Floodwaters carry an immediate horror — swamped homes, broken livelihoods, washed out roads — but anxiety lingers like a new high-water mark long after the rivers recede.

In early February, intense rainfall brought the biggest disaster in decades to Southeast Washington and Northeast Oregon. The Walla Walla River experienced a 100-year flood, which carries a 1% chance of happening in any given year. Mill Creek flowed at more than 7,000 cubic feet per second, the highest recorded in 76 years and nearly 70 times its normal flow rate for this time of year. Throughout the region, swollen waterways swamped levies and chiseled new stream channels.

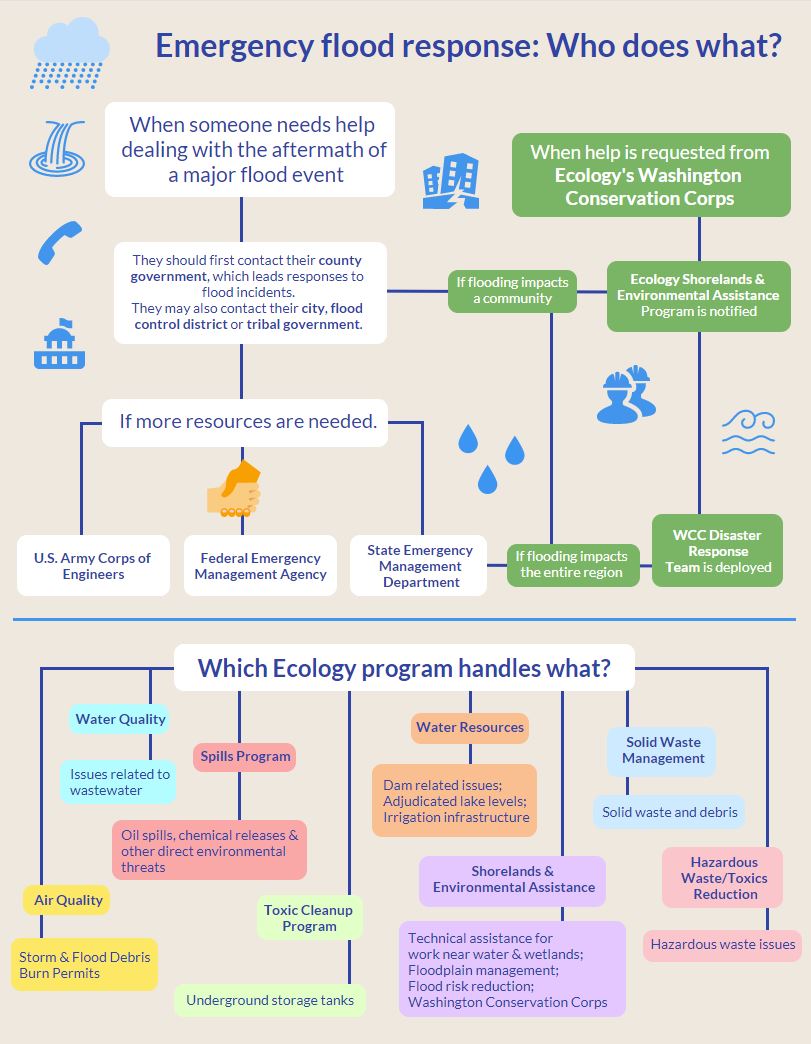

In Washington, floods like these trigger a series of reactions. Typically, elected city and county officials are first to declare a local disaster, which activates a county’s emergency services center. During major floods such as those that occurred last month, the Governor issues an emergency proclamation that directs state agencies to do everything reasonably possible to assist affected communities.

Ecology was among dozens of agencies and organizations called upon to help Southeast Washington communities regain their footing.

Direct response

When flood dangers are imminent, our safety inspectors reach out to dam owners or visit the structures themselves to ensure conditions are being watched closely and an emergency action plan is ready to execute. We regulate more than 1,100 dams in Washington and have rigorous procedures in place to protect people and property located downstream. Ecology's Washington Conservation Corps led volunteer teams to assess damage, clear debris, and strip inundated homes of waterlogged material after Walla Walla area floods.

