Don't worry, worm shown above is not actual size; ice cream cone worms are only about an inch long!

Ice ice baby

Ice cream cone worms (belonging to the family Pectinariidae) are easily recognized by their distinct cone-shaped tubes that can be up to 5 cm (2 inches) long. Here in Puget Sound we find two species of these ice cold beauties — Pectinaria californiensis and Cistenides granulata.

Although both of these species are widespread throughout the Sound in depths up to 230 meters, Hood Canal is where we encounter them in the highest abundances — we can sometimes get over 30 of these critters in a single benthic sample!

Lashing out

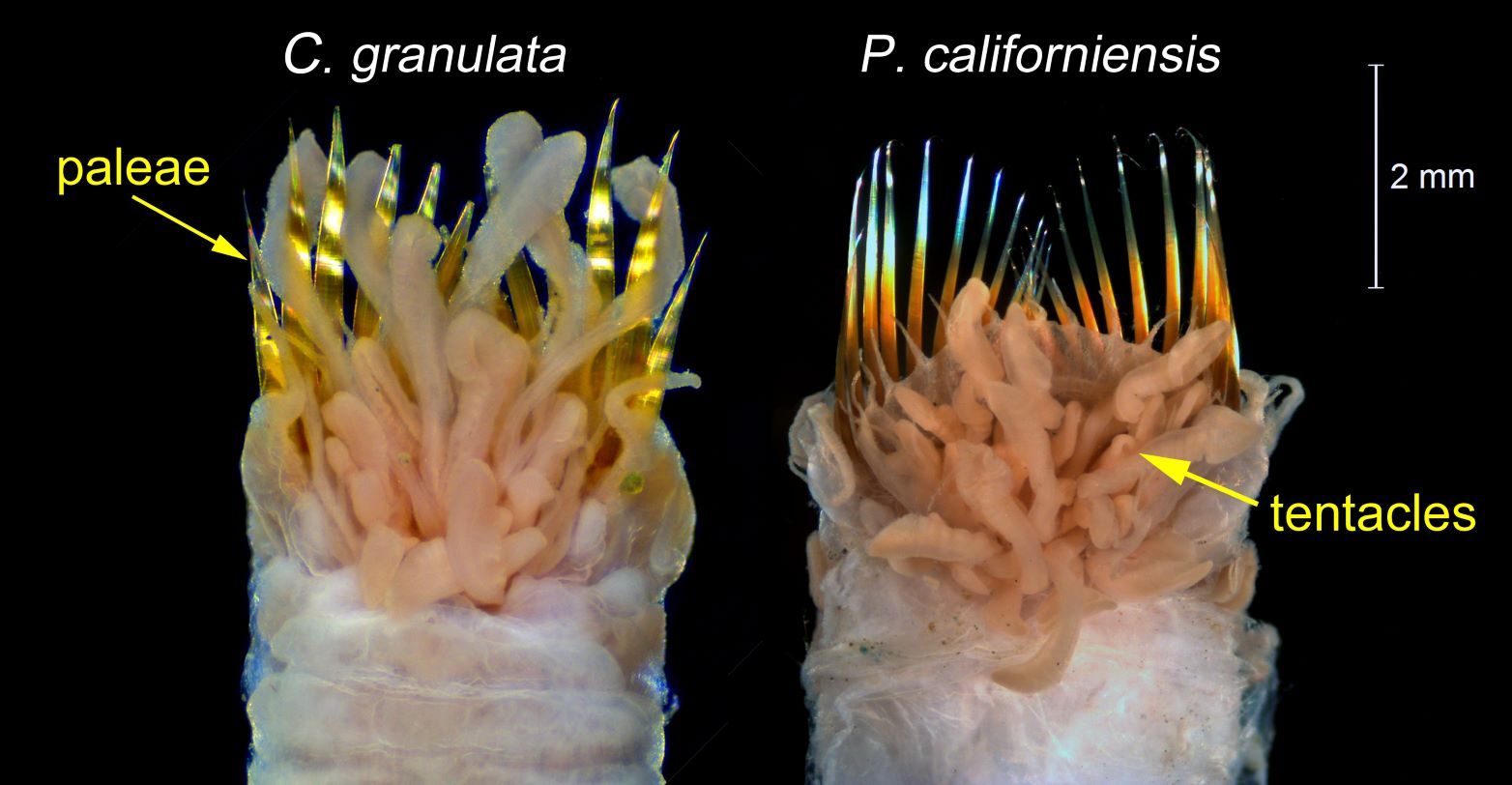

Another distinct feature that sets pectinariids apart is a pair of glistening “eyelashes” protruding from the tops of their cones. These spiky eyelashes are actually hardened hairs, called paleae.

