Let’s get “straight to the point”: this month’s animal mish-mash is “right on target” to be named one of the strangest creatures roaming Puget Sound.

Weird and wonderful

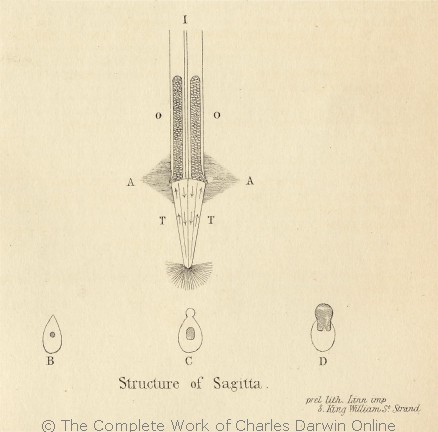

Named for the Greek chaite (“bristle”) and gnathos (“jaw”), the arrow worms, or chaetognaths (pronounced “KEE-toe-naths”), are a bizarre example of Mother Nature’s quirky sense of humor. Even Darwin marveled at their weirdness when he observed them from aboard the HMS Beagle in 1832. With their Frankenstein-esque combination of slender worm-like bodies and fishy tail fins, they do resemble tiny living arrows gliding through the water. Charles Darwin drew these illustrations for a paper that included his first observations of arrow worms. Source: Darwin Online.

What are arrow worms, exactly?

Well…they aren’t worms OR fish. Scientists used to believe that this phylum had no living relatives, but a new study places them with two other obscure phyla in a group called the Gnathifera, meaning “jaw-bearer.” More on those jaws later!

Easy tiger

While there are only about 120 species of arrow worms worldwide, they are incredibly abundant in every ocean on Earth. This is very good news for marine food webs, in which they play an important role as primary predators, and very bad news for copepods, their favorite prey. Nicknamed (rather ominously) the “Tigers of the Zooplankton,” arrow worms are voracious carnivores that eat everything in sight.

Eye of the tiger

When an arrow worm senses that a tasty copepod (or small fish, or other arrow worm, etc.) is nearby, it sneaks up — easy to do when you’re completely transparent. It has eyes that may help it see light, but it relies more on sensory hairs along its body to detect the movements of a future meal. The grasping head spines reach out in a flash, crushing the prey and pulling it into the jaws, which can project forward like a snake’s. As a secondary weapon, the tooth-lined mouth can inject a potent venom produced by bacteria in the gut. This close-up of the head of the arrow worm Sagitta makes me so thankful I am not a copepod. Photo by Zatelmar; Source: Wikipedia Commons.

There is a price to pay for being such an efficient hunter: arrow worms are a prized food of whales, fish, birds and squids, passing all that rich copepod goodness up through the higher trophic levels.

Moving target

Arrow worms’ bodies are designed for slicing through the water, because they are constantly on the move. Tracking the migratory habits of the copepods, they swim to the surface at night and descend toward the sea floor during the daylight hours, in a pattern called diel vertical migration. In very deep water, this can mean a serious journey undertaken every single day. In cold oceans like the Arctic, arrow worms can live for over two years…that means making 730+ round trips that might be hundreds of meters each way! No wonder they need so many snacks for the road.

Under the hood

The arrow worm has tricks that help it excel in its mobile lifestyle. In addition to a streamlined body shape, it has a “swimming cap”: a hood-like flap of skin on its neck that can be drawn up to cover the entire head, spines and all. It swims using a rapid darting motion, produced by flicking the large caudal fin on the tail. The side fins help with stabilization and allow the animal to kick back and float until it’s ready for the next burst of speed.

Twist of fate

You can easily see the fishy caudal

Cupid’s arrow

Arrow worms are hermaphrodites, meaning that they have both male and female reproductive organs in their bodies. Despite having the ability to fertilize themselves (which does occasionally happen — yikes!), most mate with other individuals. During mating, each arrow worm places a bundle of sperm onto its partner’s neck. The sperm swim down the body until they get to the tail, where a pair of pores lead to tubes with the developed eggs inside. Fertilized eggs are released into the water and left on their own to grow into tiny — and hungry — swimming arrows.

Critter of the Month

Dany is a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Dany shares her discoveries by bringing us a benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.