Trick or treat?

Where the wild things are

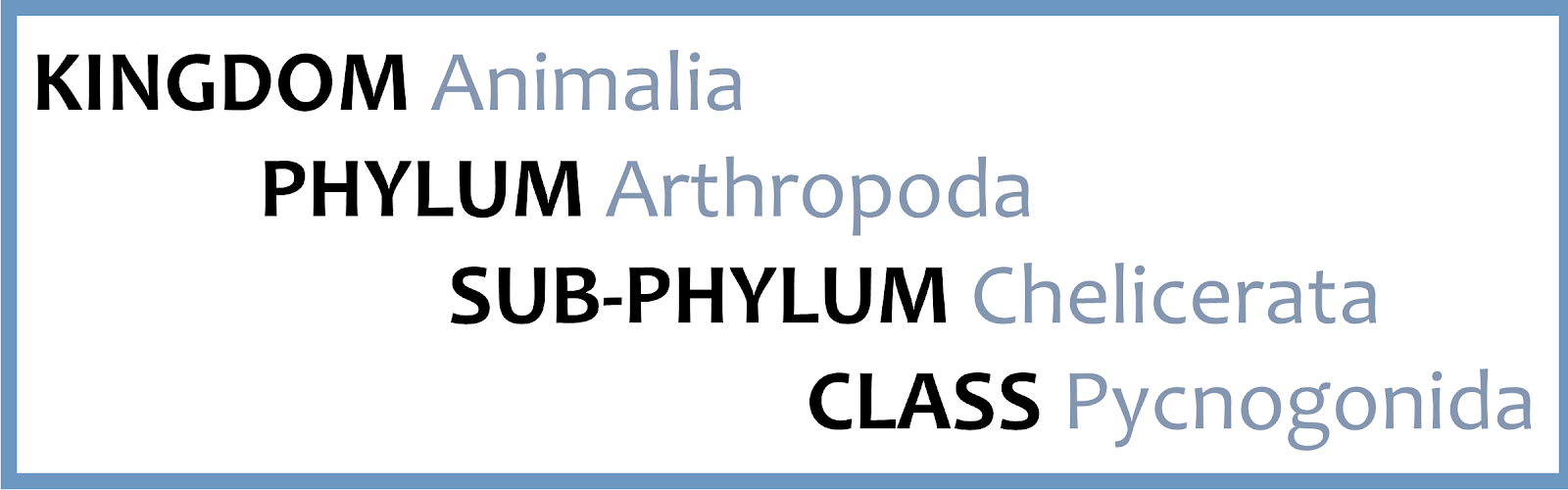

Pycnogonum stearnsi, Stearns' sea spider. Photo courtesy of Dave Cowles, wallawalla.edu

