Mount Rainier from Pigtail Peak on Feb. 18, 2022. Photo by Chris Lynch, USBR

Since Jan. 1, Washington’s weather and water supply has been on a bit of a seesaw. A large snowstorm early in the month “packed” the snow up in the mountains and even drifted into the foothills and plains of Puget Sound.

Later in the month and largely through February, we saw no significant rain or snow. There was a cold blast just after the President’s Day weekend — even garnering a few record lows (8-degrees at the Yakima Airport on Feb. 23). However, the snowflakes accompanying it were not robust enough to last. At least, that cold air helped keep in place the snowpack we already have. However, the lack of snow in February and a dry spring could be a bad sign for the snowpack we so rely on throughout the state to supply water for people, farms, fish, and recreational pursuits like skiing and snowmobiling.

The return of rains to the state in the last couple days has created flooding potential at multiple locations on the west side and on the Yakima River. This can lead to “drought messaging” challenges since it’s hard to think of drought during a rainy spell. But there are still snow deficits on the east side.

So at this point on the calendar, the year 2022 is giving us “cause for pause” and keeping our water resources managers on alert.

Snow measurement reads at 7 feet at Pigtail Peak on Feb. 18, 2022. Photo by Chris Lynch, USBR

That sense of urgency comes from last year’s “Water Year of Surprises,” when a historically dry spring, capped off with a record heat dome in June obliterated a huge snowpack, resulting in a nearly statewide drought declaration that remains in effect today.

“That carryover drought declaration is part of a strategy,” said Jeff Marti, Ecology’s statewide drought coordinator. “Planning for the possibility we might not be fully out of drought conditions come the following spring. And for parts of the state that’s where we find ourselves today.”

Early March is when water supply managers start getting clarity on water supply conditions for the coming summer. “We know how much snowpack we have to work with and snowpack is the key driver of the water supply,” Marti said. “Not that there isn’t room for yet more surprises. Springtime precipitation also plays a big role in setting up the summer months.”

A wet spring can go a long way toward making up for a dry winter. Only time will tell.

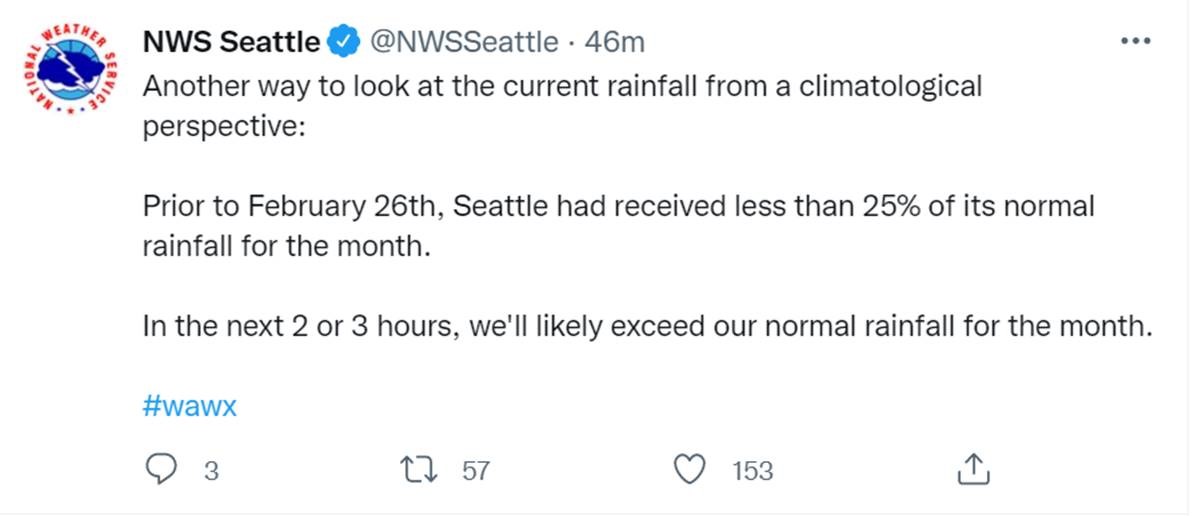

National Weather Service tweet explains current rain in terms of "climatology"

Conditions as they stand now

Scanning across the state shows the situation as follows:

Olympic Peninsula

The west slope of the Cascades has near-normal to normal conditions with snowpack ranging from 90 to 100% of normal. The Puyallup Basin leads the way for snowpack this year. The cities of Seattle and Tacoma say they have sufficient supplies for people and fish this winter.

