The rise of road litter

In Washington, like the rest of the nation, roads are vital to the lives of everyone who lives, works, and plays here. The 1,000 miles of interstate, when added to the network of more than 7,000 miles of state highways, give Washingtonians easy access to mountains, rivers, beaches, lakes, and people places — both urban and rural. With more people hitting the roads to their favorite recreation spot, an unfortunate phenomenon began appearing across the state — roadside litter.

Protecting, preserving, and enhancing the environment for current and future generations is the mission driving Ecology for the last 50 years. Maintaining the quality of scenic roads and the health of roadsides and what lies downgrade is a cornerstone of our work and serves as a thermometer to litter control efforts across the state.

Tackling the litter problem and changing behavior is no easy task, especially considering the history of shifting priorities and budgets, and the need to stay relevant to audiences of the time.

The litter program is born

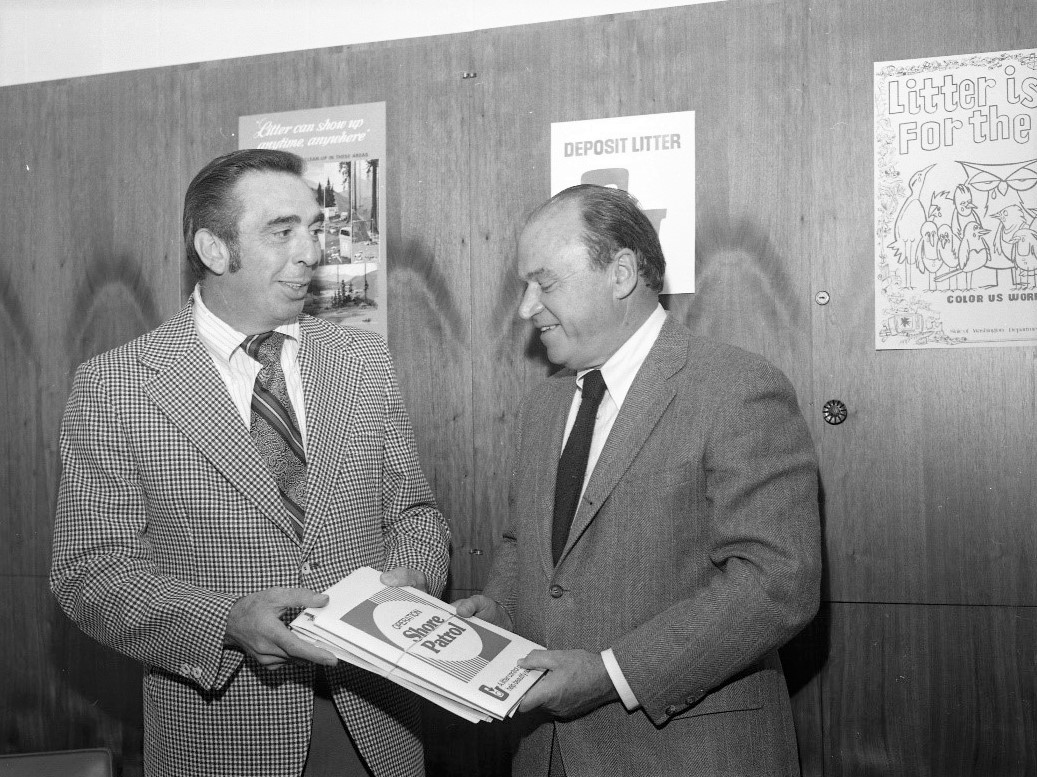

The roots of our litter program began in 1971 when a group known as “Industry for a Quality Environment” representing manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers of frequently littered consumer products initiated a self-imposed “litter tax.” The Model Litter Control Act levied a 0.015% tax on food, cigarettes, soft drinks, beer, wine, newspapers, magazines, and other items. This was an extraordinary step forward for an industry group to take, and stemmed from fear of a bottle bill, which just passed in Oregon and imposed a deposit on certain recyclables. The new law aimed to change the habits and behaviors of citizens through strong education programs. It also set fines and enforcement policies for littering, created a youth jobs program in litter pickup, required the placement of garbage cans in certain public places, and encouraged the development of small private recycling centers. Flanked by anti-litter posters, Ecology officials present "Shore Patrol" folders in 1973.

Ecology was about a year old when the Model Litter Control Act passed. The young agency was over-extended, but worked diligently to set the foundation of America’s first coordinated state environmental agency. We implemented several litter control efforts, including anti-litter campaigns and educational programs. Industry for a Quality Environment remained very engaged as a partner in Ecology’s efforts, ensuring its members were looped in and up-to-date on the impacts of state litter programs.

