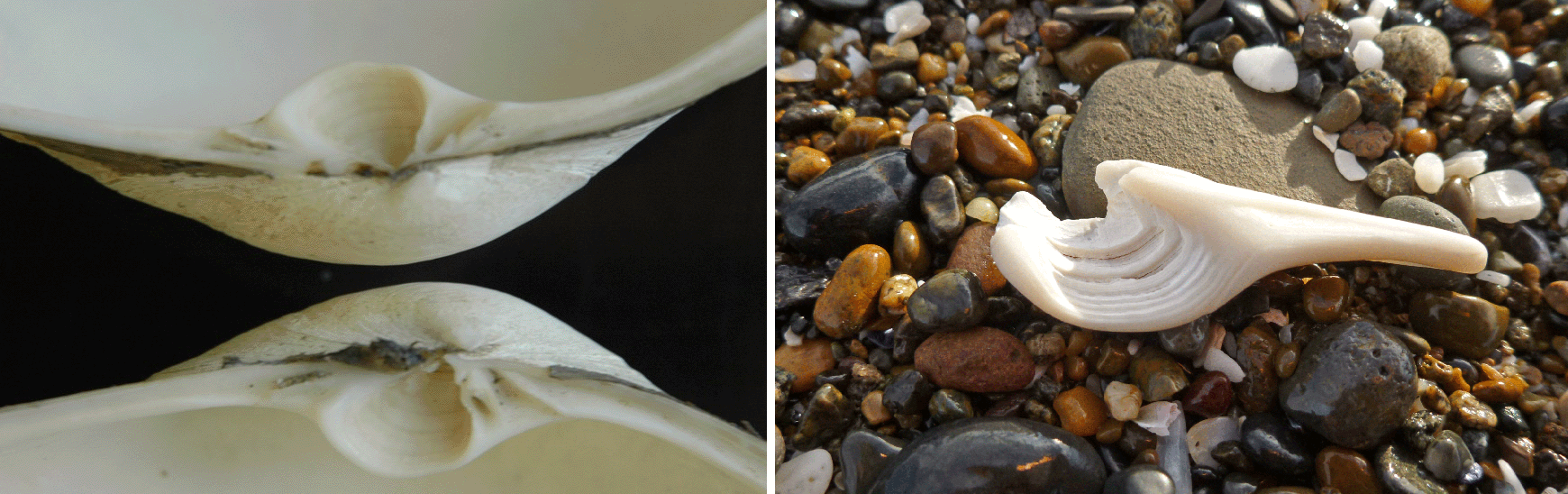

Nope – it’s not a geoduck. Both of these are gaper/horse clams. Left: Photo by Dana Brown, flickr; Right: Photo by Dave Cowles, wallawalla.edu.

Nothing says “summer” like digging for steamer clams in Puget Sound. But the Pacific Northwest is known for its B.O.U.S.s (Bivalves Of Unusual Size), and if you dig deep enough, you may unearth a monster instead of a manila.

The gaper clams (a.k.a. horse clams) are one such behemoth. Instead of being viewed as a prize, however, they are often met with disappointment. Geoduck hunters, don’t despair — the humble gaper is a treasure in its own right.

Mind the gape

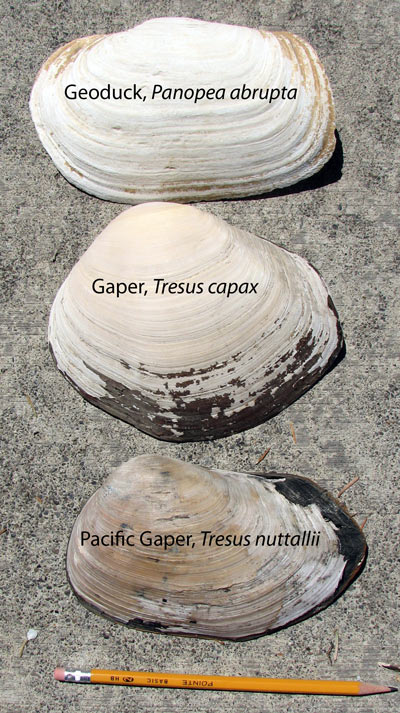

The quality of gaper clams might be up for debate, but no one can dispute the quantity. A gaper’s oval-shaped, chalky-white shell can grow to a length of about eight inches (about the same as a geoduck). Two species of gapers occur in Puget Sound: the fat gaper or Alaskan gaper (Tresus capax), and the less-common Pacific gaper (T. nuttallii), which has a narrower shell. Both species have a wide gape at one end of their shells to accommodate large tube-like siphons, used for water exchange. Photo by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Note that the correct scientific name of the geoduck

Burial grounds

The siphons of gaper clams and geoducks are too large to be completely pulled inside their shells, so both must bury themselves deeply to avoid being chomped by predators like Dungeness crabs, moon snails, sea stars, and gulls.

Gaper clams aren’t as strong diggers as their “better-at-everything” cousins the geoducks, but individuals can still be found up to four feet deep, with a typical burial depth of 12-16 inches (about the same depth as butter and littleneck clams). They prefer intertidal or shallow subtidal mud or sand in protected bays, but you can sometimes find them on the outer coast.

