Fall is right around the corner, and this month’s critter is a preview of the brilliant colors to come. The orange sea pen, also called the fleshy sea pen or Gurney’s sea pen, resembles a colorful autumn tree waving in the “breeze” of moving water currents.

Like its slender sea pen cousin Stylatula elongata, the orange sea pen is actually a colony of tiny animals called polyps working together to form a single organism. It starts out as one primary polyp that grows and expands to form the base (the bulbous part that anchors the animal in the sediment) and the rachis (the central stalk). As it grows, it adds more polyps, assigned to different jobs depending on their location in the colony.

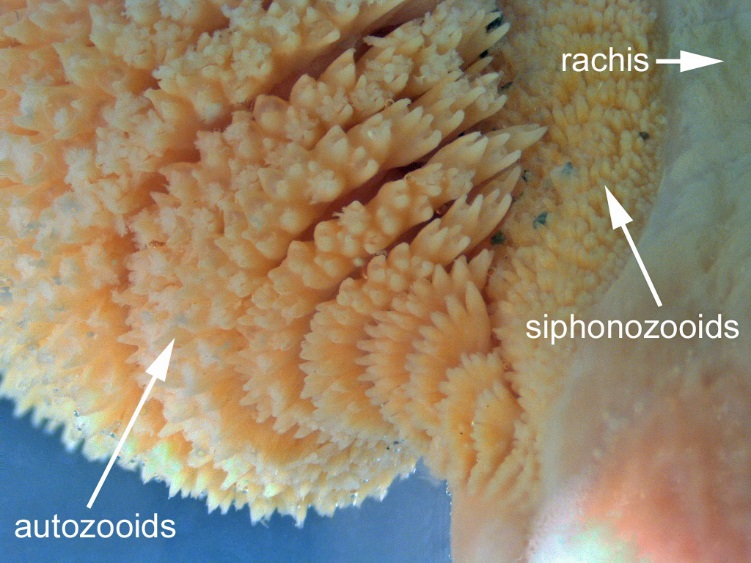

On the sea pen’s long feathery leaves are rows of autozooids: feeding polyps that wave their eight tentacles in the water to catch drifting plankton. These polyps pull double duty, also responsible for producing eggs and sperm that get released into the water column. The siphonozooids, or pumping polyps, are found in the orange regions on the sides of the rachis. Their function is to take in or expel water, allowing the colony to inflate or deflate.

Make like a tree and leave

A close-up of a preserved orange sea pen showing autozooids that are gastrozooids

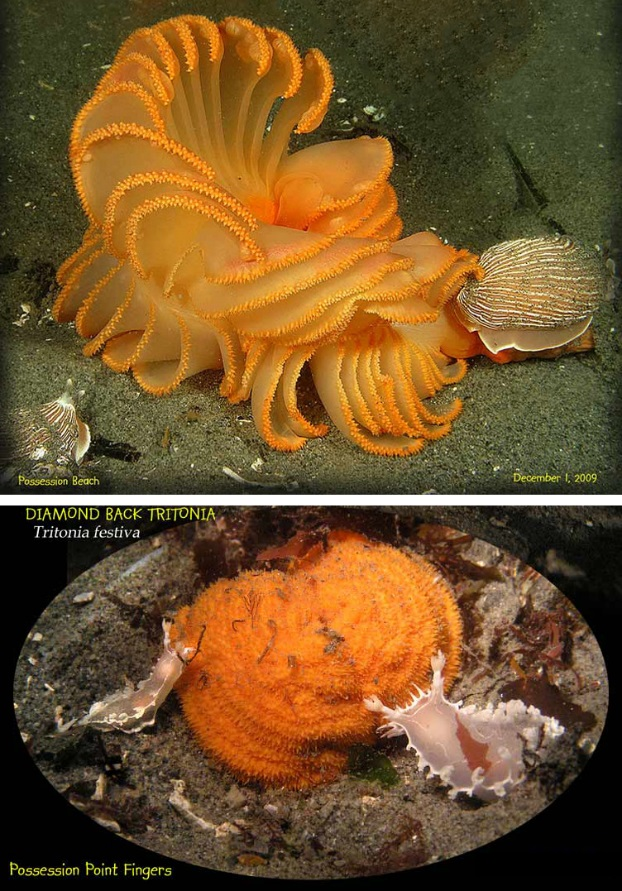

Orange sea pens make up one of the largest sources of food on the open sea floor and are important to a wide variety of benthic predators, including sea stars like the leather star, the common sun star, and at least three different nudibranch (sea slug) species.

In the limelight

Young sea pens are especially vulnerable to predation. They are incredibly slow-growing, taking over a year to reach about an inch tall. Orange sea pens increase their chances of survival with sheer numbers — a single pen can produce about a million eggs during its 10-year lifetime. Young orange sea pens, beating the odds. Photo by Jan Kocian.

Branching out

The orange sea pen may not be the only species of sea pen in Puget Sound, but it is certainly the most iconic. Its cheery form brightens up dreary sandy or muddy sea floors in shallow subtidal waters from the Gulf of Alaska to California, often occurring in dense beds with many pens per square meter.

Because of the orange sea pen’s tendency to occur in patches and in shallow water, we don’t encounter them very often in our benthic grab samples, but when we do, they are a fun and welcome sight. The adults are so easily identified that we can count, weigh, and measure them in the field and release them alive back into their environment.

Critter of the month

Our benthic taxonomists, Dany and Angela, are scientists who identify and count the benthic (sediment-dwelling) organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We are tracking the numbers and types of species we see in order to understand the health of Puget Sound and to detect any changes over time.

Dany and Angela share their discoveries by bringing us a Benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.