Litter prevention education

Educating and engaging the state’s youth was a big focus in the early years. A long-haired, bespectacled “Professor Rettil” (litter spelled backward) was the main character in a unique litter prevention curriculum provided to schools. Larry Nelson, a radio personality on KIRO Radio in Seattle, played the silly character. This week-long audio/visual presentation provided a segment a day for participating classrooms. Displays in stores and other public areas played Professor Rettil’s litter messages for the public.

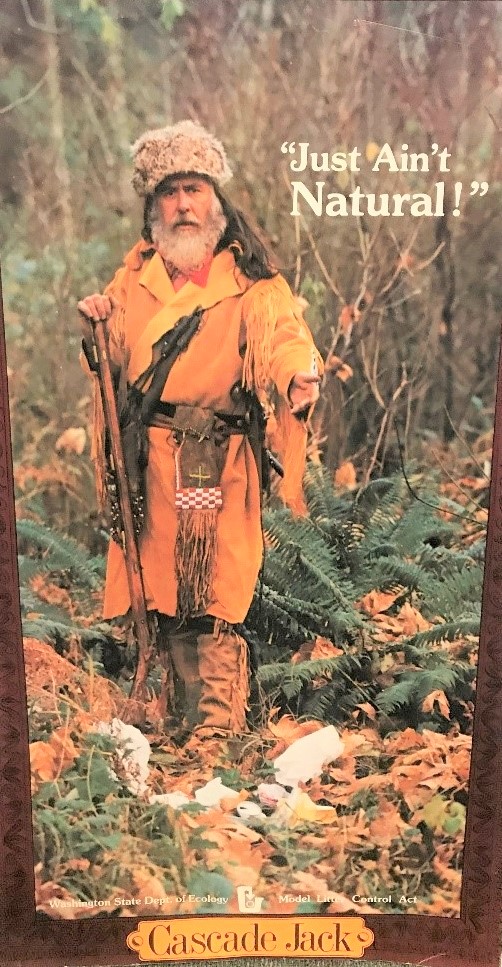

Cascade Jack: A man for the times

Cascade Jack visited schools across the state to encourage kids to help reduce litter for nine years, beginning in 1974.

"I played it with humor, particularly in the schools," said Eckerson at the time. "I would take frontier yarns, tall tales and outrageous lies, all with a humorous bent."

Former Washington governors Dan Evans and Dixie Lee Ray renewed their support for Cascade Jack’s efforts to fight litter, but the campaign ended with budget cuts in 1983. During our 20th anniversary in 1991, Ecology’s Rod Hankinson reprised the Cascade Jack role as the agency celebrated.

Over his 9-year run, Cascade Jack visited schools across the state to encourage kids to help reduce litter.

Bikes everywhere!

Jobs for teens: Ecology Youth Corps

1961 Nash Ambassador station wagon

There was tremendous support from the legislature and Ecology got the equivalent of 74 full time employees.This resulted in hiring regional litter staff and several hundred teens for the first EYC season in 1975. Vans were not available at the time, so we purchased a fleet of state surplused Nash Ambassadors.

A crew consisting of one supervisor, five kids, bags and other supplies jammed into these classy crew vehicles and took to the state’s highways. They drove the station wagon with its blinkers on, while kids walked in a line on the shoulder — no traffic warning signs, cones, or safety gear. And kids picked up litter with their bare hands.

Safety precautions evolved significantly over the ensuing years. The EYC program served dual roles picking up roadside litter and providing experiential environmental education to teens and the general public. The bright white EYC bags full of litter were strategically stacked along the roadways with logos facing oncoming traffic. The goal was to leave the mountain of bags on the roadside for a few days to make an impression on drivers and show the incredible impact of this new program, a public relations tactic that continues to pay off each spring since the program started. EYC quickly became an iconic and impactful program.

"This is the first job for many of these kids," said longtime regional EYC supervisor Rod Hankinson. "These kids are tough — this isn't an easy job. I tell them this is the kind of work that helps them throughout their life. It teaches them to respect the environment and what they can do to help it. The program also sets them up to receive recommendations from their supervisors for college and future jobs.”

Making a difference one piece of litter at a time.

Litter programs and unique partnerships

Ecology Youth Corps distributing car litter bags at a public event in 1981.

There were campaigns titled “Shoot for Zero Litter” — a program for hunters, “Pick up a Mountain” for backpackers, and “Ski Litterless” for skiers. “Shore Patrol,” in partnership with the Four Wheel Drive Association, drew a crowd of more than 5,000 people on one weekend on coastal beaches to fill up their “Department of Ecology Volunteer” litter bags. Grants to city and county governments provided full-time police officers dedicated to litter enforcement and education. These officers drove cars with a “Litter Patrol” emblem on the side. The officers would go to schools and talk to kids about enforcement of the litter and recycling laws. And a series of annual litter studies confirmed that litter decreased by 66% across the state between 1971-1976. Some view the early 1970s as the golden years of Washington’s litter efforts.

