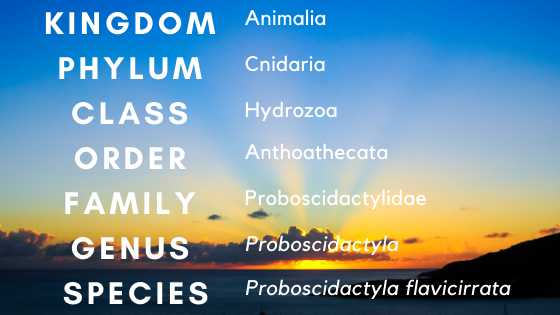

Double life

The “secret identity” of the two-tentacled hydroid, Proboscidactyla flavicirrata, is an adorable jellyfish-like medusa.

Which came first — the polyp or the egg?

Hydroids know a thing or two about new beginnings. The stationary colonies of polyps actually reinvent themselves, reproducing asexually by budding off itty-bitty jellies called hydromedusae. The two-tentacled hydroid’s hydromedusae are free-living and much smaller than true jellies — their round “bells” only grow to a diameter of 10 mm. I made this rudimentary figure of a hydroid life cycle and I’m super proud of it.

The sexual reproduction part of the life cycle begins in the medusa’s gonads (located in the central yellow blob called the manubrium). Hydroid colonies are sex-specific, each budding off only male or female hydromedusae, which produce either sperm or eggs. These get released into the water column, and after fertilization, develop into hairy planula larvae that eventually settle to form new colonies.

Living on the edge

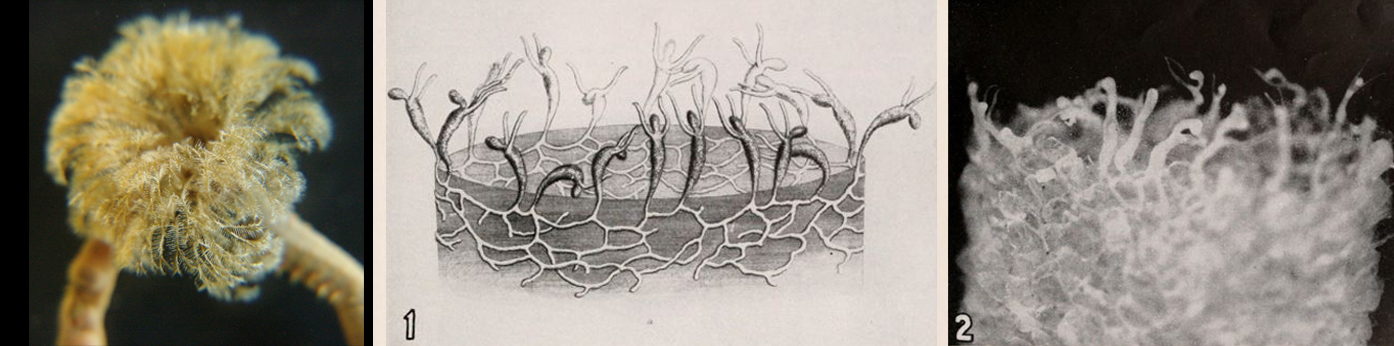

While the hydromedusae and planulae are out adventuring in open water, the parental colony is also living on the edge — literally. Two-tentacled hydroid polyps (which bear a striking resemblance to waving figures or dancers) shun the rocks and pilings that many hydroids choose for settlement. Instead, they prefer the openings of sand-grain tubes built by the sabellid family of marine segmented worms (polychaetes), commonly known as fan worms. Left: Tentacles of Schizobranchia insignis, a host worm. Photo by Dave Cowles, wallawalla.edu. Middle and right: illustration and photo of hydroid attached to tube. From Hand and Hendrickson

The hydroid’s swimming planula larvae scoot around until they are caught up in tiny currents created by a fan worm’s tentacles. The planula then attach by firing stinging cells called nematocysts into the tentacles, and get brushed onto the tube rim as the worm retracts. Metamorphosis into a polyp takes about 24 hours.

Taking root

A worm’s tube might sound like a hazardous place to put down roots, or in a hydroid’s case, a network of connected fibers called hydroriza. But the planula has chosen its home strategically, and intends to stay there. As the worm grows and makes its tube longer, the base of the hydroid colony elongates. This keeps the polyps lined up with the tube rim, in perfect position to benefit from a long-term symbiotic relationship with their host.

Den of thieves

Producing medusa buds is hard work, but the two-tentacled hydroid doesn’t have to worry about its fuel supply. When the colony needs food, the polyps simply reach out with their little arms (okay, tentacles) and steal right from the worm’s mouth. If that wasn’t bad enough, the polyps also steal and eat the worm’s eggs! Hydromedusae of Proboscidactyla flavicirrata. Photo courtesy of Dave Cowles, wallawalla.edu.

This symbiosis with the worm is so important to the hydroid that if you remove the tube from the equation (as researchers have done in laboratory experiments), the hydroid colony will start to restructure itself, absorbing some of its polyps and completely rethinking its feeding strategy. When the colony is reattached to a tube, it returns to its original form.

We humans could take a page out of the two-tentacled hydroid’s book. Despite our imperfections and broken resolutions, it’s never too late to be brand new.

Critter of the Month

Dany is a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Dany shares her discoveries by bringing us a benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.