The dorsal

Don’t let the bed bugs bite

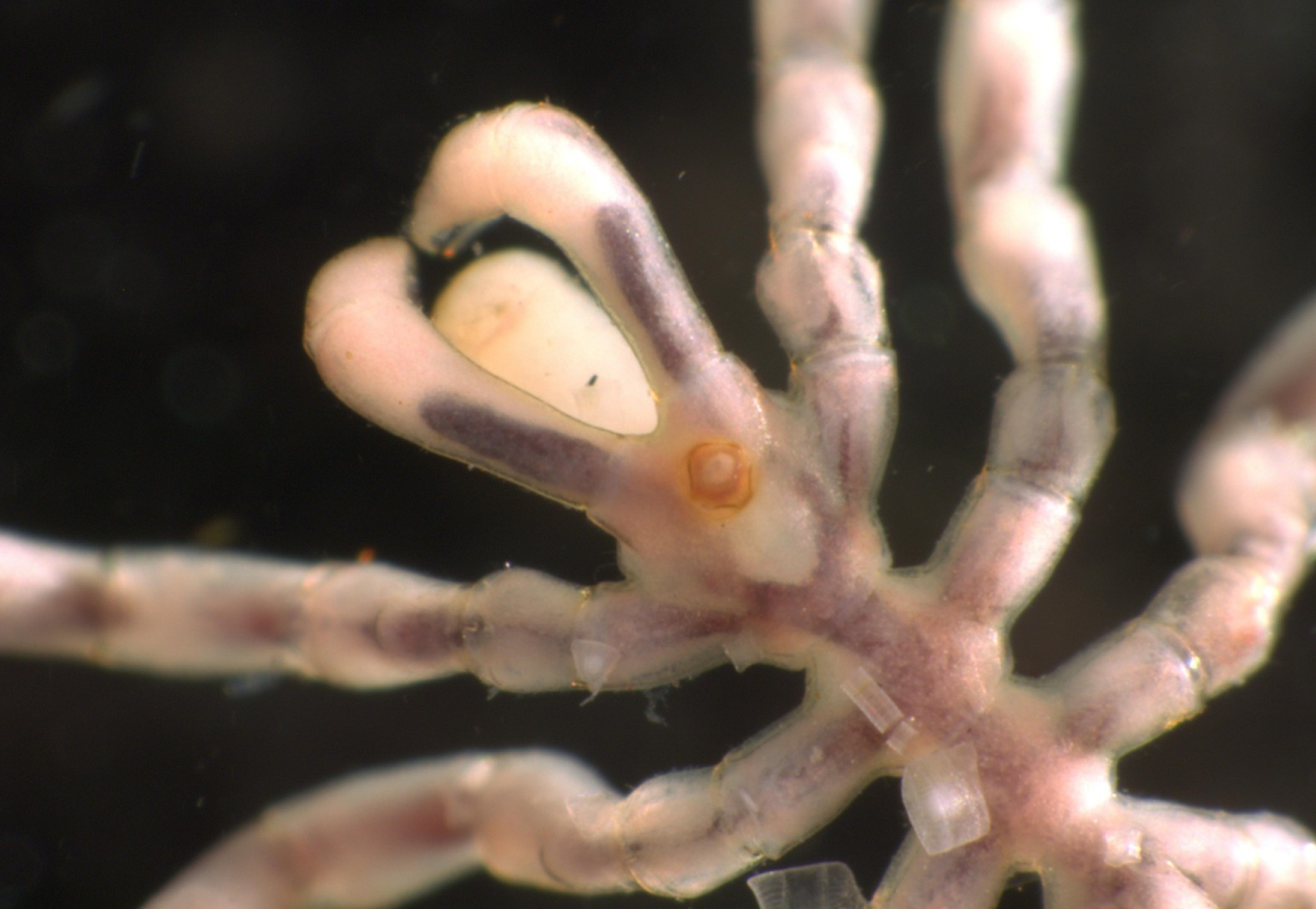

Although sea spiders might haunt the dreams of arachnophobes, they are actually harmless to humans, and lack the fur and fangs that make terrestrial spiders so scary. The sea spider’s body is small in comparison to its four to six pairs of long, prominent legs (think, daddy long legs rather than tarantula). The body is composed of two main sections: the cephalothorax (head/upper body), and the smaller abdomen (lower body region). Located on the cephalothorax is a lump called the ocular tubercle, with four simple eyes on the top. Close-up of the cephalothorax of Nymphon sp.

Sea spiders are incredibly slow, so they feed primarily on immobile prey: invertebrates such as sponges, anemones, cnidarians, and bryozoans. They also lack the complex mouthparts that most arthropods have, so they prefer soft-bodied animals, sucking the juices up through a long straw-like proboscis located on the underside of the cephalothorax. Some species also have a pair of chelifores with tiny claws for tearing off small pieces of food.

Blood and guts

There isn’t much room to spare in a sea spider’s thin body, so it’s convenient that they have no need for lungs, gills, or respiratory organs. Instead, they have magical, multifunctional legs which provide a large surface area for collecting oxygen through diffusion. Anoplodactylus viridintestinalis has a bright green digestive tract

Surprisingly enough, digestion and circulation also take place in the legs, with digestive fluid and blood flowing easily though these amazing tube-like appendages. Blood is pushed through the legs by the gut, not the heart, which is too small and weak to pump blood to the sea spider’s extremities. The sea spider is the only animal in existence to have a gut that works to pump blood - now that’s a gut-wrenching bloody good show!