Our Washington Conservation Corps (WCC) members and supervisors are stationed across the state to restore critical habitat, build trails, and respond to local disasters including floods. In the Walla Walla area, city and county emergency management officials requested WCC assistance. Crews led volunteer teams for several weeks after the floods, helping to assess damage, clear downed trees and other debris, and strip inundated homes of waterlogged material.

Flooding might also mobilize our environmental emergency responders to respond to reports of oil spills, hazardous material releases, or unknown containers left stranded after flood waters recede.

Many hands

Aside from direct response, we may be involved before, during, and after major floods in several ways.

We can help monitor underground storage tanks inundated by flood waters. We can also ensure businesses properly handle and dispose of dangerous materials left behind in the aftermath. And when floods claim livestock, we can lend our expertise to make sure the remains are properly disposed of and don’t pose a threat to human health or the environment.

Aside from direct response, Ecology may be involved before, during, and after major floods in several ways. See text version.

After a flood, we may process applications from water right holders and irrigation districts seeking to temporarily relocate surface water diversions while damaged intakes are repaired. We’ve been actively offering assistance to farmers and other water users affected by recent flooding.

And as farmers and other landowners deal with flood debris, we can issue special permits to local governments allowing them to burn natural materials like leaves and branches.

Walla Walla County received a permit through June 30, and the Eastern Region Smoke Management Team is working closely with fire districts and county officials to limit air quality impacts. They’re also promoting alternatives to burning, such as chipping material or cutting it for firewood.

Reducing risks

Ecology is directly involved in helping communities reduce flood risks and restore how river floodplains naturally function. Since the February flooding, we’ve been meeting with representatives from affected city and county governments as well as other agencies and organizations to discuss flood recovery and provide technical assistance.

In Southeast Washington, we’re working to establish where stream and river channels have carved new paths. Accurately mapping zones where river channels migrate in a floodplain helps communities lessen the danger of future flooding. It’s also smart financial planning, since cleaning up after a flood costs three times more than preventing damage in the first place.

While we do have funding to help local jurisdictions with emergency flood damage prevention, it’s not much. In Walla Walla and Columbia counties, we’ll spend about $100,000 to repair damaged levees and remove debris. Early estimates show damages to public infrastructure and crop loss will top $30 million.

Beverly Road near the Walla Walla River. Early estimates show damages to public infrastructure and crop loss will top $30 million.

Prevention is the best defense

Past approaches to flooding in the Walla Walla River basin and other areas focused on controlling rivers and capturing natural floodplains for property development. Restricted waterways push energy downstream, decimating salmon runs and leaving more towns and farmland in the path of dangerous floods.

In Washington, the chance that 10 or more floods will happen on any given year is greater than 80%, a likelihood that will only increase with climate change. This is why we’re working with communities to identify flood hazards, plan a more flood-resilient landscape, and complete projects that diminish the impact of future flooding.

Much of this is being done through Floodplains by Design (FbD), a program co-managed with The Nature Conservancy and Puget Sound Partnership to re-establish floodplain functions in Washington’s major river corridors. By creating partnerships with tribal governments, non-profit entities, and landowners, the program is protecting thousands of residences, farms, and businesses at risk from catastrophic flooding.

One example? A FbD project on the North Fork Touchet River protected homes from the recent flooding with a setback levee and improved habitat through floodplain reconnection, the result of a partnership with the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Salmon Recovery Funding Board, and Bonneville Power Administration.

It’s been four weeks since rainfall and rapid snowmelt saturated Southeast Washington. Progress is underway, but a full recovery is still many months out and residents will need to adapt to a new floodplain landscape. As we help these communities rebuild, we’re working to improve their resiliency to future floods so that they might come out stronger and prevent a repeat of recent history.