White bubble snail, Haminoea vesicula, on sea lettuce; photo by Gregory C. Jensen, iNaturalist, CC BY-NC-SA

Welcome to the Critter edition of “Weird Celebrations We Didn’t Know Existed!” Apparently the promise of spring makes people feel all bubbly inside, because March contains both National Bubble Gum Week (the 10th-16th) AND National Bubble Week (the 19th-26th). Not to be left out of the fun, this month’s Puget Sound invertebrate creature feature is the bubbliest of them all: the bubble snails.

Bubble burster

If you think these adorable “snails” look a bit sluggy, then you’re on the right track! The bubble snails are sea slugs rather than true snails.

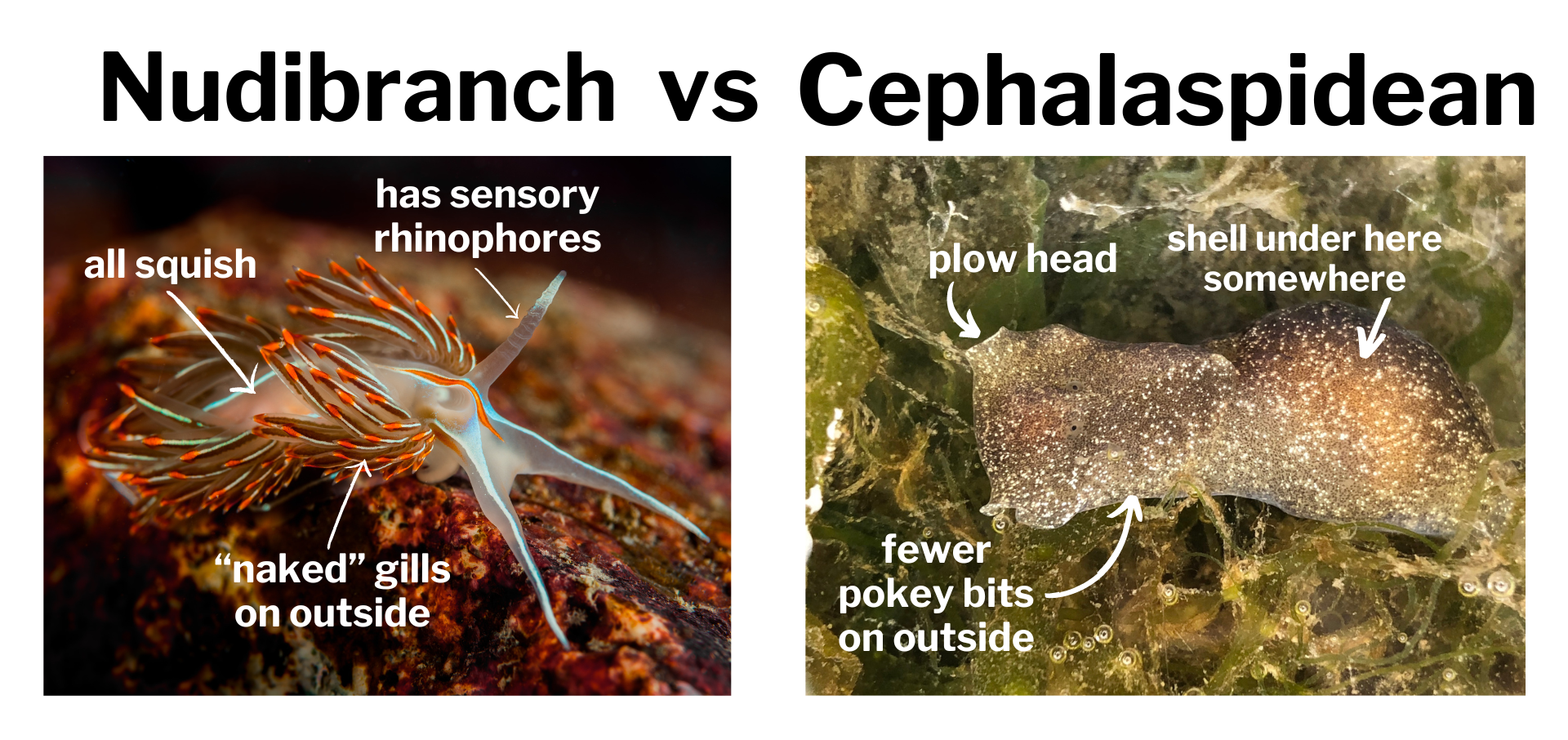

The phrase “sea slug” immediately makes me think of nudibranchs, those colorful and charismatic subjects of many a dive photo. But there are several kinds of sea slugs and not all of them are nudibranchs. Bubble snails belong to the order Cephalaspidea, most of which have an external shell that nudibranchs lack as adults. Collectively known as the “head shield slugs,” the cephalaspideans’ plow-like noggins allow them to burrow into the sand while diverting those pesky grains away from their most sensitive places.

Left: Northern opalescent nudibranch; Right: White bubble snail, photo by kelpadelpian, iNaturalist, CC BY-NC-SA.

Bubble boy

Life in a bubble might sound like the ultimate protection, but being bubble-bound doesn’t help much when your body is several sizes too large to fit completely inside. Rather, the bubble snail carries its delicate shell on its back, often concealed under wing-like parapodial lobes – extensions of the snail’s muscular foot. Bubble snails protect themselves from predators (including other sea slugs!) with camouflage or by staying safely buried.

Spring forward

When the weather begins to warm in the spring, bubble snails emerge from the sand to graze on algae and reproduce. The white bubble snail (Haminoea vesicula, Puget Sound’s most common species) can be found by the hundreds in eelgrass beds and on dock floats in the spring and summer months. The less common green bubble snail (Haminoea virescens) prefers rockier coastal habitats but can also be found in a few of Puget Sound’s protected bays. Both species leave behind masses of eggs in cheerful yellow or white coils.