Father knows best

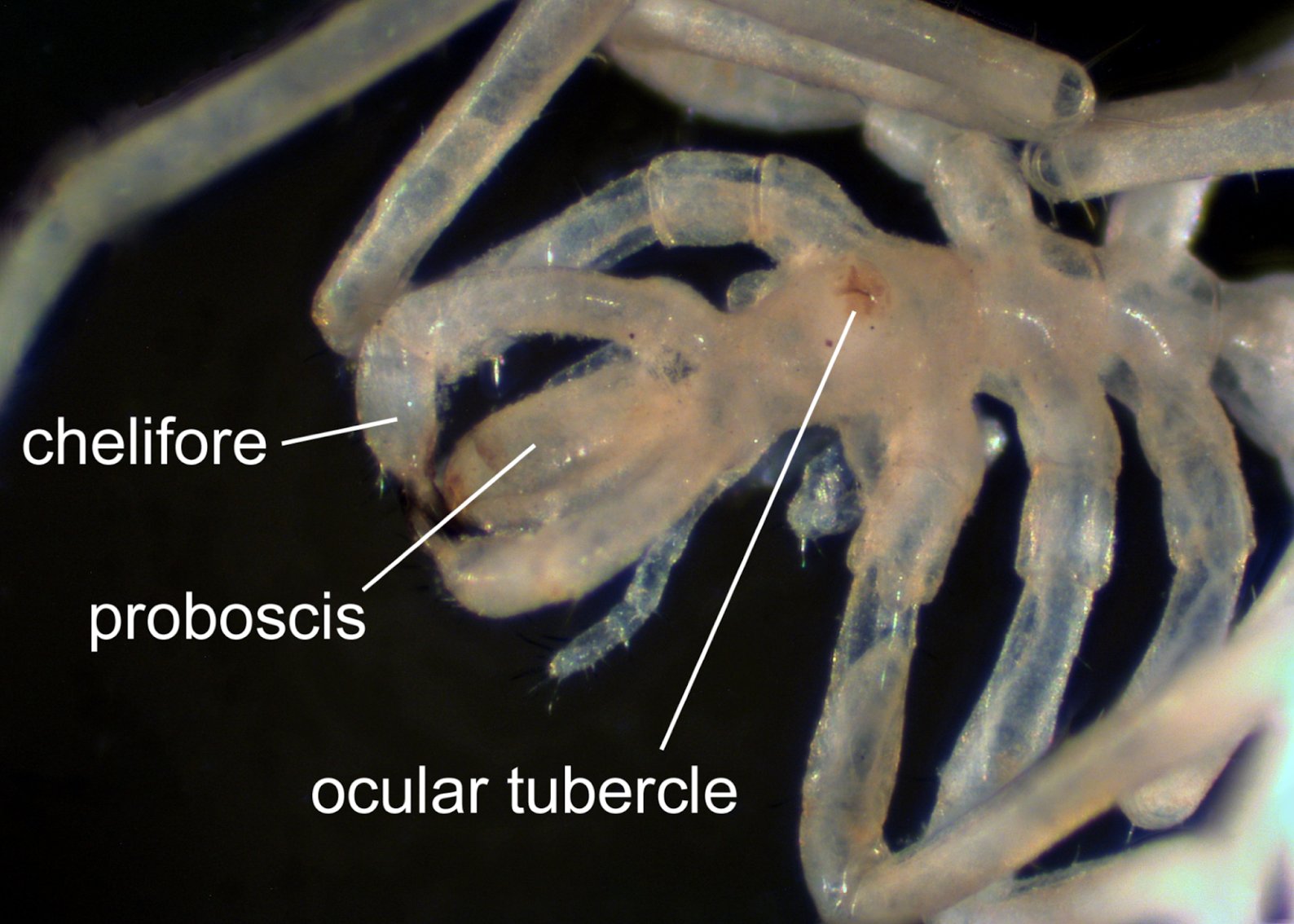

Top: Close-up of the underside of a male Nyphon sp., showing the ovigers. Bottom: A male Anoplodactylus viridintestinalis clutches egg masses.

Critter of the Month

Our benthic taxonomists, Dany and Angela, are scientists who identify and count the benthic (sediment-dwelling) organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We track the numbers and types of species we see in order to understand the health of Puget Sound and detect changes over time.

Dany and Angela share their discoveries by bringing us a Benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.