The paleae may look pretty and delicate, but they serve a practical purpose — to help the worm burrow head-first into the sediment.

Everybody poops

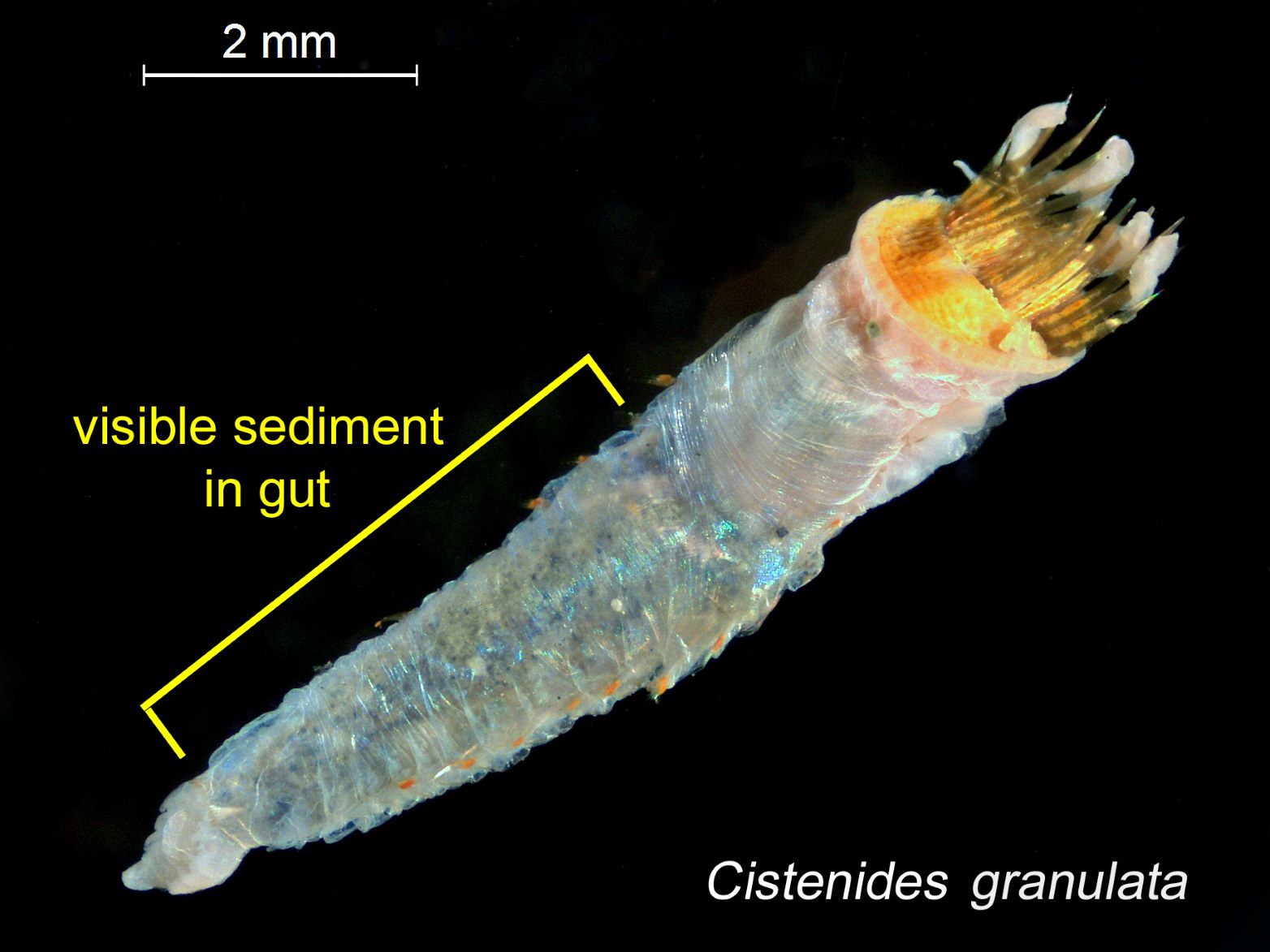

Ice cream cone worms spend most of their time face-down in the mud, with the pointy ends of their tubes turned upright sticking out just above the sediment’s surface. This allows them to use their tentacles (located near the paleae) to search around in the mud for large particles of sediment to ingest. A Cistenides granulata specimen, removed from its tube to reveal its translucent body with visible sediment inside

This strategy of picky eating is called selective deposit feeding. Anything the critter can digest that attaches to the particles gets absorbed by the worm’s gut. The sediment grains they can't digest basically go in one end and out the other. The passed material is called pseudofeces — meaning “false poop”.