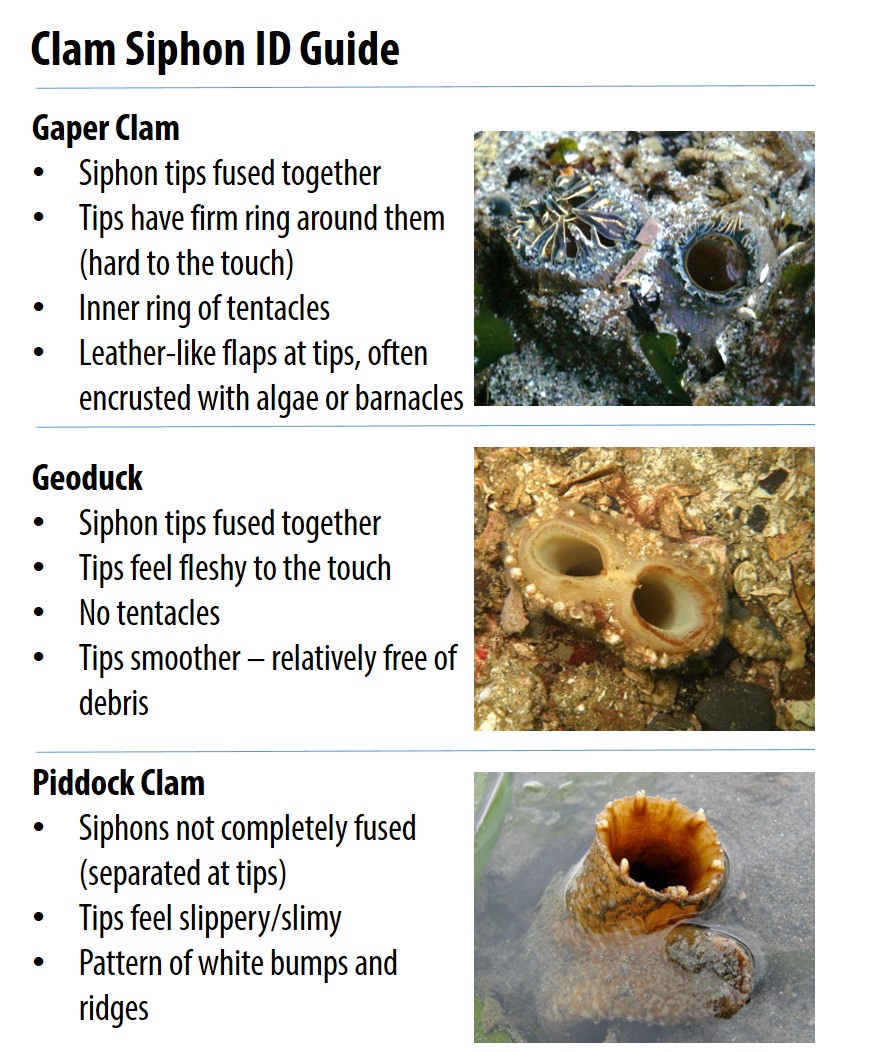

You might see these bivalve siphons at low tide on Puget Sound beaches. Photos by Minette Layne, Wikimedia

Pro (siphon) tip

Gapers and geoducks share another similarity: their two siphons are fused together into a “neck” that protrudes out of the sediment (the tips of which occasionally squirt unsuspecting passers-by with water at low tide). If you look closely at the siphon tips, you can tell gapers, geoducks, and other large clams apart… no digging required!

A gaper clam’s siphon is like a giant set of straws, one for sucking in water at high tide to filter for plankton and other food bits, and the other to pump the unwanted stuff out. Large, open siphons also mean easy access for unwelcome guests, including at least three different species of pea crabs, which live inside the gaper clam’s tissues.

You’re HOW many annuli old?!

While not as long-lived as geoducks, gapers can live up to 29 years, maturing at age three to five. Each year, the clam lays down a growth ring called an annulus on its chondrophore, a cavity near the hinge of its shell. The gaper clam’s distinct, thick chondrophore is recognizable long after the rest of the shell has been tumbled away by beach surf. Simply count the rings, and now you, too, are a gaper clam aging expert, sure to impress all your friends at parties! Left: A gaper clam hinge shows the deep chondrophore in the middle. Photo by Dave Cowles, wallawalla.edu. Right: A chondrophore is all that remains of a gaper shell. Photo by minustide, flickr.

Can you dig it?

Gaper clams were harvested by early native Americans on the west coast, and they are dug both recreationally and commercially today (more in Oregon than in Washington… don’t ask me what that’s about). Supposedly they are a little tougher and not as delicate in flavor as geoducks, but the word on the street is that they make great fritters or chowder.

That’s a clam shame

Unfortunately, some folks still consider gapers to be “trash clams,” either using them as crab bait or leaving them littered on the beach after clam digs. Adult gapers can’t rebury themselves, and without the pressure of the mud to hold their large valves together, they soon die. Diggers need only place them back into their holes with the siphons pointing up, so they can live to gape another day.

This story wouldn’t be complete without a disclaimer: before you dig for any kind of shellfish, make sure you have the proper permits and that the beach you choose is open and safe for harvest. Happy clamming!

Critter of the Month

Dany is a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Dany shares her discoveries by bringing us a benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.