Left: A white bubble snail is out and about, by maradg; Right: Egg mass on eelgrass, by kathawk. Both photos from iNaturalist, CC BY-NC-SA

Toil and trouble

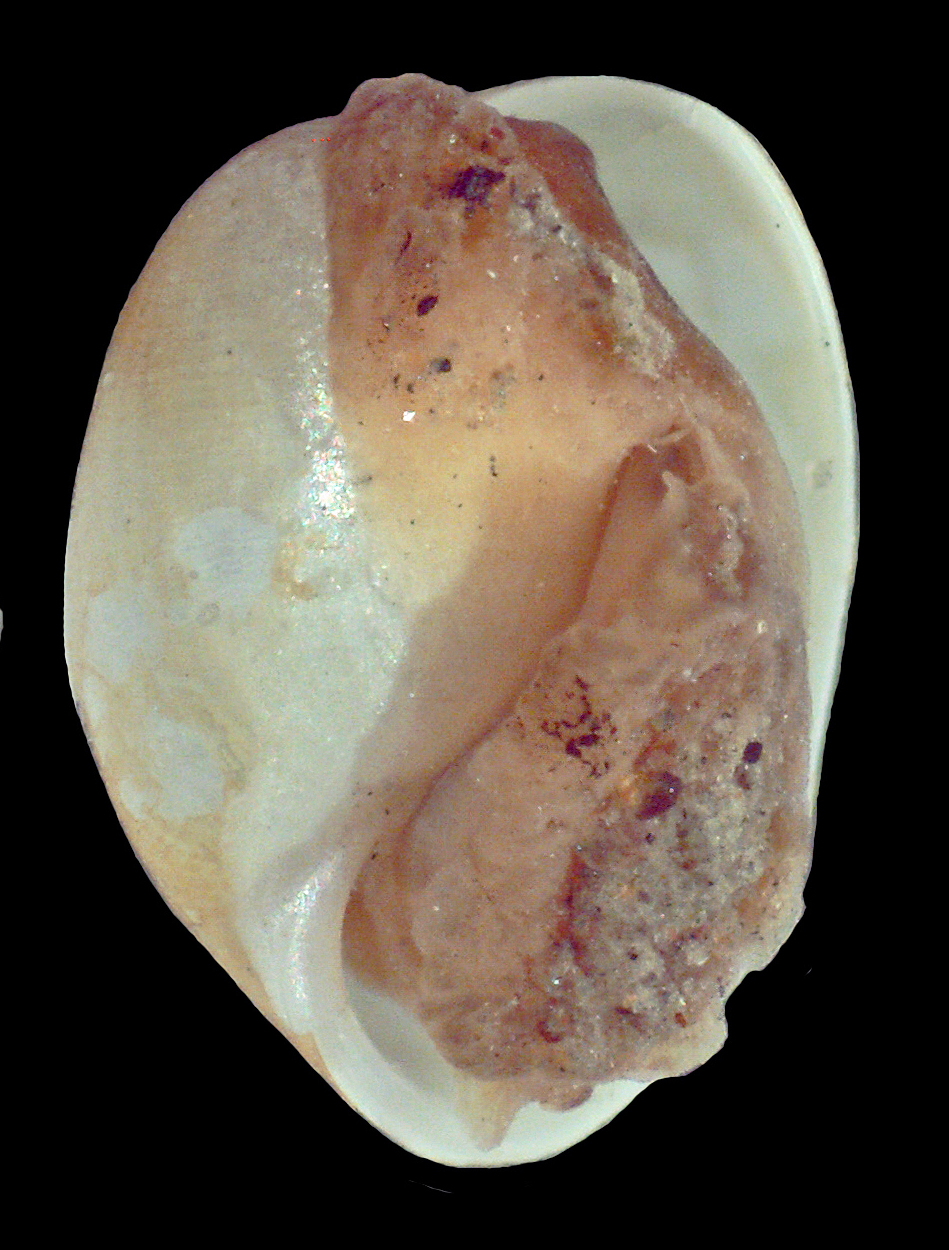

Well, this is… different. While not particularly photogenic, it is easier to see the shell opening in this preserved white bubble snail.

Bubble snails are difficult to identify in the field – the colors of their bodies and shells can vary, and often their shells are tucked out of sight. Preserved specimens tend to be more scrunched up, allowing taxonomists to closely examine their shells. This is helpful for distinguishing H. vesicula (narrow shell opening) and H. virescens (wide shell opening).

Complicating matters is the introduction of a third species that is not native to Washington’s waters: Haloa japonica, the Japanese bubble snail. Native from Japan to Hong Kong, H. japonica first appeared in the San Juan Islands in 1985 and was originally thought to be a new species. It looks very similar to the others at first glance, but unlike the native species which have shallow notches in the backs of their heads, H. japonica’s head is deeply notched, making it look like it has bunny ears.

Identical triplets? Nope, three different bubble snail species. Left: Haminoea vesicula, by Florida Museum of Natural History (FLMNH); Center: Haminoea virescens, by dmc_oceaninvertebrates; Right: Hanoa japonica, by FLMNH. All photos from iNaturalist, CC BY-NC-SA.

All this talk of bunnies and bubbles is giving me spring fever… time to get out from behind the microscope and soak up some sunshine!

Critter of the Month

Dany is a benthic taxonomist, a scientist who identifies and counts the sediment-dwelling organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see to detect changes over time and understand the health of Puget Sound.

Dany shares her discoveries by bringing us a benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.