Changing times and a growing problem

A variety of patches from Ecology’s past litter programs.

In 1997, a new Litter Task Force evaluated Washington’s litter activities. The Task Force made a number of recommendations to address the growing problem. In 1998, the Legislature realigned funding and incorporated the Task Force’s recommendations as amendments to the Litter Act. With restored funding, we re-established a comprehensive litter prevention campaign.

Litter and It Will Hurt

The character’s name was Torquemada, and he used to work for the Spanish Inquisition. Television and radio commercials used humor and threat of getting caught, fined, and potentially tortured by Torquemada. A litter reporting hotline gave non-litterers an opportunity to make a difference, and signs promoting the hotline went up along roadways. Reported litterers received a special educational warning letter on State Patrol letterhead.

Litter survey and phone survey data showed the campaign successfully raised awareness, altered beliefs about the likelihood of getting caught littering, and decreased littering behavior. This resulted in a 25% decline in roadway litter in the first two years of the campaign. Taking 4 million pounds of litter off the road was a significant achievement. The Litter and It Will Hurt campaign was the most comprehensive and well-known litter prevention campaign in the state’s history.

Washington’s litter prevention efforts gained national attention during a campaign against “trucker bombs” – bottles of urine that drivers litter along roadways. The Daily Show with Jon Stewart sent Samantha Bee for a hilarious interview at a Federal Way truck stop with Megan Warfield, who led the Litter and It Will Hurt campaign. The Comedy Central episode earned Megan some notoriety. Long after it aired you could still find her name in a Google search for “urine.”

In 2009, the Legislature diverted litter funds to help balance the budget and for maintenance at state parks. The funding cut reduced the number of litter pick-up crews on the road and discontinued the prevention campaign and reporting hotline. This lack of funding for litter prevention activities remained in effect for 10 years, and the 4 million pounds of litter, and more, made its way back onto the roads.

Revived funding and new litter prevention goals

In 2019, the Legislature restored funding and provided the long-awaited opportunity to not just pick up litter, but prevent it from becoming a safety issue and eyesore. A Litter Prevention Coordinator was hired and worked to secure contracts with consultants to design and launch a multi-faceted, multi-media campaign and reporting hotline. A new website with an online litter-reporting tool, mobile app, local government toolkit, and a campaign sponsorship program were all part of the plan. Partners across the state began meeting to plan promotion and enforcement activities, and looked forward to being involved in the design of the new campaign. Everyone was optimistic that the litter program was back on track and would address the serious litter problem across the state.

In an extraordinary turn of events, a global pandemic came to Washington and the world. The COVID-19 virus hit early 2020 and had devastating economic impacts across the country. One week before signing the long-awaited litter prevention campaign contract, Gov. Jay Inslee took emergency action and froze all state hiring and contracts. Currently, the litter tax funds sit in limbo and may be used to offset the state’s unprecedented budget deficit. The safety of its crews being the top priority, we canceled our 2020 EYC summer litter crews for teens. Much of the roadside litter control responsibilities shifted to our adult litter crews, which were already hired and deployed in some areas of the state.

EYC continues to be one of the longest-running, most impactful litter programs to date, hiring more than 12,000 Washington teens. Picking up trash on the highways is no easy job, but for the teenage crew members, it offers experience, friendship, and even a little fun. Hear from members about what the job was like and what they took away from their summer work.

Ecology Youth Corps continues to be one of the longest running, most impactful litter programs to date, hiring more than 12,000 Washington teens. Picking up trash on the highways is no easy job, but for the teenage crew members, it offers experience, friendship and even a little fun. Hear from members about what the job was like and what they took away from their summer work.

While litter is a bigger problem than ever and there is a lot of uncertainty about funding, our litter crews have kept the state beautiful for generations. More than 12,000 teens have gone through the EYC program, carrying a new environmental ethic with them. Ecology’s educational campaigns, from mountain man “Cascade Jack” in the 1970s to Ecology Youth Corps’ 2019 participation in the viral #TrashTag social media challenge, have also earned a lot of credit for keeping the roadsides clean. The Model Litter Control Act was successful in many ways and its evolution continues to support local governments, state agencies, and the EYC program today, 50 years later.

Throughout 2020, we’re marking our agency’s 50th anniversary with stories on how Washington state’s commitment to environmental protection has developed, and the results that commitment has achieved.