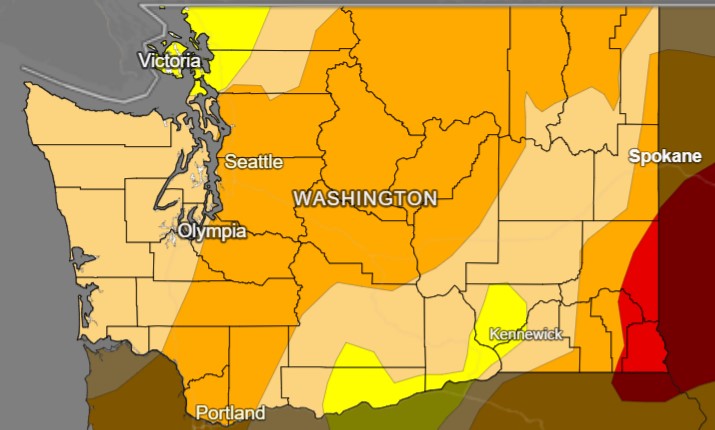

This U.S. Drought Monitor map shows most of Washington is in a state of moderate or severe drought. Asotin, Garfield, and Whitman Counties are now considered to be in a state of “extreme drought”. Image Credit: Brian Fuchs, National Drought Mitigation Center

Three Washington counties have been designated primary natural disaster areas by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Asotin, Garfield, and Whitman Counties are now considered to be in a state of “extreme drought” according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

The new designation makes farmers in primary and neighboring counties eligible to apply for federal Farm Service Agency emergency loan assistance.

These counties were not included in the state’s drought declaration due to differences in methodology.

The Washington Department of Ecology issued an emergency drought declaration on April 8 this year, then expanded the declaration to include more counties on June 5. Since then, conditions have continued to deteriorate. In Washington, a drought is declared when there is less than 75% of normal water supply and there is undue hardship for people or the environment.

The hardship requirement is one of the key differences between state and federal drought designations. A state drought declaration also enables Ecology to offer emergency drought relief grants to Tribes and eligible public entities, but not to individual farmers.

Rapid decline in conditions in eastern Washington

Whitman, Garfield and Asotin are now under a primary federal drought designation as portions are now in D3, or “extreme drought” status on the U.S. Drought Monitor. A federal drought designation occurs when a county experiences a drought level during the growing season of D3 “extreme drought” or D4 “exceptional drought” on the US Drought Monitor, or D2, “severe drought”, for eight or more consecutive weeks.

Currently no other part of the state is in D3 status. Most of the Cascade Mountain and northeastern parts of the state are in D2 status.

Eastern Washington has been hit especially hard by drought this summer. Franklin County and Grant County received no precipitation at all in June, making this the driest June on record for those counties. Adams County experienced its driest June on record with only .01 inches of precipitation. The wettest county in eastern Washington was Pend Oreille, which experienced its fourth driest June on record with .8 inches of precipitation. Spokane, Garfield, Walla Walla, and Whitman Counties also experienced their driest Junes on record, each with less than one .25 inches of precipitation.

It's getting worse across the state

The Water Supply Availability meeting is a monthly gathering of state and federal water supply experts who discuss water supply conditions throughout Washington.

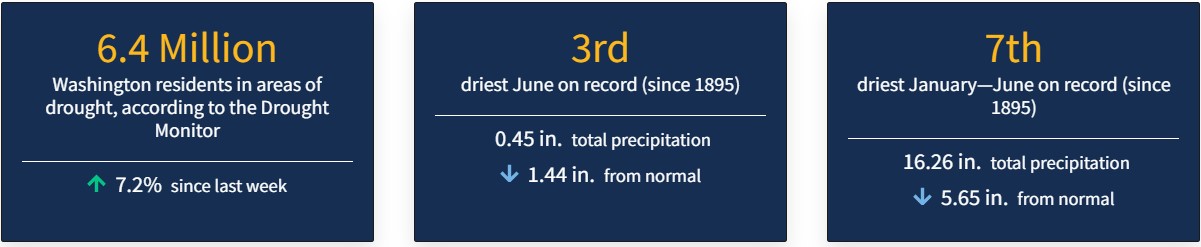

Since June 5, conditions throughout the state have rapidly deteriorated. With 23% of normal June precipitation, the state has just left the third driest and 10th hottest June on record.

The data from June does not tell the whole story. Drier than normal conditions have been more widespread across the state since January and have progressively deteriorated through spring. January through June was the seventh driest on record. April through June was the sixth driest on record.

Snowpack might continue to be an issue, if most of the snow weren’t already gone. Snowpack sites that historically had snow at the beginning of July were already melted out or well below normal melt by July 1. In the Nooksack area snow melted out 13 days earlier than normal. Easy Pass was projected to melt out 12 days ahead of normal. Brown Top melted out 19 days early, Lyman Lake 21 days early, and Corral Pass melted out 31 days early.

Soil moisture levels continue dropping with the worst moisture deficits occurring in the Lower Yakima Basin. This matters as soil moisture impacts the ability for any precipitation we do receive to be absorbed into the ground.

There’s little hope for relief any time soon. The Climate Prediction Center forecasts for July and August have a high probability of being warmer and drier than normal, even for summer in Washington.

Source: U.S. Drought Monitor

Report drought impacts

How has the drought affected you? To effectively plan for future droughts, we need to hear about your observations and drought impacts. This helps us understand impacts of drought conditions across the state this year. Submit your observations to the Condition Monitoring Observer Reports system. Developed by the National Integrated Drought Information System and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, CMOR reports are used to understand drought state wide and inform the Water Year impacts Assessment.