Water conservation is an important component to the success of the Yakima River Basin Integrated Plan. The basin, encompassing 6,155 square miles of land spread across Kittitas, Yakima, and Benton counties, has experienced decades of water conflict and concern over shifting environmental conditions.

The Integrated Plan offers a vision for protecting and enhancing the land, water, and communities in the face of drought and climate change. This semi-arid area supports a thriving agricultural economy reliant on irrigation water. Unfortunately, a fair portion of the infrastructure that distributes water is aging, outdated, or in need of repairs or upgrades. Additionally, as farms, businesses, and technology have evolved, the irrigation infrastructure has needed to evolve with it.

Modernizing delivery systems

A main goal of the water conservation element of the Integrated Plan is to improve and modernize agricultural water systems, as well as municipal water systems, to reduce waste in the form of leaks, seepage, and inefficient or imprecise delivery methods.

Water, a precious resource in high demand, cannot afford to be wasted.

Growing crops is by far the greatest use of the water in the Yakima Valley, one of the country’s most diverse agricultural producers. From asparagus in the spring to pears and wine grapes in the fall, the valley shares its bounty locally, regionally, and throughout the world.

Drip irrigation provides incredible water savings

Across the Basin, farmers have implemented conservation measures as new technologies have come available. Some projects have occurred organically, as technology advances in irrigation methods have adapted in response.

“Farmers know upgrades are inherently necessary as they carefully manage water during water short years,” said Tom Tebb, director of Ecology’s Office of Columbia River. “These investments are helping to stretch water supplies, and, at the same time, have proven beneficial for crops as well.”

For instance, flooding water along narrow furrows between hop rows and grape trellises was once a common practice. Now farmers have upgraded their systems to more precise drip irrigation that produces consistent growth and larger yields, all using less water.

Other conservation projects are much larger in scale. Kittitas Reclamation District has lined more than three miles of their North Branch Canal with concrete and a technologically advanced geo-membrane to transform a leaky earthen berm into a safer, more efficient delivery system. The district is in the process of lining 6.7 miles of the South Branch Canal as well. Projects like these are underway across the basin — all in an effort to use wisely every drop of water available.

Many are turning to completely enclosed systems. Selah-Moxee Irrigation District, for instance, has converted miles of open ditch laterals to pressurized pipelines. This reduces the volume of water diverted from river, to canal, to ditch, and field. Pressurized pipes let farmers turn water on and off with a spigot, allowing them to apply water only when needed.

Kittitas Reclamation District's South Branch canal lined with new concrete, shown partially complete here. Lining prevents loss of water through leakage.

All of these projects are expensive and benefit from shared on-farm, district, local, state, and federal funding. They take the long view to support a $4 billion agricultural industry in anticipation of hydrologic changes in climate and snowpack.

State and Federal cooperation

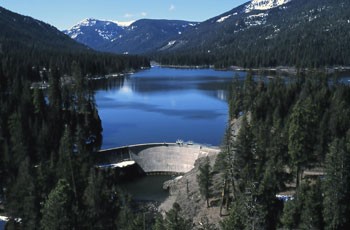

Though the roots of the Integrated Plan date back some 40 years, the current iteration of state and federal cooperation began with the passage and funding of state legislation in 2013, followed by federal legislation in 2019. The federal legislation, known as the John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, set a goal of conserving 85,000 acre-feet of water through agricultural and municipal infrastructure improvements, education, and outreach by 2029. That is the equivalent of storing water in 16 reservoirs the size of Clear Lake on Highway 12 in Yakima County.

Now, one year since the federal legislation passed and seven years since the state legislation, we are tabulating the multitude of water conservation projects funded under the Integrated Plan, and determining how far we have come to meeting the 2029 goal.

The initial development phase aims to conserve nearly 16 times the quantity of water held behind the Clear Creek Dam.

Counting up water savings

To make an accounting of what projects have occurred, we've had conversations with our partners in the Yakama Nation, the US Bureau of Reclamation, irrigation districts, conservation districts, cities, counties, and other involved organizations. So far, the partners have implemented 70 conservation and water efficiency projects in the last seven years. With approximately $67 million of state, federal, and farmer money invested, these projects have yielded over 36,000 acre-feet of conserved water. That breaks down to approximately $1,900 per acre-foot of water. The water savings support streamflows to aid fish and riparian habitat, and provide drought resiliency for irrigators. Some conserved water will allow the Wapato Irrigation Project to provide additional irrigation on tribal land.

With these projects, we've been able to accomplish approximately 42% of the plan’s first phase conservation goal. We are optimistically looking forward, as virtually all the parties involved are moving ahead with plans for future conservation projects. A strategy is underway to prioritize projects to achieve the 2029 goal and make the basin irrigation systems as efficient as possible.

We anticipate technological advances will continue to evolve and increase conservation effectiveness in the future. It's a challenge, but one that is being taken on with eagerness and enthusiasm.

Extensive piping has reduced impacts to Manastash Creek, allowing streamflows to support returning fish. Previously, the creek ran dry due to irrigation diversions.