It can take up to six hours to make its way through the worm’s body and out the open end of the cone. If you were to observe a living ice cream cone worm without its cone, you would be able to see this whole process through its translucent body wall.

Go your cone way

If you’re looking for ice cream cone worms, chances are you can find them in areas with a higher sand content (versus rock or fine clay). This makes sense when you think about how they build their cones.

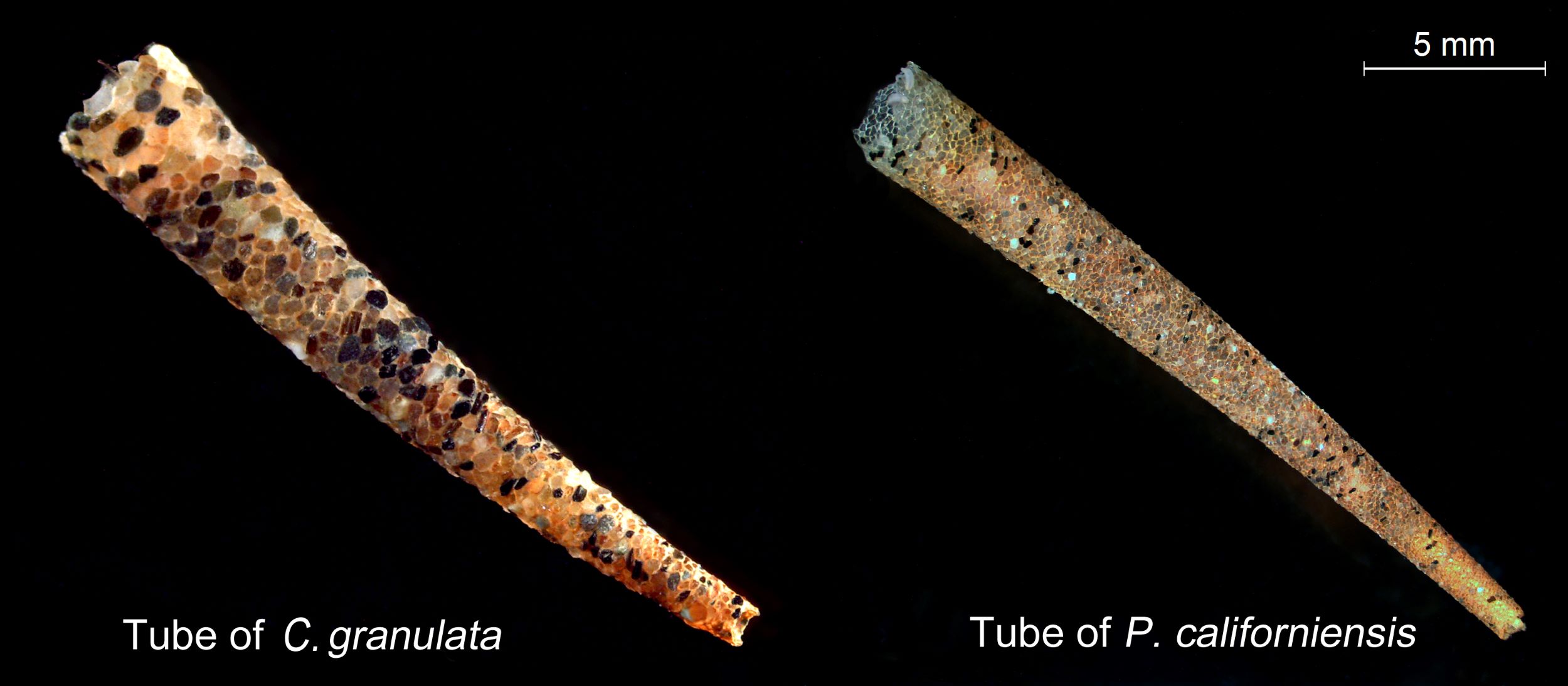

Pectinariids construct their cones by reaching out with their tentacles to collect sand grains, shell pieces, or other small particles. These grains are tightly placed together in layers, giving the cone a smooth but speckled appearance, almost like a colorful stained glass window or a tile mosaic. The cone protects the critter, housing the animal’s soft, fleshy body in a speckled coat of armor.

A worm’s place is in the cone

A comparison of the tubes of C. granulata and P. californiensis shows the difference in preferred grain size between the two species.

For example, P. californiensis chooses fine sediment granules for its straight, delicate tube, while C. granulata prefers coarser sediment for its robust, slightly curved tube. If the worm doesn’t have an intact cone, it can still be identified by the color and shape of its paleae — P. californiensis has copper-colored paleae with fine tips, and C. granulata’s are golden-colored, with blunt tips.

C. granulata