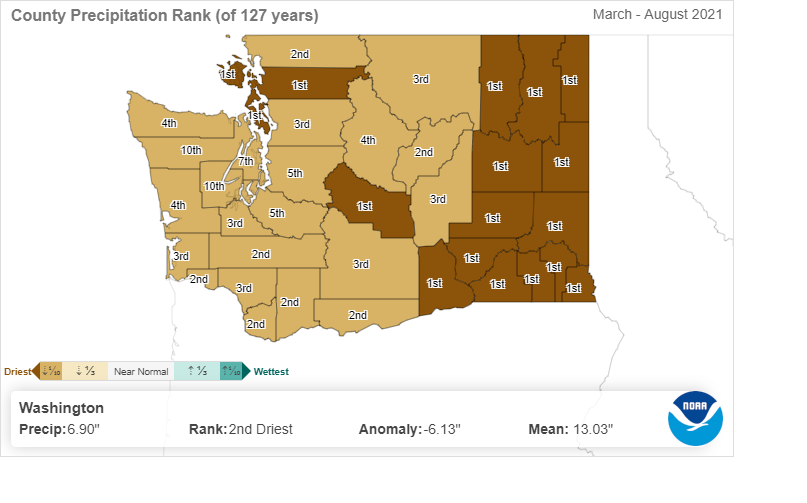

Many Eastern Washington counties recorded the fewest inches of preciptation from March to August since 1895 when records began. Other counties are also recording extremely dry conditions over the past 127 years.

When water managers talk about the water year, they describe it beginning in October and ending in September. The irrigation is done, and the harvest complete.

By October we expect rain or even snow… and the fires to go out… and the planting of winter wheat and new trees, anticipating regrowth in spring.

Over winter, snow piles up in the mountains, creating a cushion that slowly melts to irrigate and nourish crops, provide passageway for migrating salmon in creeks and streams, and recreational opportunities for people on lakes and rivers. Rain and snowmelt recharge our aquifers, and support our rainforests, and communities both east and west.

In the big picture, snowpack generates power for the entire region at dams on the Columbia River. It creates a corridor for container ships making ports of call at Portland below the major dams and barges moving cargo and crops to and from Clarkston through the Snake River.

All in a “normal” water year.

Anything but normal

Yet here we are in September, despite recent rain, looking at conditions that are some of the driest in recorded history!

In April, a huge reserve of water, stored in the form of snow in the high Cascades, measured in at a whopping average of 132 percent of normal, statewide. It appeared we were set.

Now wildfires still smolder. And now as many as 16 Washington counties are drier than they’ve ever been, since data was first tracked in 1895.

How did this happen in a year that began with such promise?

Let's look back a bit, and consider what may lie ahead.

But first a few statistics

According to the Weather Service (NOAA), overall from March to August, our state saw 6.90-inches of precipitation. Normal during that timeframe is 13.03 inches – a more than a 6 inch deficit, making the statewide water year the second driest in history.

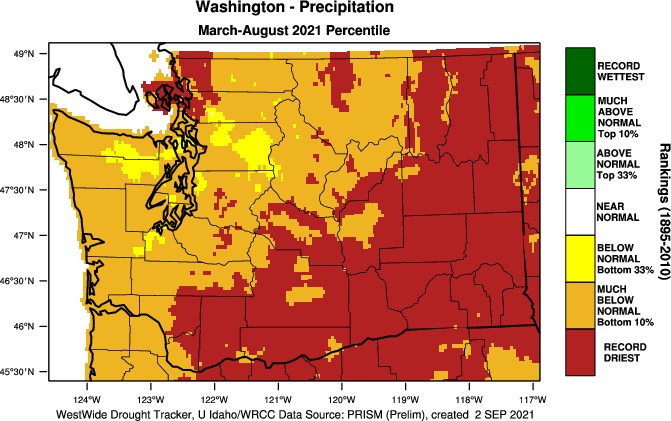

Also, from March to August, nearly three quarters of the state experienced record dryness and the other quarter was “much below normal,” that is, in the bottom 10 percent. Not a pretty picture even for the rainiest parts of Washington.

For example, to end the current drought in the lower Columbia River area, Ecology Drought Coordinator Jeff Marti notes that we'd need 11 inches of rain by next April. The odds of that kind of rebound are low and has only happened fewer than 5 times over the last 120 years.

“The question is, will we have a full recovery before next spring?” Marti said. “The odds for significant improvement of conditions are pretty good for Western Washington. But I’m less optimistic about the east side. Based on historic climatology, the odds for significantly ameliorating current conditions is about 1 in 5 across Eastern Washington. For a full recovery in Eastern Washington, the odds are about 1 in 20.”

Reviewing the data and analyzing the odds help us to anticipate conditions and provide assistance where we can. This year the snowmelt captured in storage protected the irrigated farmer, but there wasn’t enough precipitation held in the loamy soil for the dryland farmer. So there’s lots to watch in the months to come.

Will La Niña winter provide relief?

While a La Niña forecast increases the odds of a wetter winter, it doesn’t guarantee it, Marti said. "And even a good La Niña could leave areas of lingering deficits, so people need to be vigilant," he added. "Remember, last winter was a La Niña winter as well.”

This may be sobering, but we want to lay out what we know to try to help farmers, legislators, water managers and others to make the best decisions for what they need. “We can’t tell people what will happen, but we can at least share what we know about probabilities.”

Putting a fine point on the unexpected, Marti noted that on Aug. 26 the Nooksack River in Whatcom County experienced record low flows — this in a basin where snowpack was 120 percent of normal.

“Back in April, looking at our awesome snowpack, I certainly wouldn’t have expected that this year the Nooksack would be establishing some record day-of-year lows” he said. “You never can turn your back and relax because things can deteriorate.”

Taking the present into consideration

Nearly zero precipitation in spring, and a heat wave doming the state early in summer, led to rapid runoff from melting snow. The watersheds with storage, particularly the Yakima River Basin and the Columbia mainstem, have largely been unscathed. Still, soil is parched, and water stored in reservoirs is low.

For those areas where precipitation has been nil, and where they lack irrigation, it has been particularly difficult. Washington wheat, lentil, chickpeas, and potatoes are a huge trading commodity — in the billions of dollars. Federal drought emergency assistance is on the way for many, but that doesn’t provide comfort for next year.

“We’re still on the clock,” Marti said, as we look to the end of one water year and anticipate another.

In fact, this year’s drought emergency declaration extends through to next June. We still have time to act and bolster our programs before next spring. We'll be keeping the legislature, farmers, fish managers, communities and others apprised so everyone can plan as best they can.

And while this news appears gloomy, it adds to the urgency for integrated water management approaches to shore up water supplies for drought resiliency and response to climate. Work we are undertaking across Washington from the Dungeness to the Walla Walla, Nooksack to Yakima and everyplace in between

See the updated water conditions report at ecology.wa.gov/statewide-conditions.