It’s the time of year when people start wondering whether we can expect a drought in the near future. After multiple droughts over the last several years the question “will there be water” is likely on a lot of people’s minds. For most of the state, we’re cautiously optimistic. A few areas may see some challenges.

Snowpack

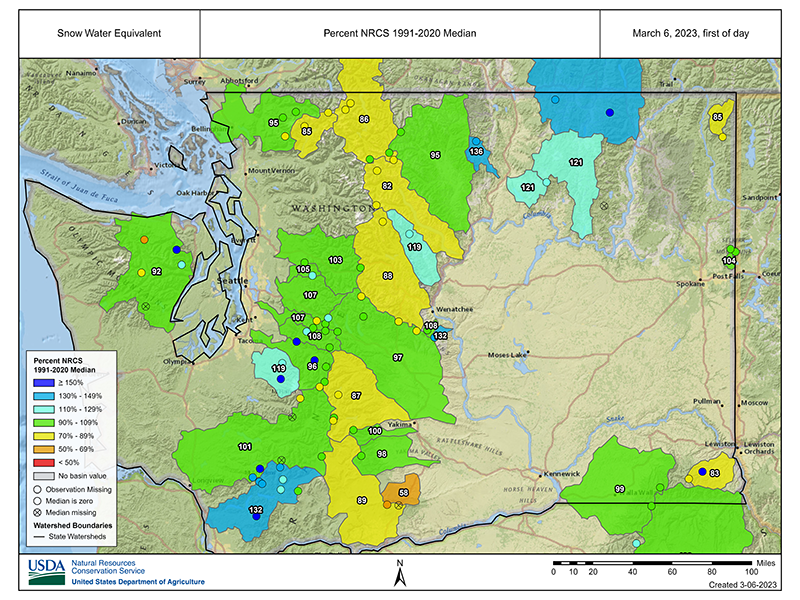

You’ll often hear a lot of talk about snowpack, or the lack thereof, when discussing water supply. Many watersheds in Washington, such as the Wenatchee and Methow River Basins, depend heavily on snowpack from the Cascade Mountains. During the spring and summer months, melting snow runs off into streams. A weak snowpack in the winter can result in low streamflows in the spring and summer. Even a healthy snowpack can dry up quickly if the spring and summer are unseasonably warm.

Right now, statewide, snowpack is slightly above 100 percent of normal, with runoff statewide forecasted to be just shy of average. Some basins are a little higher or lower than average. Lurking beneath the snowpack are soil-moisture deficits resulting from a dry spring and summer. Soil-moisture conditions are causing runoff forecasts to be revised downward in some basins, especially in the Okanogan and Methow basins.

Precipitation

Most people naturally associate drought with extended dry spells. In Washington, the official drought criteria also consider factors like snowpack conditions, and whether those conditions will cause water supply hardships. This means that in a watershed with robust storage, such as Seattle or Tacoma, lack of rain may not mean drought.

Washington state receives most of its precipitation during the winter months, and dry winters can lead to lower water levels and drought conditions in the summer.

Statewide, this winter saw a split in precipitation between the eastern and western halves of the state. The west side was drier than normal. The east side was wetter. Averaged statewide, January was the 27th driest on record since 1895. February saw 75 percent of normal precipitation statewide and was the 31st driest February on record.

La Nina conditions that ended March should have given us a wetter winter than they did. But our winter precipitation (December – February) came up somewhat short, at 86 percent of normal.

Below-normal rainfall this winter also has caused reservoir refill to lag a bit. Junior water users in the Yakima Basin, specifically the Roza and Kittitas reclamation districts, can expect to receive only 86 percent of their usual entitlement.

Temperature

High temperatures can increase the rate of evaporation and reduce water availability, particularly in areas where there is limited groundwater or surface water. High winter temperatures mean water typically stored as snow will run off in earlier than usual, at the expense of late-summer streamflow. January temperatures were slightly above normal, but February ranked the 51st coldest since 1895 ( -1.9°F below the 1991–2020 mean).

Resources

There are numerous resources available to check on water supplies and drought condition.

The U.S. Drought Monitor keeps a map of Washington updated weekly. The Natural Resources Conservation Service maps the snow-water equivalent in basins throughout the state. The Northwest River Forecast Center provides runoff forecasts for rivers throughout the northwest.

It's important to note that, while the state of our snowpack is a helpful clue of things to come, springtime and summer precipitation play a big role as well, and forecasts can change based on a variety of factors. As a result, it's important for communities and water managers to remain vigilant and prepared for drought conditions, regardless of any predictions we might make.

2022 Pacific Northwest Water Year Impacts Assessment

This is the third annual assessment.