British Columbian Doto

The Northwest is known for the slugs and snails that thrive in the undergrowth of its damp, mossy forests. Critters like this also live under the sea, like Doto columbiana, commonly called the British Columbian Doto. This species was first discovered in British Columbia and has been reported as far south as Santa Barbara, California.

It's a nudibranch

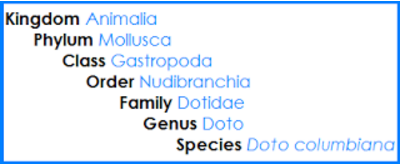

Classification of Doto columbiana

The British Columbian Doto belongs to a category of animals called nudibranchs (pronounced NEW-dih-bronks), often referred to as sea slugs. There are over 3,000 species of nudibranchs worldwide, but fewer than 20 species exist in Puget Sound.

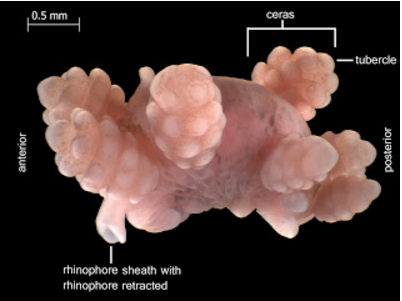

D. columbiana is a tiny critter, only reaching about 8 mm in length. Along the sides of its body are soft lumpy structures called cerata (plural for ceras) that look like clusters of grapes and function as digestive glands. The leopard-like coloration on D. columbiana can vary between individuals but generally consists of brown mottling throughout the body along with darker rings at the base of each grape-like tubercle.

Excuse me? My "antennae" are called rhinophores!

D. columbiana - profile of whole preserved specimen stained pink.

The antenna-like structures on the nudibranchs’ heads are called rhinophores. These are a type of chemo-sensory structure, allowing nudibranchs to sense the world around them. The word “rhinophore” comes from the Greek word “rhino,” meaning nose, which is appropriate since they function as an organ of “smell.”

However, while humans smell scents in the air with their noses, nudibranchs “smell” or detect scents that are dissolved in the sea water around them to find food. The rhinophores’ worm-like appearance makes them an easy target for predators, so they can be quickly retracted into a trumpet-shaped rhinophore sheath for protection.

You are what you eat

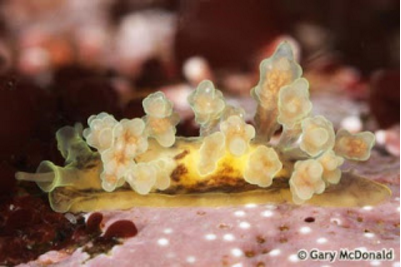

D. columbiana on a colony of the hydroid Aglaophenia

Nudibranchs are carnivorous and get their pigmentation, or colors, from the food they eat. Nudibranchs that eat brightly colored creatures are brighter too. In fact, many have brilliant bodies of intensely contrasting colors.

The British Columbian Doto is quite drab by comparison. D. columbiana eats hydroids (colonies of tinier critters called polyps, related to jellyfish) from the genus Aglaophenia. An Aglaophenia colony looks like a brown fern frond or feather plume, and these neutral colors are incorporated into D. columbiana’s body to help camouflage it from predators.

D. columbiana conveniently lives on what it eats as well, laying its eggs on the underside of the hydroid’s branches. When the eggs hatch, the young larvae have shells which disappear as the nudibranchs become adults.

Taxonomy troubles

Doto columbiana has a soft body that does not preserve very well.

D. columbiana, like many soft-bodied critters, does not preserve well. The colors can be lost and the shape can become distorted. Benthic taxonomists, the scientists who identify these small marine critters, have to look closely at features like the cerata and rhinophores to determine which critter they have collected.

Critter of the Month

Our benthic taxonomists, Dany and Angela, share their discoveries by bringing us a Benthic Critter of the Month. Dany and Angela are scientists who work for the Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants.

In each issue we will highlight one of the Sound’s many fascinating invertebrates. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role this critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr. Look for the Critter of the Month on our blog.