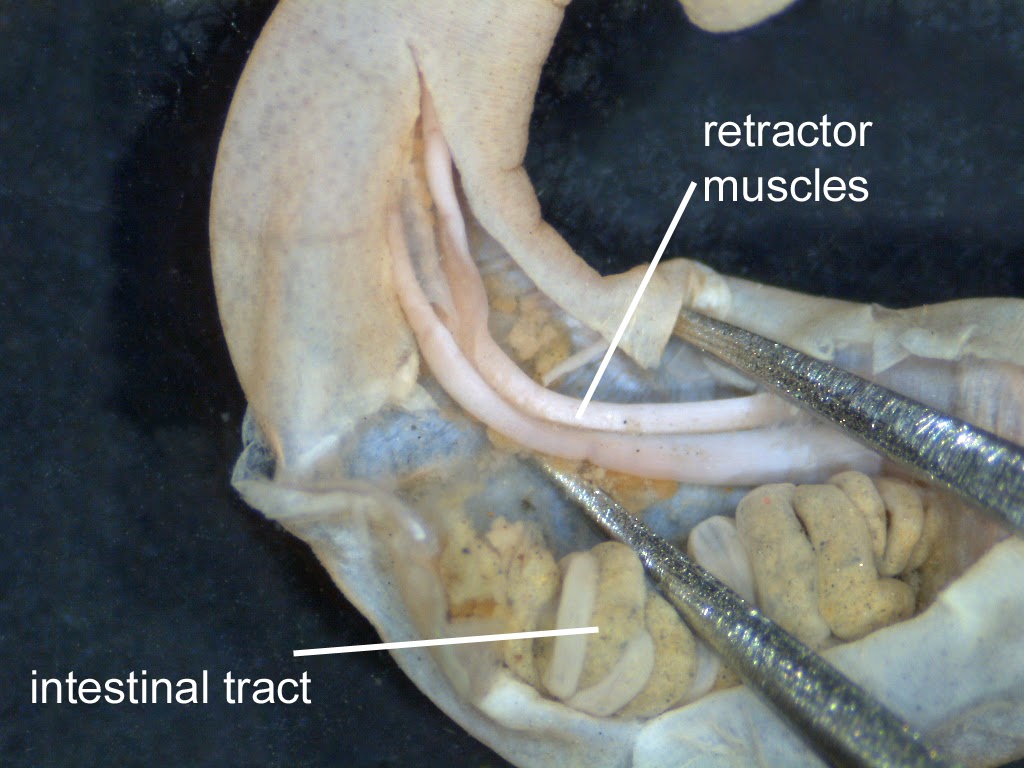

A dissected Thysanocardia nigra specimen with internal structures exposed

A good nut is hard to find

Sipunculans are exclusively marine, with most species living in shallow water (we have collected themfrom depths ranging from two - 270 meters). Our Puget Sound species grow to be just a few centimeters long, but some species can reach half a meter in length. Now that’s one big peanut! Phascolosoma agassizii

Although over 300 species have been described worldwide, the diversity of this group has been poorly studied, so there could potentially be more out there just waiting to be discovered. Before you decide to go out

Working for peanuts

Some species of sipunculans turn their noses up at pre-made burrows and prefer to build their own by boring into hard substrate (although scientists aren’t sure how they accomplish this with their soft, squishy bodies). We might say this makes these sipunculans boring brown blobs (see what we did there?!), but they are actually very important to the ecosystems they inhabit. All this boring and burrow-making helps to break down rocks and reefs into rubble which is used as a habitat by other organisms. Tentacles at the tip of the introvert of Thysanocardia nigra, the Smooth Brown Peanut Worm.

Sipunculans also play a crucial role in marine food webs. Some species use their tentacles for filter feeding, some ingest sediment and prey collected with their tentacles, and some species use their introvert hooks to scrape organisms off rocks. However, most are deposit feeders, eating detritus (particles of organic matter from decomposing plants and animals) and passing those nutrients back up the food chain as they are eaten by predators.

Tough nut to crack

Speaking of predators, there are plenty of fish out there that might like to eat a nice juicy peanut-shaped critter! Fishermen have been known to use sipunculan worms as bait, though mostly the larger sand-dwelling species. Sipunculans don’t have a lot of defensive strategies to protect themselves from a fish attack, but they can retract their introvert when disturbed. This is when they most resemble peanut shells, and how they look when we first see them in the grab samples on the boat.

Peanut butter jelly time

A bowl of sea worm jelly. Photo courtesy of Frank Kasell, www.chinesestreetfood.com.

Sea worm jelly is prepared by boiling the sipunculans, which releases a gelatin-like goo into the water. The whole concoction is then poured into molds and allowed to set. Apparently the jelly doesn’t have much flavor besides the soy sauce, oils, and spices added to it — but we’re happy to remain blissfully ignorant on that point!

Critter of the Month

Our benthic taxonomists, Dany and Angela, are scientists who identify and count the benthic (sediment-dwelling) organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see in order to understand the health of Puget Sound and detect changes over time.

Dany and Angela share their discoveries by bringing us a Benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.