Over in the Olympic Mountains, however, snowpack is at 83% of normal. This may be a concern for the Dungeness, where they are working to solve long-term impacts of low flows.

A new drinking water well in Forks — paid for with emergency drought funding — should make the town more resilient to low groundwater levels during drought years. In Neah Bay, folks often go on voluntary conservation during dry summers.

Southwest Washington

In some Washington watersheds, rain rather than snow is the predominant driver of water supplies. Forecasted runoff is 85% of normal in the Chehalis Basin despite current flooding. An extended period without rain this spring could result in restrictions on water use for junior irrigators. Such curtailments are becoming a norm and prompting urgency for water solutions through the Chehalis Basin Strategy.

Cities like Vancouver rely on the plentiful Troutdale Aquifer, which is less impacted by low streamflows or low precipitation.

Eastern Washington

In much of Eastern Washington, irrigators rely on the Columbia River to water the crops that support the state’s $11 billion agricultural economy.

The Columbia River has its headwaters in the high elevation areas of the Cascades, Northern Rockies and Canadian Rockies. Snowpack in the Canadian Rockies is well above normal. Estimated forecasted April to September runoff for the Columbia River measured at the Dalles Dam is 96% of normal, meaning irrigators who take water from the Columbia River will have adequate supplies this summer.

Last year, Washington’s dryland farmers suffered the most because they are at the mercy of recent precipitation patterns. If conditions continue to be dry, crops may be stressed and yields reduced. Lower availability of natural forage and poorer pasture conditions may force livestock producers to again search for alternative sources of feed to support their animals.

Near Spokane, the forecast for the Little Spokane River is for less summer runoff than was even observed last summer. This means irrigators with junior water rights are likely to face water shutoffs this summer, as they were last summer.

Walla Walla River at Touchet in August 2021

Southeast Washington

The Walla Walla River, a smaller tributary to the Columbia — but one that supports critical agriculture — is facing a more challenging summer with forecasted runoff below the state drought threshold. In dry years, senior water holders will put out “calls” for water earlier than in wet years. This means that state watermasters will be asking junior water holders to turn off their own diversions earlier than usual.

Central Washington

Central Washington is a region that relies on snowpack to water crops, recharge groundwater, and support important salmon runs in the Yakima, Wenatchee, Okanogan, and Methow river basins. And it’s an area where Mother Nature has thrown more than a few curve balls in recent years.

The Bureau of Reclamation, which operates the series of reservoirs and dams collectively known as the Yakima Project, will be sharing an official water supply forecast on March 3. Currently, total system storage is approximately 125% of normal thanks to a wet fall. But snowpack — the other major form of water storage — is much below normal. There is question whether the amount of artificial storage will be enough to compensate for the reduced amount of “natural” storage in the form of snowpack.

In the Okanogan, snowpack at the Conconully is lagging, as are projections at Stampede Pass, another place we will be watching this spring.

Statewide condition resources

As the season proceeds, we’ll be monitoring watersheds and providing updates. Some areas may no longer fall into our drought thresholds, while others may stay there as we enter the growing season.

Many resources are available to help water users learn about and understand conditions throughout the state. We update our Statewide conditions page monthly with a brief summary of precipitation and a link to the most current issue of the State Climatologist’s Newsletter. You can find current data about streamflow, snowpack, precipitation and more on our Water Supply Monitoring page.

Our Drought 2021 page (yes, it’s still the same drought) features information about the current drought and links to resources, including the new 2021 Pacific Northwest Water Year Impacts Assessment. Lastly, you can learn about Ecology responds to drought on our Drought preparedness and response page.